It doesn’t get a lot bigger than this. On February 25th the Smithsonian went in big on open access. With the push of a button, 2.8 million 2D images and 3D files (3D files!) became available without copyright restriction under a CC0 public domain dedication. Perhaps just as importantly, those images came with 173 years of metadata created by the Smithsonian staff. How big a deal is this? The site saw 4 million image requests within the first six hours of going live. People want access to their cultural heritage.

While this is all very exciting, I wanted to take a moment to dive a bit deeper into what I see in the licensing portion of this announcement. While there are many important parts of this announcement - like the API to actually access it, and fully downloadable data that is already being turned into interesting visualizations - the licensing decisions are worth considering as well. The Smithsonian has helped to set a new standard for how open access can work at big institutions, although there are still a few things that could use some improvement.

I also want to reflect on how this moment is the result of many years of effort and advocacy by a wide range of people. Some relevant moments in that process are Carl Malamud’s 2007 “What Would Luther Burbank Do?” effort (original and archive) (one rule of thumb about big moments in openness is that Carl was usually there years earlier laying the groundwork), Michael Edison’s work on the Smithsonian Commons (the best links I have are here and here, although I’m happy to update if anyone has something better), the Cooper Hewitt’s decision to release its metadata under CC0 (followed by the 3D scan of the entire building and their font (that I used quite recently) to boot), and the Smithsonian’s own study on the impact of open access on galleries, libraries, museums, and archives (not surprisingly, written by Effie Kapsalis, who would go on to spearhead this open access move by the Smithsonian). The Smithsonian’s decision to start making 3D models of its collection available online (lead by Vince Rossi) also helped lay the groundwork for the inclusion of 3D in this release. While these efforts are worth mentioning for many reasons, one is as a reminder that advocacy takes a long time and is made up of many smaller steps. Big things don’t just happen.

Make it Easy for Good Actors to be Good

Some people will see an announcement like this and immediately think of all of the bad things that could be done with these objects. While I do not dispute that bad things are possible, letting (the relatively small number of) bad actors guide thinking about open access policies does a disservice to (the relatively large number of) good actors. Copyright restrictions or terms of service are unlikely to stop bad actors from doing bad things with cultural artifacts. However, they create significant barriers to good actors doing good things with them. Access regimes should be designed to empower good actors, not to try and slow down every possible fringe bad actor. That seems to be largely how the Smithsonian approached this effort.

CC0 By Default

CC0 is a public domain dedication that clarifies that the Smithsonian is not making any claim of ownership over the digital files it is releasing. The cultural objects included in this release are all in the public domain, so the use of CC0 is not intended to address copyrights attaching to the objects themselves. Instead, CC0 is a way for the Smithsonian to indicate that it does not have any additional right in the digital file as distinct from the object it represents.

This is important in both the 2D and 3D context. In the US it is fairly clear that a digital copy of a 2D work does not get its own copyright. That is also true for 3D scans in the US. The EU is taking steps in that direction as well. The legal status of 2D images of 3D objects is a bit more ambiguous, as is that of 3D models (created in CAD instead of by scanning the object) of cultural artifacts. There is also a lingering possibility that some jurisdictions could take the law in a completely different directions.

While the weight of legal and logical authority suggests to me that the vast majority of digitizations of public domain objects do not get their own copyright protection, CC0 waives away that ambiguity and comes down clearly on the side of openness. In addition to being right on the law, I believe that this decision is right on the theory. Creating an accurate reproduction of a work in the public domain should not give you a right over it.

In the 3D context I really appreciate that the Smithsonian is applying CC0 to scans and reproductions. See, for example, the scan of the Apollo 11 Hatch:

That file is pretty unambiguously in the public domain and released under CC0. The copyright status of the CAD model of the same hatch is slightly less clear. Nonetheless, Smithsonian decided to clear up any ambiguity by using CC0.

