Last month the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced a series of partnerships that brought famous works in the Met’s collections to limited edition items from a series of brand partners. This announcement may end up being one of the most important developments for museum open access this year (and it’s been a busy year for museum open access).

In 2017 the Met made all images of public domain works in its collection available under a Creative Commons Zero (CCO) license. As commenters quickly pointed out, this open access program means that none of the just-announced brand partners needed to partner with the Met in order to incorporate works from the Met’s collection into the products.

And yet, these brands still decided to enter into a formal partnership with the Met to put the Met’s collection on their products. In doing so, they validated an important path for open access success. These new partnerships show how the power of an institution’s brand can help it monetize an open access program.

A Recurring Open Access Question - Can it Make Money?

Many cultural institutions have revenue-related internal discussions when they are considering creating open access programs. While many people argue that open access should be a core part of the mission of cultural institutions regardless of its impact on revenue, it is clear that revenue implications are part of many institution’s evaluation of open access.

Oftentimes, the discussion is tied to concerns that open access will eliminate revenue that the institution currently receives from licensing its collection. Within this context, it is first important to remember that the role of revenue from image licensing is a disputed one. A Mellon Foundation study from 2004 suggests that many institutions actually lose money on licensing because the costs of operating the program exceed any revenues associated with it. Also, the idea of licensing works already in the public domain strikes many as problematic, if not illegitimate.

Nonetheless, it can be helpful for open access proponents to have a way to address revenue concerns related to open access programs. While there are a number of ways to approach this question, many of the easiest to conceptualize options rely on leveraging the institution’s brand. Unlike the works, which are made publicly available under an open access program, the institution maintains control over its brand even if the works they control are available to everyone.

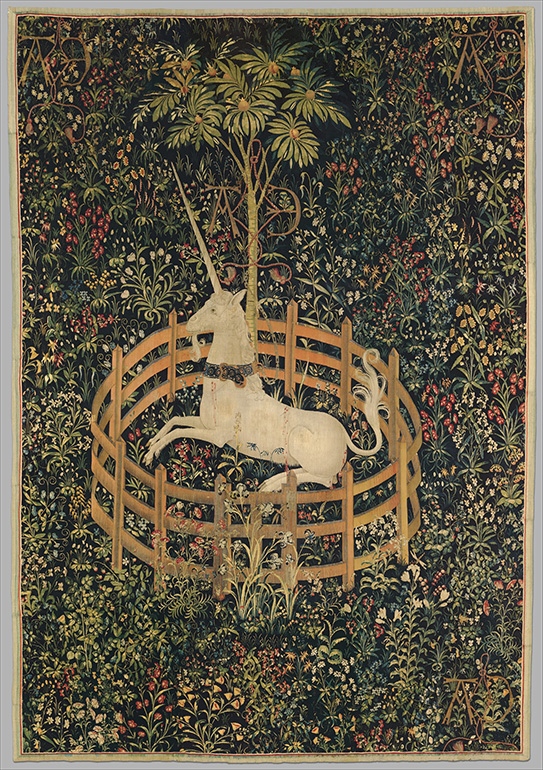

As a result, while anyone can put The Unicorn Rests in the Garden on a tote bag, only BAGGU can tout their bags as being part of “A limited collection created in collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art”. In many cases, that formal association with the institution’s brand is valuable.

How Will This Apply to Others?

Admittedly, not all cultural institutions have brands that are as prominent as the Met. However, there is likely to be a correlation between the amount of revenue an institution historically saw from image licensing and the value of that institution’s brand. That is what makes the brand licensing path an interesting one in the context of open access, and why these partnerships are especially interesting.

This program means that partnering with the Met because of its brand - as opposed to obtaining access to its collection - is interesting to a wide range of companies. Will it be successful enough to sustain their attention? Will success translate to institutions with brands that are not as strong as the Met’s? It is too early to say. Either way, it is encouraging to see the Met continue to show leadership with open access.

Feature image: A Goldsmith in His Shop by Petrus Christus