David Byrne’s op-ed in the Times on Sunday got me thinking about the importance of information sharing in online music services. In that spirit, I decide to throw up this unpublished whitepaper from 2011-12 on ways forward for online music licensing. Central to the idea is complete transparency on who is consuming what. It provided a way for unlicensed services to become licensed and to minimize the economic value of unauthorized music distribution. It certainly has its flaws (it fails to appreciate the importance that labels put on pricing different songs differently, which may or may not be a legitimate thing to consider in this context) but I’ve always kind of been partial to it. Remember that at the time this was written Spotify had pretty much just launched in the US and its licensing situation was from from clear. Anyway, for posterity’s sake here is the text of the whitepaper. It never had a title.

The fundamental idea is that instead of subscribing to a service, you subscribe to music. You can take your music subscription to any service that offers you music in an interesting ways. That way, instead of competing on the licensing deals that services can cut, services compete on being good at helping you to experience and discover music.

Background

The music industry provided many people their first opportunity to consider how the internet would impact existing industries. Napster became synonymous with the first widely recognized internet “crisis.” The RIAA, the lobbying organization representing record labels, has been a driving force behind both strengthening digital copyright laws and enforcing those laws in court. However, even as the internet has moved from novel to commonplace, after almost fifteen years the music industry has not yet fully come to terms with the realities of digital distribution.

Although the music industry was one of the first industries to be impacted by widespread consumer access to the internet, it has lagged behind others in finding ways to adapt to the new connected digital landscape. In fact, “avoid being like the music industry” has become something of a guiding principle for other industries facing similar digital disruption.

Period of Stability

That is not to say that the music industry[1] has not taken important steps towards engaging with the internet. Compared to the apocalyptic rhetoric and wall-to-wall litigation of the early 2000s, the current online music landscape appears to be relatively stable. It is easy and convenient to pay for music files from services such as iTunes and Amazon. Google, Amazon, and Apple (among others) are beginning to offer consumers ways to stream their music collection on demand from an internet connected device. Grooveshark, Turntable.fm, and Spotify give consumers on-demand access to a wider range of tracks. Pandora creates customized radio stations for each individual user.

This stability does mask problems, however. Compared to many internet sectors, the online music landscape is not diverse. Large companies dominate the market for purchasing music downloads. There appear to be few, if any, opportunities for startups to enter the pure download market. Even Apple’s “revolutionary” iTunes store simply met a need that had been clearly expressed by consumers for years. Only in the music industry are such late-to-market developments like selling single tracks and albums digitally online considered milestones.

Streaming is similarly hobbled. Large incumbents are just beginning to offer consumers the option of streaming the consumers’ own music collection online. Smaller companies trying to offer similar services have been smothered by lawsuits.[2] Services such as Grooveshark and Turntable.fm, unlikely to be able to negotiate full licenses with major record labels, rely on a combination of relatively untested legal theories and limited licenses to protect themselves from liability. Pandora struggled unprofitably for years, fighting with record labels for an economically viable licensing agreement. Even Spotify, the darling of the online European music world, took two years to negotiate its stripped down entry into the United States market. Even now the “successes” in this area are trailed by complaints from many sides regarding any number of issues.

There is a reason that there are so few truly successful startups in the digital music world: licensing. For the vast majority of music startups, it is simply impossible to negotiate an economically viable music license. For this reason, veteran venture capitalist Tony Conrad has compared investing in digital music startups to fighting the Vietnam war.[3]

The music industry has been unable to tap into the startup culture that is creating thousands of new killer apps and exciting services.[4] These apps and services would increase demand, interest, and engagement in music, hopefully to the benefit of all involved. The music industry is largely left out of the energy, excitement, and engagement of the digital world because it has not found a way to come to terms with the services that make that world spin.

Why Can’t the Industry Support Innovation?

There is no inherent reason that the music industry should be unable to support innovation and change. Many parts of the industry are in an almost constant state of change: new genres and artists are continually appearing to upend existing mainstays. Major labels have entire departments devoted to constantly discovering new content. It is clear that the music industry does not hate change and innovation in and of itself.