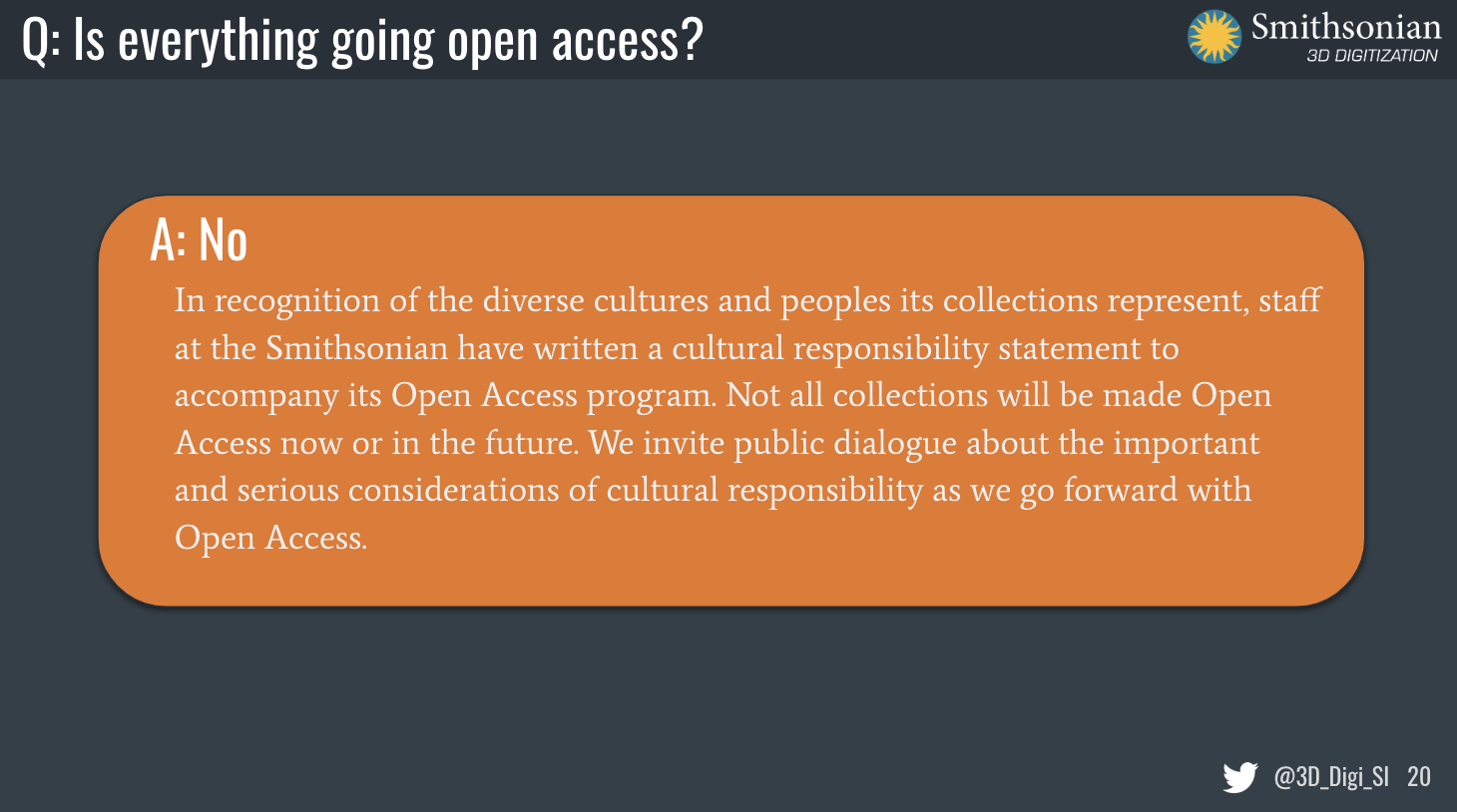

Not Everything is Open

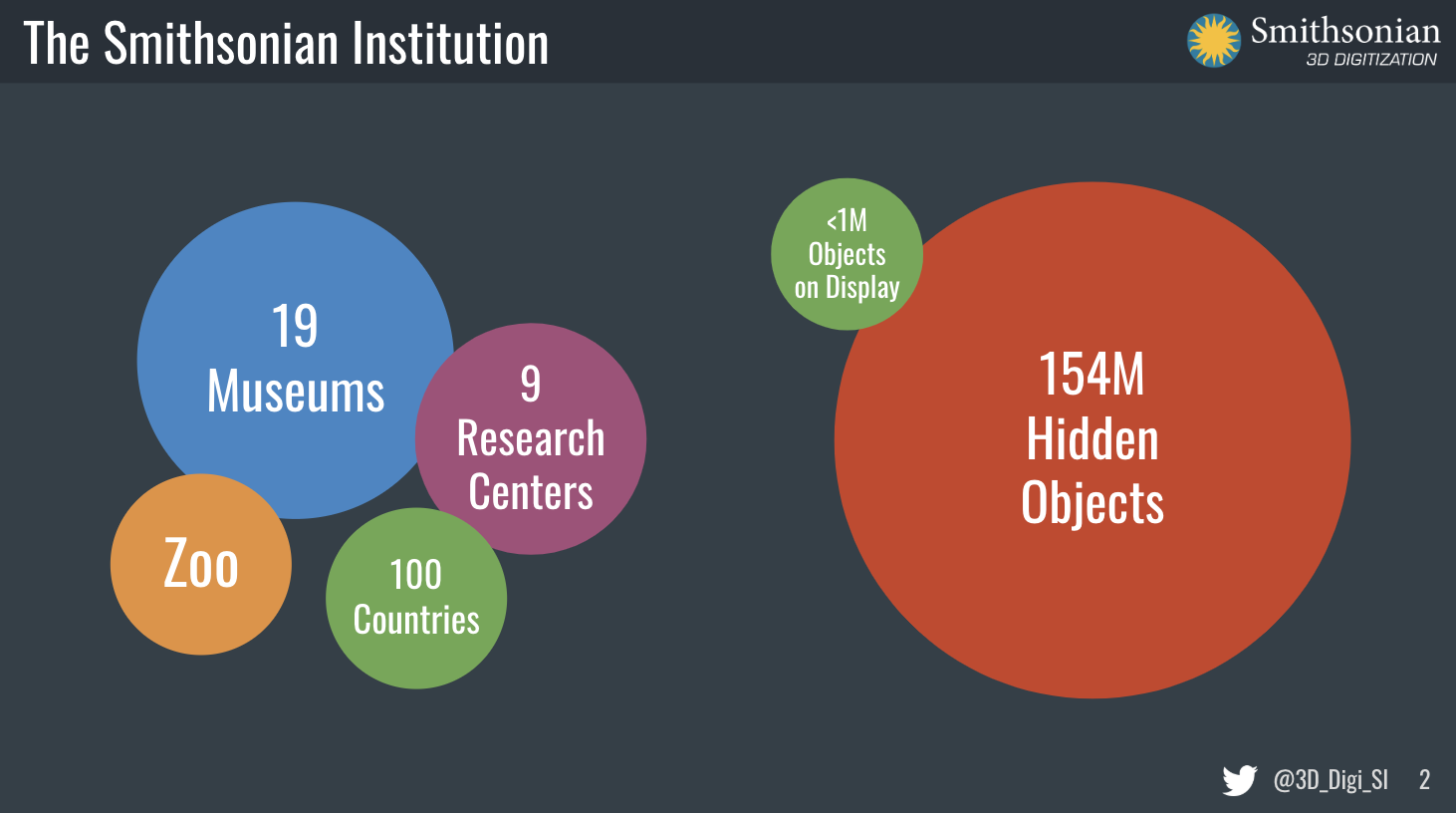

2.8 million files is a lot of files, but it is far from everything in the Smithsonian’s collection. As this slide from the Smithsonian’s 3D Digitization Team makes clear, there are still many objects left to digitize:

Some objects have not been digitized yet because they simply have not made it to the front of the queue yet. Others have been digitized but have not been included as part of the full open access program. In many cases, that is fine too.

One example is this scan of the “Project Egress” Apollo 11 hatch reproduction.

This is a scan of a replica of the Apollo 11 hatch created by Adam Savage as part of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11. Unlike the original hatch, there is at least an argument to be made that the reproduction is protected by copyright. If the underlying object is protected by copyright the Smithsonian may not have the legal ability to release the files under CC0. So it didn’t.

It is OK to Keep Some Things Out of the Open Access Program

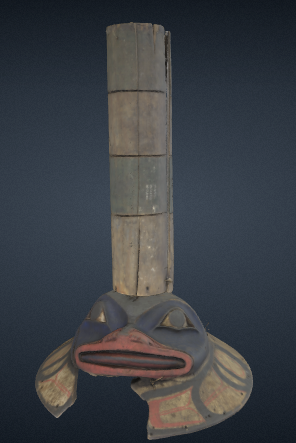

The more interesting example is that of the Sculpin Hat.

