Recently I read two blog posts about the intersection of Section 230 and generative AI, specifically LLMs. While they are both interesting, I think they skip over a potentially limiting constraint on the importance of these questions: the blast radius of any specific piece of AI generated content on a website. Specifically, it seems plausible that blast radius - or damaging reach of the piece of content - may be fairly limited, which would reduce the likelihood that 230 protections end up being super relevant.*

I agree with Professor Matt Perault in Lawfare that Section 230 does not currently cover content generated by generative AI managed/hosted/whatever by a given website. I also agree with John Bergmayer over at the Public Knowledge blog that this state of affairs is a good one, at least for now.

Where I may disagree with them is how often this kind of thing is likely to come up in a context that feels 230-familiar. (I say “may” because both of them are focused on a different part of this analysis, so I don’t know how they feel about this). AI is already raising legal issues, and websites will host third party material created by AI. But today’s deployment of AI may not raise new 230 issues.

One standard 230 fact pattern is Person A posts content on Website B. Person C objects to that content (because it defames them, or causes them some other harm), and sues Website B for hosting it. In most cases, Section 230 allows Website B to step aside, telling Person C to sue Person A if they don’t like the content.

A key element of this pattern is usually that Person A’s potentially harmful content is available for many people to see. That makes the potential blast radius for harmful information quite large.

However, current generative AI usage patterns tend to be a bit different. Services like Microsoft Bing’s Sydney, or DuckDuckGo’s DuckAssist are designed to create custom content for an audience of one. That content can be hugely problematic. But in most cases the output isn’t available more broadly. That could severely limit the blast radius for the harmful information. A reduced blast radius makes it less likely the harmed party will know about the harm, and that the harm will be significant enough to justify a lawsuit.

Of course, there are two other obvious scenarios where this type of AI could create 230 issues. One is where Person A uses a generative AI service to create content, and then brings that content to Website B. In that case, the fact that generative AI was used to create the content should not be particularly relevant to Website B’s ability to get out of the suit. It would not make very much sense to have a 230 carveout for harmful content that happened to be created by generative AI.

Which brings us to the other scenario. If Person A uses Website D to generate the problematic content, Website D might be pulled into any related litigation. That seems like a fact pattern outside of 230, and pretty much what Bergmayer is contemplating in his piece. In that case, it does seem to be at least facially reasonable to allow a court to explore Website D’s liability for the content. That could even be true if the Website D content just stays on Website D. While it would be harder to discover and document, Website D creating millions of bespoke pieces of content that slander Person C does feel like something that Website D could be sued for.

*I am super aware that projecting the future impact of technology based on current use patterns can be a recipe for disaster. Sorry future Michael for any problems or embarrassment this post causes you!

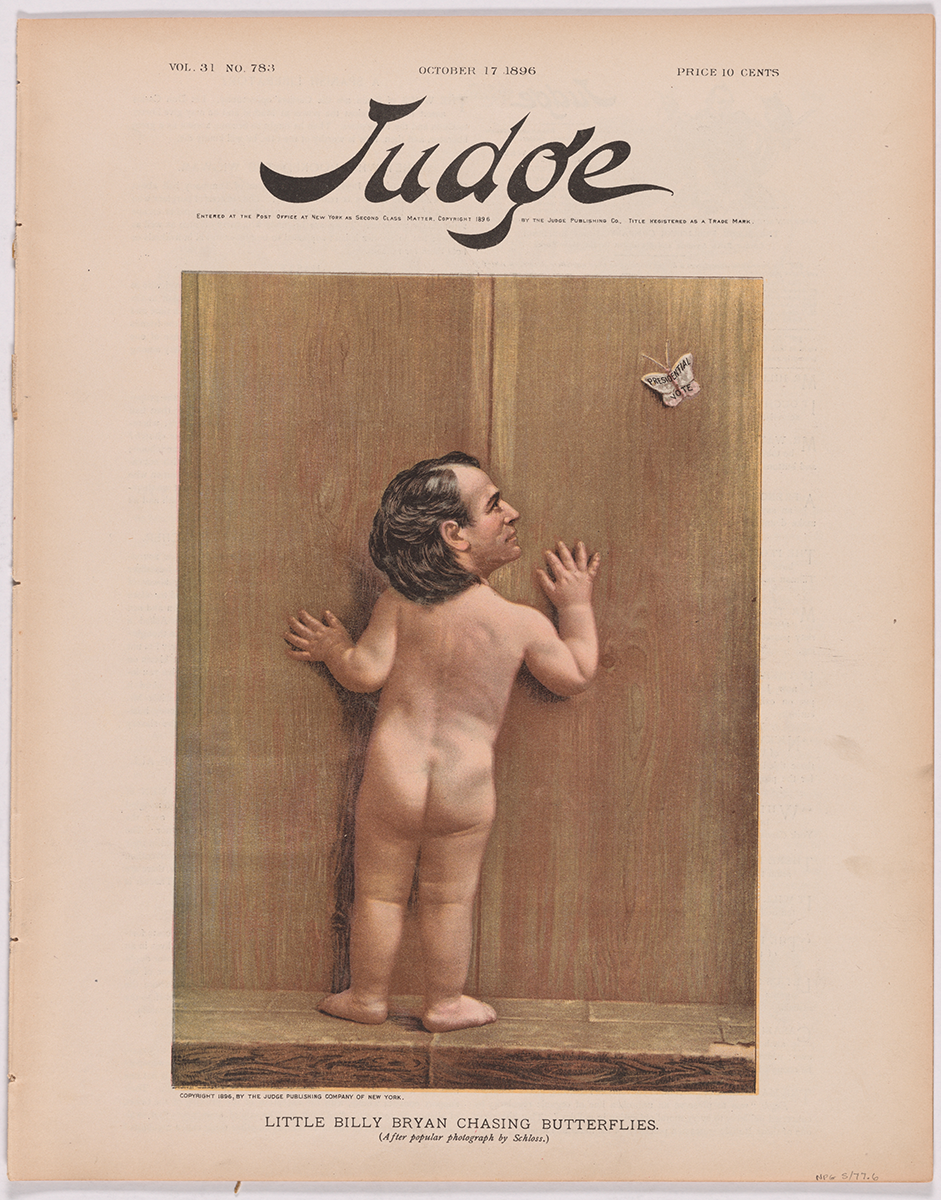

Feature image: Little Billy Bryan Chasing Butterflies from the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. I’m not going to pretend that it contains some larger commentary about this post. I was poking around looking for an image, happened to see this, and obviously needed to use it.