However, the music industry is having a hard time coming to terms with the best way to embrace the internet. Faced with diminishing profits, record labels are constantly in search of a new digital revenue stream. Unfortunately, labels also expect this stream to be able to restore revenues to industry high water marks. If a new opportunity does not offer a clear path towards hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues, many labels do not think that it is worth their time. Similarly, labels are worried that striking a smaller deal with a service that proves to be very popular and profitable will cause them to lose out on the next big thing. Essentially the record labels, like many industries, is haunted by the fear of waking up one morning to realize that they have traded analog dollars for digital pennies.

This caution has made record labels reluctant to incubate new music startups that could compete with their existing (but declining) offline revenue streams. They insist that startups pay steep advances, guarantee minimums, and accept licenses that force them to operate under slim margins and restricted feature sets.[5] Ambiguity surrounding which types of licenses are required for various types of offerings further complicates the terrain.

The shortsightedness of this strategy becomes more apparent by the day. The record labels are rapidly moving towards a point where they no longer have to worry about trading analog dollars for digital pennies because only analog pennies remain. Furthermore, the labels are beholden to a handful of large online companies (especially Apple) that were able to meet the licensing terms in the past. Instead of a diverse landscape of companies offering a multitude of music related services online, most digital music income is reliant on Apple, and to a lesser extent Amazon.

Until the record labels find a way to make it easy for music startups to innovate and grow, while at the same time paying for the use of recorded music, this pattern is likely to continue.

Solution

The absence of a straightforward, easy to obtain blanket license for online music distribution prevents the music industry from fully monetizing the strong desire of music fans to consume music online. It also effectively prevents the large number of application developers that want to distribute music online from acquiring necessary rights (or even identifying which rights are necessary). If those developers do manage to acquire those rights, the absence of a reliable license creates a looming threat that success will result in crippling licensing fees. This paper describes a workable framework for a blanket license for online music.

By design, this system allows all of the parties in the music industry to focus on what they do best. Artists can focus on making music. Labels can focus on nurturing and promoting talent. Collective rights organizations can focus on tracking, collecting, and distributing money. Equally importantly, it brings a new party into the industry: application developers. The license allows developers to focus on designing new ways to get people interested in music (and interested in paying for music) instead of negotiating complex licensing agreements. The public will be able to purchase a license and be allowed to access music however they see fit.

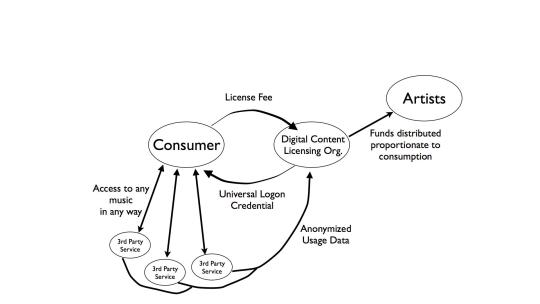

Briefly, the proposal is for a voluntary collective license. Users pay a monthly fee to a digital content licensing organization. In return, they get a username and password that they can bring to third party services to access music in any number of ways: streaming, downloading, curated stations, etc. In exchange for reporting usage statistics to the digital content licensing organization, any third party can get permission to distribute music. However, third party services do not receive a percentage of the license fee: they are responsible for creating other revenue sources. The digital content licensing organization then distributes the collected fees to artists proportional to public consumption.

By providing the public with all of the music they want, delivered in the manner they prefer, while at the same time creating a dependable revenue stream for artists, this license will serve as a way for the music industry as a whole to embrace digital distribution. As an additional bonus, it will avoid making the industry uncomfortably dependent on one corporation or entity for its profits.

Nature of the License

The license will be voluntary. This aspect serves a number of important goals. First, it is the only politically feasible way to create the license. Rightly or wrongly, the digital public does not trust the music industry. Imposing a required fee on all Internet connections, or all digital devices, or on anything else, will be seen as an attempt by a struggling industry to tax innovation. This perception will be compounded because, if a mandatory fee were to be imposed on the public by the music industry, other industries (such as the news, movie, and publishing industries) would quickly insist on a similar fee.

Second, the parties responsible for collecting a mandatory fee are unlikely to enthusiastically participate. ISPs have expressed skepticism about involvement in any sort of fee collection, be it voluntary or mandatory. Becoming the fee collectors for the music industry, and essentially becoming the public face of a potentially disliked program (if it is mandatory), is unlikely to appeal to any intermediary.