The hat was a ceremonial object of the Tlingit clan of Sitka, Alaska. It was purchased in 1884, which means from a copyright standpoint it is in the public domain. The Smithsonian scanned the damaged hat in order to create a restored replica for the clan in 2019. That means that they have the scan. And, while the scan is up on the 3D portal for viewing, it is not released under a CC0 license or even downloadable.

Why not? Because there is more to an open access program than copyright considerations. As the digitization team notes, there are cultural reasons why an object might not be included:

These are complex questions without easy answers, and it is quite reasonable to want to engage in good faith dialogs about them with all of the stakeholders before releasing the digital file without restriction. The Traditional Knowledge labels project is another interesting attempt to begin to engage with these questions.

If Works are Kept Out of the Open Access Program, The Smithsonian Needs to Explain the Rules

While the Smithsonian’s instinct to hold some files back in a reasonable one, it needs to do a much better job of explaining them to the public.

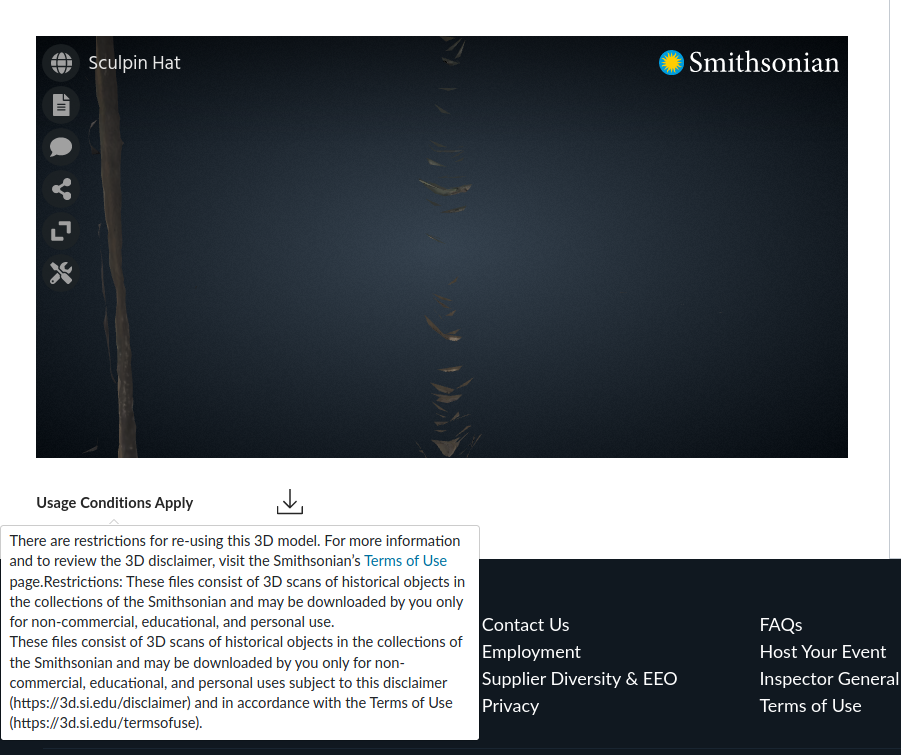

The Sculpin Hat has a notice that ‘Usage Conditions Apply’

