Image: Philip Pikart CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported

update: a better edited (thanks Torie!) version of this post ran in Slate two days after I posted it here. In the interest of simplicity (maybe?), I have appended the full Slate version below.

Today, after a three year legal battle, artist Cosmo Wenman released high quality scans of the Bust of Nefertiti currently residing in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. This is the culmination of an extraordinary FOIA effort by Cosmo and he is rightly being commended for pushing the files into the public. You can download the files yourself here and I encourage you to do so.

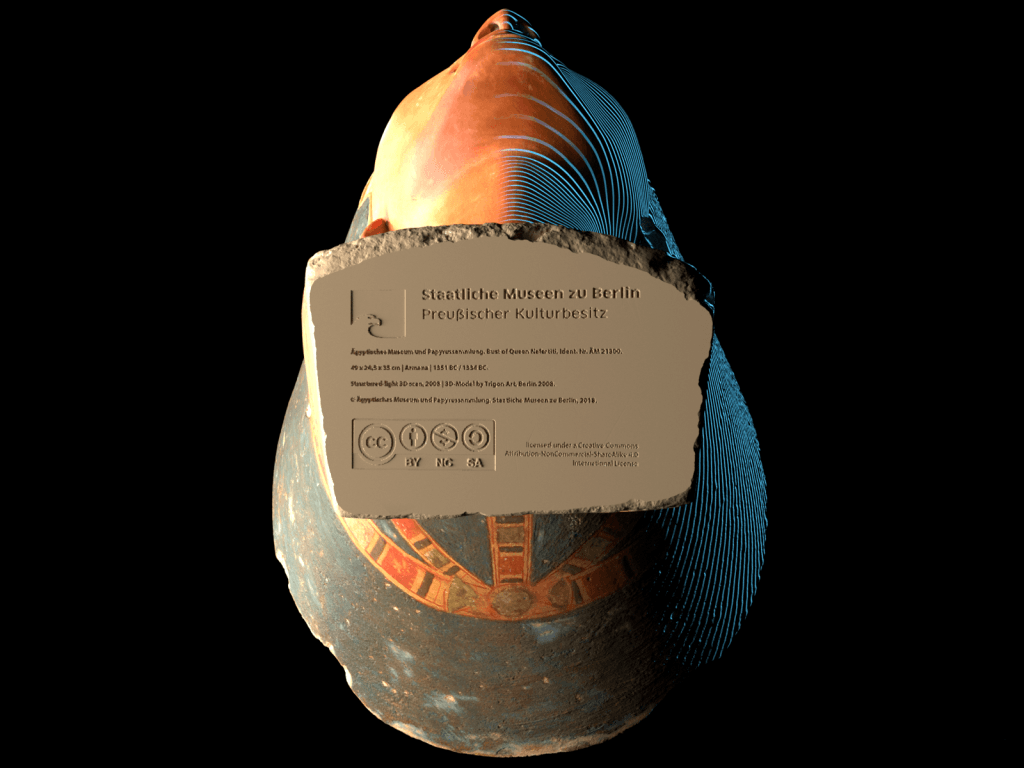

Unfortunately, the files come with a strange and unexpected caveat - a license carved directly into the base of the file that purports to restrict their commercial use.

Image: Cosmo Wenman CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Why can Cosmo license this image? I would argue because he added the blue lines on the side to try and suggest digitization, which is a creative act that is at least arguably protectable.

Is that restriction even enforceable? Is the museum that created the scan just trying to bluff its way into controlling the scan of the bust? I’m writing about it so you can guess that the answer is probably yes. But let’s go a bit deeper.

Background

The Bust of Nefertiti was not a random target for this effort. In 2016 a pair of artists claimed to have surreptitiously scanned the bust and released the files online. This drew attention in part because of the restrictions that the Staatliche Museen generally places on photography and other reproduction of the Bust. Shortly after the announcement many experts (including Cosmo) questioned the veracity of the story.

This skepticism was grounded in a belief that the scan itself was of a higher quality than would have been possible with the technology described by the artists. In fact, the file was of such high quality that it was likely created by the Staatliche Museen itself.