Third, a voluntary license provides a check on the music industry. Customers will feel that they have the power to opt out of the license if they are no longer interested in acquiring new music. Although such opting out is unlikely to occur in large numbers, simply having the option to stop payment will go a long way towards public acceptance of a license fee.

Finally, a voluntary license allows people who are not interested in music to avoid paying for it. If a consumer is interested in music they can pay for music. If they are uninterested in music, they can avoid doing so. While the percentage of people who are completely uninterested in music is relatively small, such people do exist. Financially supporting musicians cannot be a prerequisite for Internet access. The music industry does not want to be regulated as a public good, and therefore can not have the power to impose general taxes for support.

Creation of Third Party Applications

One of the most important parts of the collective license is that it will allow for the creation of a diverse group of third party applications and stores dedicated to convincing people to become more engaged with music. The history of music-related online startups clearly illustrates that there is a great deal of interest in creating new ways for fans to connect with music.[6] However, most of those attempts have foundered on the rocks of licensing agreements. By removing delicate licensing negotiations from service creation, a blanket license will quickly lead to scores of new music-based applications.

Although the license will allow licensees (the public) to acquire music from wherever they please, it will not automatically absolve third party services of liability for assisting in that acquisition. Services will need to comply with a handful of simple requirements in order to obtain their license to distribute content to members of the public licensed to receive it.

The most important of these requirements will be to report the activity of its users to the digital content licensing organization. This reporting will be done in an aggregated, anonomized way that will reflect which songs are being accessed, but not in a way that would compromise the privacy of individual users. The digital content licensing organization would establish a standardized reporting process that would allow services to automatically deliver usage data. This data would be used to calculate payments to artists and rightsholders.

Another requirement would be that users log in to use the authorized services. When users pay for their license, they will receive login credentials (i.e. a username and password). In order to access online music services, the consumer will enter those credentials. This validation process could occur once (associating a license username and password with a specific account on a specific service) or on an ongoing basis (using the license username and password as the login credentials for a specific service). Existing fraud protections could largely prevent a single account from being shared between large numbers of individuals.

Beyond these relatively simple and easy to implement requirements, third party applications would be free to distribute music however they see fit. This would make it easy for existing black market applications to become legitimate, licensed communities capable of attracting investors (if they were so inclined). Applications could offer track downloads, track streaming, curated radio stations, custom mix tape downloads, or any other way they chose to package music. Because applications would not receive a percentage of the license fee, it would be up to them to develop a profitable business model.

Scope of the License

The license must include both downloads and streaming of tracks. While there may have been a time when there were clear distinctions between downloading and streaming music, that time has clearly past. Any number of services now allow consumers to stream entire music collections on demand to connected devices. Although there are important distinctions between downloading and streaming in the context of track ownership, innovative services should have the ability to combine these offerings as freely as possible.

Both downloads and streams should be covered by the license. That does not mean they should be compensated identically. The compensation section (below) will address how best to accommodate these differences when allocating payments to artists.

Point of Sale

One potential place for consumers to purchase their license is with their primary Internet connection as an addition to their monthly bill. After all, some sort of Internet connection will be a prerequisite for using the license. The license will be billed in monthly cycles. It will cover an entire household, just as Internet service does today.

However, ISPs as a point of sale are not ideal. In many instances, customers have at least two ISPs – wireless and wired. Being asked to purchase a license twice could lead to confusion.

Instead, the license could be offered directly to consumers by the digital content licensing organization. Although allowing consumers to purchase the license directly from the digital content licensing organization might have a negative impact on the initial subscription rate, in the medium and long term it could prove to be a more sustainable model. It would also remove a burden from ISPs and simplify the payment chain.

Counting

It is reasonable to assume that the vast majority of users would migrate to “legitimate” platforms once they are available. This would occur both because new, attractive services would appear and because many existing darknet services would incorporate the license into their operation and “go legit.” Among other things, this would allow these services to attract a broader, more lucrative set of advertisers.

As a result, most of the use data would come directly from the information that apps reported to the digital content licensing organization. If this did not occur, the per-use counting could be augmented with statistical sampling techniques from other sites. Of course, the digital content licensing organization would also implement measures to combat clickfraud and other attempts to artificially influence the data.

