This week Prusa Research, once one of the most prominent commercial members of the open source hardware community, announced its latest 3D printer. The printer is decidedly not open source.

That’s fine? My support of, and interest in, open source hardware is not religious. I think open source hardware can be an incredibly effective tool to achieve a number of goals. But no tool is fit for all purposes. If circumstances change, and open source hardware no longer makes sense, people and companies should be allowed to change their strategies as long as they are clear that is what they are doing. Hackaday does a good job of covering the Prusa-specific developments, and Phil has covered other examples (I hesitate to call it a ‘larger trend’ because I don’t think that’s quite right) on Adafruit.

Still, I do believe a company that builds itself on open hardware owes the community an honest reckoning as it walks out the door. Call it one last blast of openness for old time’s sake.

Specifically, I think the company should explain why openness does not work for them anymore. And not just by waiving their hands while chanting vaguely about unfair copying or cloning. They should seriously engage with the issue, explaining how their approach was designed, what challenges it faced, and why open strategies were not up to the task for overcoming those strategies.

This discussion and disclosure is not a punishment for walking away from open, or an opportunity for the community to get a few last licks in. Instead, it is about giving the community more information because that information might be useful to it. Open source hardware is about learning from each other, and how to run an open hardware business is just as important a lesson as how to create an open hardware PCB.

What Could This Look Like?

Last year Průša (the person) raised concerns about the state of open source hardware, framing his post as kicking off a “discussion.” Members of the community took that invitation seriously. I responded with a series of clarifying questions and comments. So did my OSHWA co-board member Thea Flowers, and Phil at Adafruit. Průša is under no obligation to respond to any one of these (me yelling “debate me!” on the internet does not create an obligation on the person to actually respond).

However, kicking off a self-styled discussion, having a bunch of people respond, and then doing . . . nothing does not feel like the most good faith approach to exploring these questions. None of the questions in the response posts were particularly aggressive or merely rhetorical - they were mostly calls for more clarity and specificity in order to inform a more thoughtful discussion.

Without that clarity, we are stuck in a vague space that does not really help anyone understand things better. As the hackaday article astutely points out:

The company line is that releasing the source for their printers allows competitors to churn out cheap clones of their hardware — but where are they?

Let’s be honest, Bambu didn’t need to copy any of Prusa’s hardware to take their lunch money. You can only protect your edge in the market if you’re ahead of the game to begin with, and if anything, Prusa is currently playing catch-up to the rest of the industry that has moved on to faster designs. The only thing Prusa produces that their competitors are actually able to take advantage of is their slicer, but that’s another story entirely. (And of course, it is still open source, and widely forked.)

If moving from open to closed prevents cheap clones, how does that actually work? That would be useful information to the entire open source hardware community! If it does not prevent cheap clones, why use that as a pretext? Also, useful information to the community!

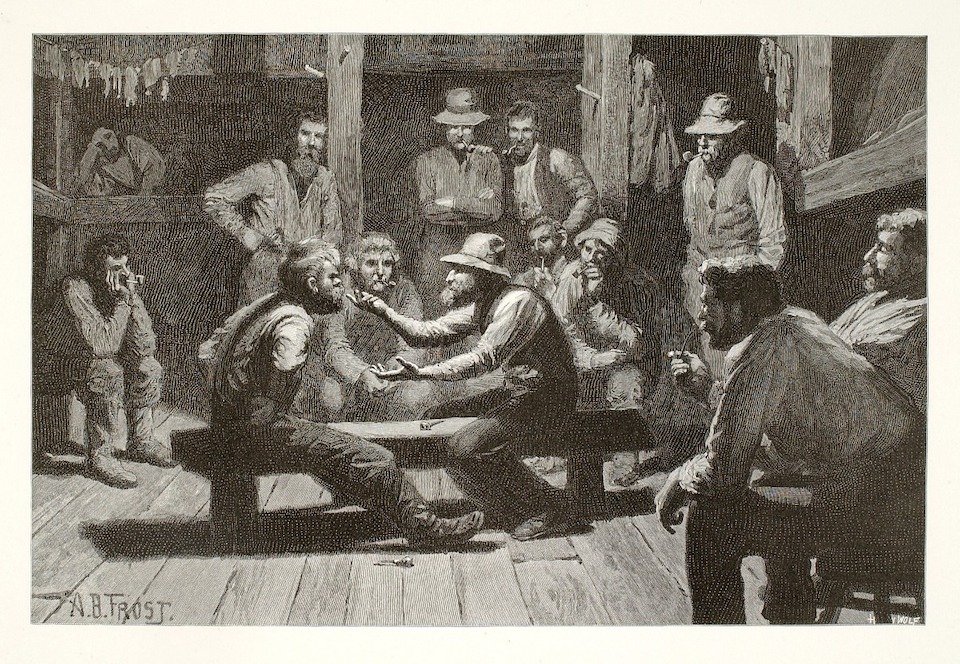

Feature image: Political Discussion in a Lumber Shanty from the Smithsonian Open Access collection