Believing this to be the case, Cosmo initiated the equivalent of a FOIA request to gain access to the Museum’s scan (the Staatliche Museen is a state-owned museum). This turned into a rather epic process that ultimately produced the files released today. One of the conditions placed by the Staatliche Museen on the released file was that it was released under a Creative Commons Non-Commercial license. On its face, this would prevent anyone from using the scan for commercial purposes.

Is the Non-Commercial Restriction Enforceable?

Creative Commons licenses are copyright licenses. That means that if you violate the terms of the license, you may be liable for copyright infringement. It also means that if the file being licensed is not protected by copyright, nothing happens if you violate the license. If there is not a copyright protecting the scan a user does not need permission from a ‘rightsholder’ to use it because that rightsholder does not exist.

As I wrote at the time of the original story, there is no reason to think that an accurate scan of a physical object in the public domain is protected by copyright in the United States (there is more about this idea in this whitepaper). Without an underlying copyright in the scan, the Staatliche Museen has no legal ability to impose restrictions on how people use it through a copyright license.

While the copyright status of 3D scans is currently more complex in the EU, Article 14 of the recently passed Copyright Directive is explicitly designed to clarify that digital versions of public domain works cannot be protected by copyright. Once implemented that rule would mean that the Staatliche Museen does not have the ability to use a copyright license to prevent commercial uses of the scan in the EU.

I have written previously about the role that licenses can play to signal intent to users even if they are not enforceable. In this case, it appears that the Staatliche Museen is attempting to signal to users that it would prefer that they not use the scan for commercial purposes.

While that is a fine preference to express in theory, I worry about it in this specific context. There are plenty of ways for the Staatliche Museen to express this preference. When a large, well lawyered institution carves legally meaningless lawyer language into the bottom of the scan of a 3,000 year old bust to suggest that some uses are illegitimate, it is getting dangerously close to committing copyfraud. The Staatliche Museen could easily write a blog post making its preferences clear without pretending to have a legal right to enforce those preferences. In light of that, this feels less like an intent to signal preferences than an attempt to scare away legitimate uses with legal language.

Bonus: Moral Rights

If you have made it this far into the post, I’ll throw one more fun twist on the pile. The Staatliche Museen has added quasi-legal language to the bust scan itself by carving text into the bottom. The file itself is digital, so it is fairly trivial to erase that language (by filling in the words, cutting off the bottom, or some other means). Could the Staatliche Museen claim that removing the attribution language violates some other right?

The most obvious place to look for a harm that the Staatliche Museen could claim is probably the concept of moral rights. Moral rights are sometimes referred to as part of the catchall of ‘related rights.’ These rights often include things like a right of attribution and a right of integrity. In the United States these rights are codified (in a very limited way) in 17 U.S.C. §106A (and are therefore often referred to as ‘106A rights’, or VARA rights after the Visual Artists Rights Act that created the section).

Could removing the attribution language violate the Staatliche Museen’s moral rights? I would argue not. While removing attribution or intentionally modifying the work to remove the fake license might create problems if the Staatliche Museen was the ‘creator of the work’ for copyright purposes, that is not the case here. The Staatliche Museen did not create any work that is recognized under US (and soon EU) copyright law. That means that there is nothing for the moral rights to attach to. That being said, I am far from an expert on moral rights (doubly so outside of the US). I’ll link to any better analysis that I see in the coming days.

Update 11/16/19: Marcus Cyron brought to my attention that, for reasons related to the technical structure of the Berlin museums, the name I was using for the museum in this piece was incorrect. I have therefore changed all of the references to the “Neues Museum” to instead refer to the “Staatliche Museen”. That change aside, the substance of the post remains the same.

The Nefertiti Bust Meets the 21st Century

When a German museum lost its fight over 3D-printing files of the 3,000-year-old artwork, it made a strange decision.

