There have been a fantastically large number of maker and open source hardware responses to the Covid-19 virus. These responses are largely focused on developing stopgap solutions to shortages of medical supplies critical to fighting the outbreak. While there will be a number of lessons to be learned from studying this movement, I want to flag one in this post: the (unexpectedly?) important role that authorities should play in channeling maker energy in important directions. Unfortunately, that role’s importance is becoming clear because authorities have been slow to play it.

Grass Roots Initiatives Emerge to Create Stopgap Solutions

For reasons I will not dwell on here, over the past few weeks public health authorities have been announcing a dire shortage of medical supplies. Although everyone hopes that traditional manufacturing capacity will eventually scale up to meet demand, in the meantime a huge number of distributed efforts have emerged to try and fill the gaps. These efforts largely started by focusing on designing inexpensive and easy-to-produce alternatives to critical medical supplies such as ventilators, masks, and other personal protective equipment (PPE).

These community-driven initiatives did not purport to be better than the traditional version of the equipment. Rather, in the absence of the traditionally sourced version, they attempted to be better than nothing.

These initiatives are tapping into a deep well of engineering capacity and interest in helping out in an emergency, both of which are inspiring. Since they were often engineering-driven, these initiatives often worked on solving the many engineering-related challenges with developing and manufacturing the equipment in a distributed environment.

Unfortunately, oftentimes these efforts did not also include public health experts. This is totally understandable, as many public health experts were active in the primary effort to combat the virus. However, it meant that in many cases the projects were focusing on solutions that made sense from an engineering standpoint but were not necessarily foptimal from a public health standpoint.

At a minimum, this had the potential to make inefficient use of the engineering and community-building expertise that the initiatives did have. At worst, they could create solutions that were actually worse than having nothing at all. Naomi Wu was one of the first people I saw raising critical questions about the value of some of these initiatives (and also pointing out that the least sexy of the solutions may be the best).

The Role of Authorities

This is the point where you might expect authorities to step in with guidance. After all, public health authorities do have the expertise required to evaluate options created by distributed communities. By elevating some those public health authorities have the ability to drive efforts towards the most effective options.

Authorities in the United States have been slow to do this. Again, this is understandable - medical regulators have safety and evaluation standards for a reason, and their institutional culture rightly makes it hard to pivot from ‘this passes a formal review process’ to ‘this is a non-horrible option in a pinch.’

What those authorities do not appear to fully appreciate is that their silence does not prevent the grassroots projects from going forward. For better or worse, grassroots enthusiasm can be channeled but it cannot easily be stopped. By avoiding endorsing any of the projects, they are failing to channel the capacity to design, manufacture, and distribute stopgap solutions in productive directions.

In a crisis it may be worth conferring slightly too much validity on a solution that is only good enough. That is especially true if doing so focuses efforts away from solutions that fail to even meet the ‘good enough’ standard. Official imprimatur can also activate even more capacity to support the approved solutions. It is likely that at least some manufacturing capacity is waiting for some sort of official guidance before jumping in to help.

This dynamic is evolving. Some larger projects have recruited enough public health experts to create their own informal medical review boards. The US government has also started to release files for PPE that have been reviewed for clinical use on the NIH 3D Print Exchange.

These are all encouraging signs. However, they could have been much more effective if there were systems in place to help grassroots initiatives quickly focus on areas of highest need that were likely to be addressable by distributed design and manufacture. In addition to identifying the most promising solutions, they could also create testing protocols that allow manufacturers to verify that the objects they create match the specifications as intended.

This piece is not intended to be a criticism of authorities at this moment. The government and public health community is full of people acting in good faith to triage and address a firehose of challenges. I am in no position to second guess those prioritization decisions. Instead, this piece is intended to serve as a reminder that there are roles for the government to play in coordinating even informal networks, and in the hopes that we have plans to do so more effectively next time.

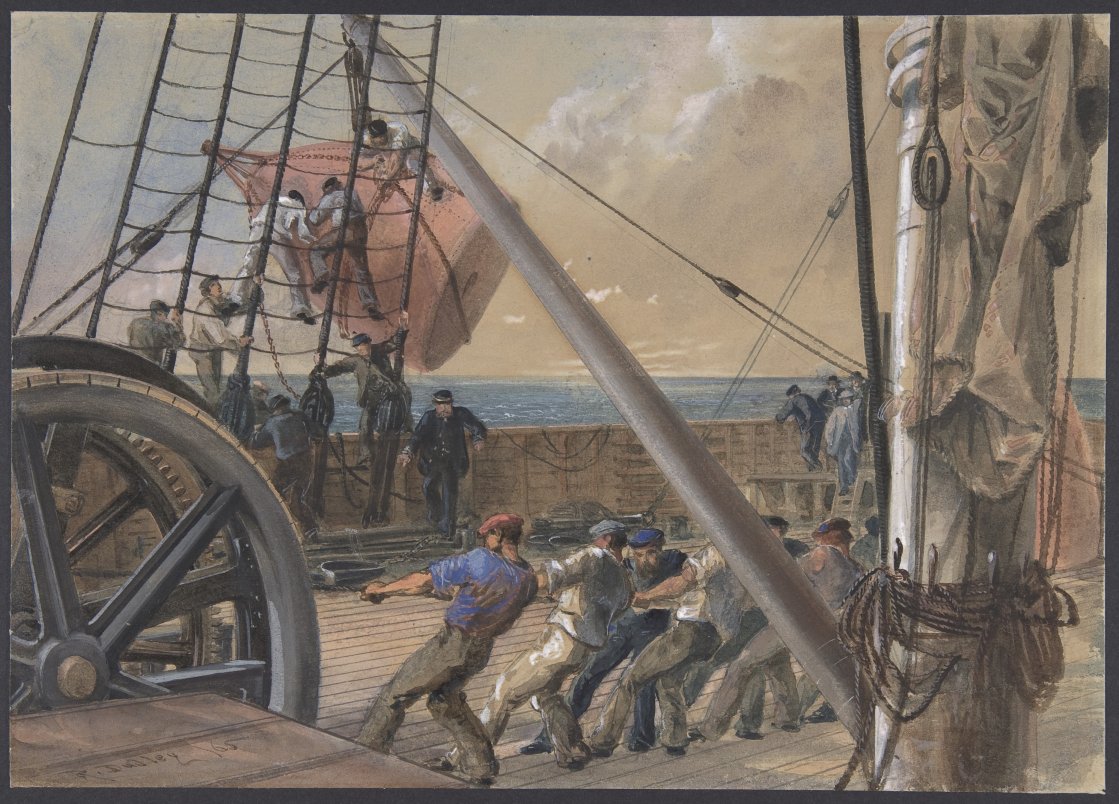

list image: Getting Out One of the Large Buoys for Launching