This post is a handy reference for the technical reasons why requiring 3D printers to screen for gun parts is not an effective way to reduce guns or gun violence. I am publishing it on the occasion of both New York and Washington State introducing bills to require this type of screening. In addition to a topic that I have been researching for over a decade, the question of how to know if a 3D printer is printing a gun part is something I spent a lot of time working on while overseeing trust and safety at a large 3D printing service provider.

This post is not about debating the larger legitimacy of gun control. It assumes that gun control is a reasonable and legitimate action of governments in order to focus on the technical reasons why requiring 3D printers to identify and refuse to print gun parts does not work.

Broadly speaking, it is responding to requirements that all 3D printers check prints to make sure that they are not gun parts. If the part is a gun part, the printer would refuse to print it.

The short version is that accurately identifying gun parts is incredibly hard, and the hackable nature of desktop 3D printers makes it trivial to circumvent any requirements to try.

Here’s the slightly longer version:

Matching Files is Fragile

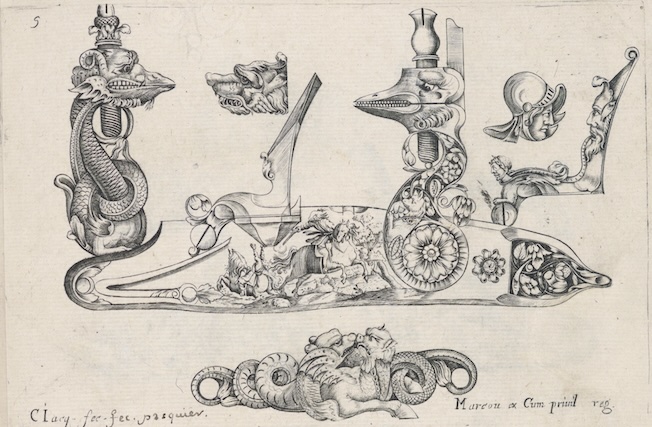

The first reason that requiring 3D printers to identify gun parts is ineffective is because analyzing 3D files is complicated. Any attempt to identify gun parts will miss many parts that are actually for guns, and may flag a number of parts that have nothing to do with guns (see, e.g. the hero image on this blog post).

Expensive engineering design software is good at evaluating specific properties of a 3D file (like where mechanical stress will occur over a lifetime of use). However, even that software can’t tell you what a part actually does (is that spring for a door, a shock absorber, or a catapult?). This challenge is exacerbated by the fact that guns are just mechanical objects. That means that there are many ways to design any individual part, and many individual parts of guns will resemble mechanical parts with totally benign uses. Put another way, devoid of other context, a switch for a gun safety looks a lot like a switch for a door.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways to think about doing file matching:

Algorithmic Analysis

This approach imagines a piece of software that can analyze a file and determine with some level of certainty if it is a gun part or just a hinge. Assuming that this software exists, which it does not at the time of this writing, it is reasonable to expect that such an analysis would be reasonably computationally expensive.

3D printers do not have the on-board processing power to do this kind of analysis. Requiring that they include chips capable of this kind of analysis would fundamentally change the economics of 3D printer design, akin to requiring that all bikes include jet engines.

Of course, the 3D printer could upload the file to a cloud somewhere and let the processing happen there. However, internet connectivity is not a default feature on desktop 3D printers. You could require that all 3D printers maintain a constant connection to the internet in order to operate but, again, that would fundamentally change how many people use their printer. There are also many legitimate use environments where constant internet connectivity is neither possible nor desirable. And, of course, this raises the question of who is responsible for maintaining that directory and keeping it secure.

Blacklisting

If it is not possible to analyze the true purpose of each file, it might be possible to at least match them against a known database of gun parts, right? This approach also has some serious shortcomings.

First, there is a question of keeping that database up to date on the printer. That would require constant, or at least regular, internet connectivity for the printer. That raises the same issues as discussed in the last section.

Second, also as discussed above, analyzing and matching 3D files is computationally expensive. The most logical way to do that with the processing power of a 3D printer would be to use a hash table of known gun parts, comparing a hash of the file to be printed against the table.

The primary problem with both geometry matching and hash matching is that it is incredibly fragile. A small change that had no impact on the functioning of the part would change its geometry or hash, effectively hiding it from the blacklist. That would make it trivial for anyone to circumvent it. Identifying which changes are functional and which are merely aesthetic is not easy. That is especially true if people are making those changes with the specific goal of tricking the printer into printing a gun part.

3D Printers Print Themselves

The second reason this proposal is ineffective is because 3D printers are made in an incredibly distributed way. There are dozens of ways to make your own 3D printer using open source, user-modifiable parts. Even non-open source printers are highly hackable.

As a result, there is no way to mandate that a technology that starts in a 3D printer remains in a 3D printer. The software that runs most printers is open source, meaning a single update would circumvent any screening measures.

This places 3D printers at the opposite end of the spectrum from 2D printers. Anti-counterfeit systems prevent 2D printers from printing currency. To the extent that these rules are effective (and I’m no expert, but they are often cited in these discussions as successful models), it is because the 2D printing industry is fairly concentrated and proprietary. 2D printer companies are actively hostile to users who want to modify their products, significantly raising the barrier to hacking around any countermeasures.

Desktop 3D printers are the opposite. They all trace their heritage back to open source printers, and users expect to be able to modify, extend, and hack their printers. That means that workarounds for a screening mandate would be easy to develop, distribute, and implement. Many open source software packages might even include the circumvention by default, meaning users would implement it without even actively intending to do so.

3D Printers are General Purpose Machines

This post is focused on the technical challenges with requiring 3D printers to screen every file it prints for gun parts. Nonetheless, it would be incomplete without a brief mention of how potentially invasive this sort of requirement is.

3D printers are general purpose machines that can be used for good or ill. Just as we do not require the phone company to monitor every phone call in order to prevent customers from using phones to commit bank fraud, we should be wary of requiring our 3D printers to monitor every print in order to prevent one possible type of print.

That type of invasion might be reasonable if it was effective. However, for the reasons listed in that post, it is unlikely to prevent even a modestly motivated person from using their printer to create gun parts. If an intervention is both highly invasive and unlikely to be effective, it is probably not an ideal policy.

Feature image: Designs for Gun Parts and Ornament from the Smithsonian Open Access collection. It’s not always easy to tell which elements of a gun are functional and which are decorative!