Compensation

The digital content licensing organization will allocate payment to rightsholders based on the percentage of downloads and streams that each work received over the course of a period of time (such as a month). Streams will be weighted less than downloads, in a ratio to be determined in the future. The distinction between the two will be a simple, straightforward rule such as “if the song can be accessed without an Internet connection, it is a download.” The fixed ratio model will allow third party services to offer the public downloads, streams, or both, and to change the allocation according to market demand without having to fear being crushed by new licensing fees.

The Digital Content Licensing Organization: Rights Clearance and Division of Funds

The digital content licensing organization must be an independent, transparent, nonprofit organization. Its board would be a mix of artists, labels, service providers, and others adequate to give all parties confidence in the organization. It will be responsible for creating and maintaining an authoritative database of rightsholders, and for making that database accessible to the public. The organization will create open, standard ways for third party applications to submit usage data. It will also collect funds from users and distribute those funds to rightsholders. In order to accomplish this task, the organization will retain a percentage of the licensing fees to cover expenses. Finally, the organization would have the power to set the license fee paid by the public.

Unresolved Problems

While the blanket license solution is an attractive one, implementing it will not be without challenges. None of these challenges are insurmountable, but they must be dealt with in a realistic and transparent manner.

Creating the Index

The description of the solution simply assumes that there is an accurate way to match songs used by services with parties who should be compensated for that use. Although conceptually straightforward, today this process is far from easy. In addition to the fact that music tracks involve two distinct copyrights (one for the underlying musical work and one for the actual performance), ownership for each of those copyrights is often subdivided between numerous parties. Ownerships can be transferred in ways that are poorly documented and hard to determine. Companies with ownership interests can go out of business, and individuals can die without their estates in order.

It is no understatement to describe the creation of a universally inclusive, accurate index of music rights ownership as a holy grail of online music. The fact that such an obviously useful tool does not exist well over ten years into the online music story is a testament to how hard it is to create.

That does not mean, however, that it is impossible to create. The information needed to populate the index exists today, scattered across various organizations and companies. Organizations like ASCAP and Harry Fox Agency have indexes that they use to license works every day. Record labels generally have the information necessary to license performances in their catalog. The challenge is to find a way to convince all of those organizations to share their information, and then standardize and unify what they share.

Dealing with Non-Licensed Works

Without statutory backing, the license must be a voluntary license. That means that artists would be free to choose to join the license or to not join the license. As a result, it is possible that some artists would remain outside of the scope of the license.

Of course, this problem is not limited to the license discussed in this paper. Existing collective rights organizations, such as ASCAP and BMI, also offer blanket licenses that are voluntary. While some artists could theoretically decline to license their songs through ASCAP and/or BMI, prowl the streets waiting to hear their songs performed publicly, and then sue the establishment for copyright violation, in practice this rarely happens.

There is a simple reason for this – signing up with ASCAP is an easy way to guarantee a revenue stream from public performances of a work. Instead of patrolling the world for copyright violations, the artist can focus on making music. Also, the ubiquity of being “in” the license means that licensed music is effectively cheaper than music outside of the license. Once a business owner has paid for an ASCAP license, any money paid to license other music is an additional expense.

Ideally, the same dynamic would occur with the license proposed in this paper. The digital content licensing organization would control a large pot of money, and be looking to distribute that money. Most rightsholders would see the value in participating in that process and focusing on music, instead of going it alone and patrolling the internet for violators.

Streaming/Downloading Price Differences

The fees paid to the digital content licensing organization would be distributed proportionately to rightsholders. It is legitimate to consider how to take into account the real differences between streaming and downloading when making this calculation.

As noted above, defining the difference between downloading and streaming can be complex, but simple rules of thumb could be applied. The key distinction could turn on the accessibility of the file when the device is not connected to the internet. Alternatively, it could rest on what happens to the file if the user stops using the service. True ownership of a file that persists after service cancellation is more valuable than access conditioned on paying monthly fees.

In any event, the ultimate question is not necessarily how to define the distinction between streaming and downloads, but rather how to set the compensation rations. How many streams of a song should count as one download? This negotiation may be somewhat easier than it has been in the past because the result will not result in increased costs for users. Instead, the outcome will only impact the percentage of the funds collected that will be distributed to a specific rightsholder.

