One of the most exciting things about widespread access to 3D printing is how it has started to push cultural institutions to begin digitizing their 3D collections. Now, in addition to being able to see free high quality 2D scans of paintings like a 15th Century Italian Pentecost and 18th Century Japanese Woodcuts, you can see (and sometimes download, print, and modify) high quality 3D scans of the Cooper Hewitt Mansion, Abraham Lincoln’s face, and Musette the Maltese Dog. With objects reaching back thousands of years scattered across cultural institutions around the world, it isn’t hard to imagine a future where the world’s cultural heritage objects are available to anyone with a 3D printer (or, say, a Shapeways account).

We’ve been able to access high quality 2D world heritage items online for years. (Image from the J. Paul Getty Museum Open Content Program, which is awesome).

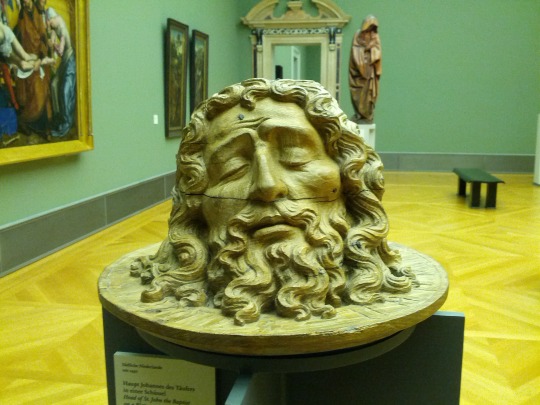

Why not high quality scans of 3D objects? (image courtesy MetMuseum)

But a question about copyright is lurking in the background of this glorious future. Specifically, a question about copyrights in the scans of the objects themselves: are 3D scans protected by copyright? If the answer is yes, scanning could drag parts of cultural heritage objects away from their home in the public domain and lock them up behind proprietary walls for decades. That would make it much harder for people to access their own cultural heritage.

Fortunately, at least one court in the United States has found that scanning an object does not create a new copyright in the scan. That means that scanning a 9th century Hanuman mask doesn’t wrap the scan in a new copyright. However, a paper from earlier this year by Thomas Margoni illustrates that the copyright status of scans is not as clear in the European Union. That lack of clarity alone could slow the dissemination of objects housed in Europe’s finest cultural institutions. Hopefully, the EU will move to clarify that 3D scans of objects do not create entirely new layers of copyright protection.

Remember, in this context we are not talking about copyrights in the objects themselves. For the sake of simplicity, let’s just focus on the thousands of years of cultural production prior to around 1920 that is well in the public domain. In these cases we are talking about someone who did not create the original object scanning it and then claiming a new copyright on the scan – and only the scan – itself.

Background: Originality

Originality is a key to understanding why a scan should or should not be protected by copyright. Originality is a general requirement to obtain copyright protection, although the bar for what qualifies as “original” is famously low. That being said, while the bar is low it does exist.

It takes a lot of work to put together the phone book. That doesn’t mean it is protected by copyright. (image credit: flickr user James Cape)

Note that in this context originality is not synonymous with “complicated” or “labor intensive.” Instead, it suggests that the author of the work made creative choices about how to create the work. In a famous US case, the Supreme Court denied copyright protection for the phone book. The court acknowledged that putting together a phone book takes lots of time, effort, and resources. But it denied copyright protection because there isn’t room for creative expression in how you assemble a phone book. The form pretty much dictates that you list everyone in alphabetical order and that each entry starts with a name and ends with a phone number. Given a pool of names and phone numbers, everyone’s phone book is going to look pretty much the same.

The same type of theory can be applied to scanning. It can take a lot of work and technical expertise to accurately scan a 3D object. But at the end of the day, the goal is to create as accurate a scan as possible. Some people may be better or worse at achieving that goal, but the nature of the task does not leave a lot of room for creative interpretation. Without creative interpretation there is no copyright protection.

That distinction is reasonably straightforward in the US. However, Margoni’s paper highlights that fact that it is not as clear in the EU. EU-wide laws designed to harmonize copyright leaves the test for originality up to each member state, and those member states have each structured that test slightly differently. That means that at least some types of scanning in some EU member countries could be protected by an additional copyright.

Why This Matters

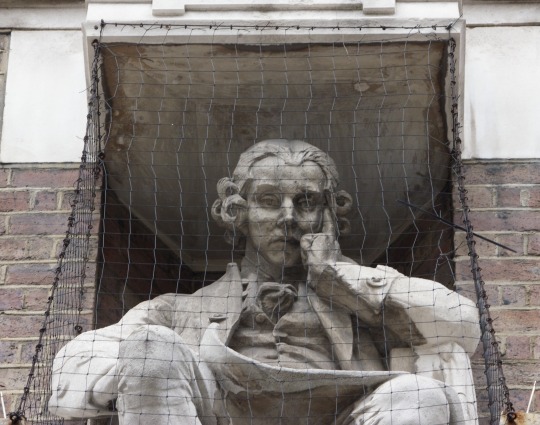

Everyone is sad when cultural heritage objects are locked up. (image credit: flickr user Ania Mendrek)

It would be bad to protect 3D scans with a new copyright because it adds another wall of rights around the object being scanned. This is especially harmful in the context of scans of world heritage objects. World heritage objects are part of our collective inheritance. Adding additional rightsholders creates a barrier for everyone who wants to access that inheritance.

Beyond copyright’s capacity to simply block use, additional layers of protection also undermine confidence in use.

Copyright lasts for a long time, and copyright rules can make it hard to determine the protection status of a given object. But, at a minimum, a statue from 1900 – or 1900 BC – is clearly in the public domain. “Made by a civilization unfamiliar with electricity = public domain” is a rule of thumb that everyone should be able to rely on without consulting a copyright attorney. If there is the potential for an additional scanning copyright, every time you came into contact with a 3D scan of a world heritage object you would have to ask a host of questions: Who made this actual scan? How did they decide to license it? Will I have to worry about someone who made a different scan suing me for copyright infringement? Regardless of the answer, the mere existence of each of these questions make it less likely that people will make use of the scans.

World heritage objects belong to everyone. There are already plenty of people trying to pull them into an ownership box without adding an additional layer of copyright protection to scans. There is no reason to make it more likely that one person will have a veto over how these objects are used. The Margoni paper is an important step towards understanding how 3D scanning may be treated in the EU. The next step is making sure that those rules arc towards openness and accessibility for all.

This post originally appeared on the Shapeways blog.