It seemed like the perfect digital heist. The Nefertiti bust, created in 1345 B.C., is the most famous work in the collection of Berlin’s Neues Museum. The museum has long prohibited visitors from taking any kinds of photographs of its biggest attraction. Nonetheless, in 2016 two trenchcoat-wearing artists managed to smuggle an entire 3D scanning rig into the room with the bust and produce a perfect digital replica, which they then shared with the world.

At least, that was their story. Shortly after their big reveal, a number of experts began to raise questions. After examining the digital file, they concluded that the quality of the scan was simply too high to have been produced by the camera-under-a-trenchcoat operation described by the artists. In fact, they concluded, the scan could only have been produced by someone with prolonged access to the Nefertiti bust itself. In other words, this wasn’t a heist. This was a leak.

One of the first experts to begin to question the story of the Nefertiti scan was the artist Cosmo Wenman. Once Wenman realized that the scan must have come from the museum itself, he set about getting his own copy and making it public. He initiated the German equivalent of a FOIA request. (The Neues Museum is state-owned.) His request kicked off a three-year legal odyssey.

The museum never quite clarified its relation to the scans. But earlier this week, Wenman released the files he received from the museum online for anyone to download. The 3D digital version is a perfect replica of the original 3,000-year-old bust, with one exception. The Neues Museum etched a copyright license into the bottom of the bust itself, claiming the authority to restrict how people might use the file. The museum was trying to pretend that it owned a copyright in the scan of a 3,000-year-old sculpture created 3,000 miles away.

The Neues Museum chose to use a Creative Commons Attribution, NonCommercial, Share-Alike license. If the museum actually owned a copyright here, the license would give you permission to use the file under three conditions: that you gave the museum attribution, did not use it for commercial purposes, and allowed other people to make use of your version. Failing to comply with those requirements would mean that you would be infringing on the museum’s copyright.

But those rules only matter if the institution imposing them actually has an enforceable copyright. If the file being licensed is not protected by copyright, nothing happens if you violate the license. If there is not a copyright protecting the scan, then you don’t need permission from a “rights holder” to use it. Because that rights holder does not exist. It would be like me standing in front of the Washington Monument and charging tourists a license fee to take its picture.

As I wrote at the time of the original story, there is no reason to think that an accurate scan of a physical object in the public domain is protected by copyright in the United States. (More about this idea in this white paper.) Without an underlying copyright in the scan, the Neues Museum has no legal ability to impose restrictions on how people use it through a copyright license.

While the copyright status of 3D scans of public domain works is currently more complex in the EU, Article 14 of the recently passed Copyright Directive is explicitly designed to clarify that digital versions of public domain works cannot be protected by copyright. Once implemented, that rule would mean that the Neues Museum does not have the ability to use a copyright license to prevent commercial uses of the scan in the EU. Now, licenses can signal intent to users even if they are not enforceable. In this case, it appears that the Neues Museum is attempting to signal that it would prefer people not use the scan for commercial purposes. While that is a fine preference to express in theory, I worry about it in this specific context. There are plenty of other ways for the Neues Museum to express this preference. When a large, well-lawyered institution carves legally meaningless lawyer language into the bottom of the scan of a 3,000-year-old bust to suggest that some uses are illegitimate, it is getting dangerously close to committing copy fraud—that is, falsely claiming that you have a copyright control over a work that is in fact in the public domain. The Neues Museum could easily write a blog post making its preferences clear without pretending to have a legal right to enforce those preferences. In light of that, this feels less like an intent to signal preferences than an attempt to scare away legitimate uses with legal language.

The scary language has real-world consequences. These 3D scans could be used by people who want to 3D-print a replica for a classroom, integrate the 3D model into an art piece, or allow people to hold the piece in a virtual reality world. While some of these users may have lawyers to help them understand what the museum’s claims really mean, the majority will see the legal language as a giant “keep out” sign and simply move on to something else.

The most important part is that adding these restrictions runs counter to the entire mission of museums. Museums do not hold our shared cultural heritage so that they can become gatekeepers. They hold our shared cultural heritage as stewards in order to make sure we have access to our collective history. Etching scary legal words in the bottom of a work in your collection in the hopes of scaring people away from engaging with it is the opposite of that.