Conclusion

This kind of sharing agreement where fans pay for music, artists get paid, and innovators can innovate in a predictable licensing environment is an intuitively attractive solution to many of the challenges in today’s music industry. It is, unfortunately, by no means an easily implemented one. However, the goal of this whitepaper is to succinctly describe a possible solution in hopes of giving all parties a single goal to work towards.

Naturally this is not the first time such a solution has been proposed, nor will it be the last. Neither is it the only possible solution. Artists are by their nature creative, and the internet gives them a near limitless sandbox in which to experiment with new business models. New labels are forming with the goal of working with the opportunities presented by the internet. Some innovators are finding ways to raise funds and obtain licenses within the existing systems. And, finally, there are people within major labels who are working hard to orient their companies towards the new reality.

The transition from analog to digital is never easy, and the music industry is no different. It is perhaps the music industry’s unique bad luck to find itself at the nexus of a history of sloppy record keeping, a legal structure that grants powerful rights in a diffuse group of people, and a product that was one of the first to be easily distributed (both legally and illegally) online. Real change will require coming to terms with all of that, and much more.

Appendix

This proposal is not the first to try and address the problems facing the music industry online and, regardless of the hopes of the author, it is unlikely to be the last. Similarly, the ideas expressed herein are build largely on the ideas of others. For other thoughtful examinations of the music licensing issue, you might consider starting with any or all of the following:

Fred von Lohmann, A Better Way Forward: Voluntary Collective Licensing of Music File Sharing, Electronic Frontier Foundation, https://www.eff.org/wp/better-way-forward-voluntary-collective-licensing-music-file-sharing (2008)

William W. Fisher III, Promises to Keep: Technology, Law, and the Future of Entertainment, Stanford University Press, Chapter 6, http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/people/tfisher/PTKChapter6.pdf (2004)

Rethinking Music: A Briefing Book, The Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/publications/2011/Rethinking_Music (2011)

Eddie Schwartz, Legalize File Sharing, The Mark, http://www.themarknews.com/articles/1305-legalize-file-sharing (2010)

Ian Rogers, How About This Instead of SOPA? My Proposal for Legislation to Proactively Combat Piracy While Encouraging and Open and Innovative Internet, FISTFULAYEN http://www.fistfulayen.com/blog/2012/01/a-proposal-for-legislation-to-proactively-combat-piracy-while-encouraging-an-open-and-innovative-internet/ (2012).

[1] This paper is focused primarily on the recorded music industry. This is because recorded music was traditionally the economic engine of the industry. A number of studies suggest that, while revenue from recorded music is in decline, other revenue streams such as touring are actually increasing and replacing that lost income. See, e.g. Michael Masnick & Michael Ho, The Sky is Rising: A Detailed Look at the State of the Entertainment Industry (2012), http://www.techdirt.com/skyisrising/. However, although the decline of the recorded music industry is not synonymous with the decline of the music industry as a whole, it is significant. The proposal made in this paper is an attempt to find a sustainable way to monetize recorded music online.

[2] See, e.g. the original MP3.com.

[3] Sarah Lacy, Ask a VC: “Investing in Music Is a Little Like Vietnam” http://techcrunch.com/2011/02/25/ask-a-vc-investing-in-music-is-a-little-like-vietnam-tctv/ (Feb. 25, 2011) at 19:23.

[4] Experiments like OpenEMI and Cantora Labs are certainly encouraging, but fall short of a full-scale commitment by the industry. Furthermore, while musicians can (and are) free to experiment online, doing so today generally means turning away from the label system. Among other things, this can make it harder for the artist to provide a centralized contact point for easy licensing.

[5] For an excellent discussion about the challenges associated with creating a music startup, see Dalton Caldwell’s 2010 presentation to Y Combinator’s Startup School available here: http://techcrunch.com/2010/10/20/imeem-founder-dalton-caldwells-must-see-talk-on-the-challenges-facing-music-startups/. See also Michael Robertson, Why Spotify can never be profitable: The secret demands of record labels, http://gigaom.com/2011/12/11/why-spotify-can-never-be-profitable-the-secret-demands-of-record-labels/ (Dec. 11, 2011).

[6] One notable example of many is Björk’s iTunes app Biophilia, http://itunes.apple.com/us/app/bjork-biophilia/id434122935.