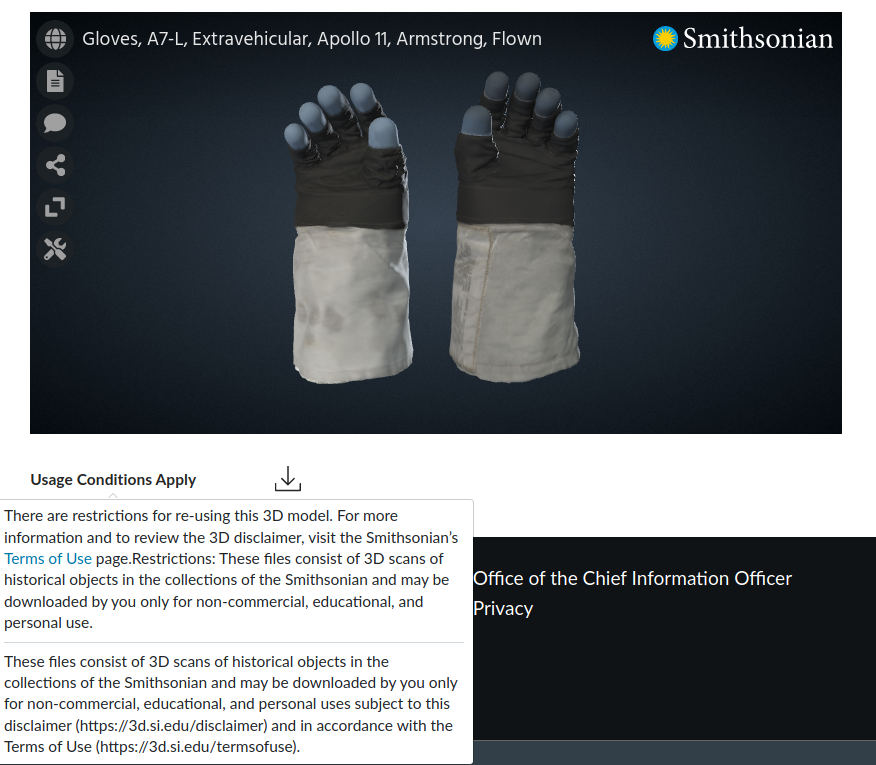

The same notice applies, somewhat unexpectedly, on the 3D scans of the gloves worn by Neil Armstrong on the Apollo 11 mission:

There are at least two problems with this state of affairs. First, the Smithsonian’s use conditions allow for “non-commercial, educational, and personal uses”. However, the files are not actually available for download on the portal. That means even uses within the Smithsonian’s rules are not possible yet.

Second, the popup notice makes it exceedingly unclear how the Smithsonian is imposing these conditions on users. Are these restrictions based in copyright law? If so, and there is no copyright in either the scanned object or the scan file, does that mean that these restrictions are not legally enforceable?

Alternatively, the restrictions may be based in the Smithsonian’s Terms of Use. Assuming the Smithsonian structured the download in a way that required users to agree to those Terms, those Terms could be considered a contract between the Smithsonian and the downloader that governs the use of the files. Basically, the Smithsonian could say that as a condition of accessing the files a downloader has to agree to their terms - that would allow the Smithsonina to impose rules without relying on copyright law. However, as currently written, the Terms of Use also seem to frame the Smithsonian’s control over the files as a copyright issue, not an access issue. The usage conditions section of the terms reads in part:

All other Content is subject to usage conditions due to copyright and/or other restrictions and may only be used for personal, educational, and other non-commercial uses consistent with the principles of fair use under Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act. All rights not expressly granted herein by the Smithsonian are reserved…

It is fine for the Smithsonian to reserve rights that exist. But framing the use restriction in the context of copyrights that do not exist is exceedingly confusing, if not legally invalid.

As discussed earlier, the Smithsonian may have valid reasons to want to limit access to some digital files. That being said, it also has an obligation to create and describe those limitations in a legally coherent way.

As I said at the outset, this is an exciting time for open access. The Smithsonian’s decision to release a large number of objects and to include 3D objects should help set the standard for open access going forward. While this effort - like all open access efforts - is a work in progress (I can’t help but notice that the Presidential Portraits collection is missing at least one portrait that we know exists, and I know of a few more works that people want to get in the 3D scan queue), it is largely being done with intentionality and thoughtfulness.

While I know that there were many, many people involved in this effort at the Smithsonian, I want to say a special thank you to Effie Kapsalis and Vince Rossi for the crazy amount of work and persistence they put into making this happen. I’m also heartened that my Engelberg Center colleague Neal Stimler was involved in making all of this happen. When an institution as big as the Smithsonian does something like this it makes a huge splash, but that does not mean getting it to happen is easy.

And one last thing - if you want to start imagining what you can do with all of this new culture at your fingertips, there’s a whole page of examples of things that talented artists have done so far.* You could even start with this book.

*I could write a whole other blog post about how important it is to go beyond releasing objects in an open access program and actually model use of those objects by recruiting creators. And maybe I will. But not today. This post is already way too long.

Feature image: Copying in the Louvre by Alfred Henry Maurer