A designer releases a new 3D printable shoulder rig for cameras under a Creative Commons Attribution license. It quickly becomes wildly popular in the film world.

A company copies the rig but fails to give the original designer credit as required by the Creative Commons license.

An internet freak out erupts.

The company defends itself by pointing out that the Creative Commons license is not legally binding because the rig is not protected by copyright. Upon investigation, the internet realizes that the company is right. Legally, the license isn’t worth the pixels used to display it on the screen.

Weeks later, another designer releases a circuit board under an open hardware license.

Another company integrates the board into its new product, ignoring the restrictions on the license.

The designer of the original board tweets a complaint and a new internet freak out ensues. Once again, the company defends itself by pointing out that hardware is not protected by copyright, rendering the license legally irrelevant.

The internet starts calling all open licenses into question.

Prefer this article in french? Olivier Chambon has you covered.

The world is an incalculably richer place because of the open source software movement and Creative Commons (collectively, for the purposes of this post, OSS/CC). It is probably safe to say that OSS/CC has succeeded well beyond the wildest dreams of its early proponents, and has touched areas of society that would have been impossible to imagine when the concepts were being developed. Nothing that follows here diminishes that success.

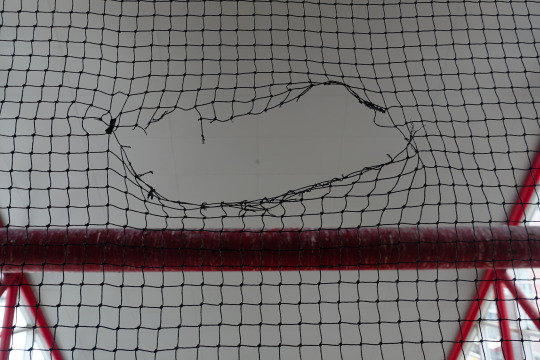

However, as they become more popular, OSS/CC licenses are starting to be stretched beyond their originally intended scope. That stretching could ultimately lead to large tears in the licenses and the communities that have grown up around them.

These tears appear because as the use of OSS/CC licenses

expands, they are being applied to works that technically, legally, they were never designed to be used with. In many of those cases, the licenses stop being legally enforceable at all. This lack of enforceability

may eventually reduce user confidence in OSS/CC and the vibrancy of the OSS/CC

community.

To be fair, the problem described in this post falls squarely

into the “good problems to have” category.

After all, the tears only exist because OSS/CC has become so wildly

successful that the ethos they embody is spreading well beyond their originally

envisioned scope.

That being said, the tears are real. At some point soon the “open” community (broadly defined) will have to come to terms with them.

OSS/CC has overflowed its original purposes. image: flickr user zoetnet CC-BY 2.0.

Fundamentally, these tears occur when the conditional sharing ethos of OSS/CC expands beyond the scope of what is actually protected by copyright. Without copyright, the conditions baked into OSS/CC become legally meaningless. The “stick” that backs them up disappears.

While I wish I had answers, this post is not intended to resolve all of the questions raised by OSS/CC spilling beyond their original boundaries. Instead, it is designed to help raise and frame the questions. It tries to explain what is going on, and to outline the potential consequences of the continued informal drift in the current direction. It also touches on some alternative approaches, none of which are perfect. While this post does not include a tidy resolution, hopefully it is a useful step in the collective process of working everything out.

Sharing “Born Closed” Works

Broadly speaking – and this entire post is going to be “broadly speaking” – OSS/CC were created to solve a specific problem created by copyright law. Copyright law automatically protects everything that is categorically eligible for protection. That means that things that are protected by copyright – software for OSS; music, movies, photos, and articles for CC – are “born closed.”

By default, digitally sharing born closed works created by someone else violates copyright law. That is because sharing works digitally involves making copies. Making copies of a work protected by copyright (in most cases) requires permission from the original creator in order to avoid infringing on the creator’s copyright.

Things like books and records are “born closed” and automatically protected by copyright. image: flickr user Michael Cory CC-BY 2.0.

That means that if you create software or music or movies and want to share it with the world, you need to take affirmative steps to give other people permission to use the work. The easiest way to do this is with a license. “I won’t sue you for sharing this” licenses make up the legal core of OSS/CC.

(With Strings Attached)

Of course, most OSS/CC licenses are not simply promises not to sue people who share the content. Many of them pair their promise not to sue with a condition. That condition is something that the open community views as a social good – “give the creator attribution,” “make the source code freely available,” “buy the creator a beer” – but that condition still serves as a limitation on sharing.

Within the world of copyrightable stuff, these limitations are enforceable because failing to follow them voids the license. And without a license, the now-unauthorized sharing is a violation of the creator’s copyright. Among other things, this has allowed to OSS/CC community to impose its ethos on people who do not care about openness. Threat of a copyright lawsuit means people and companies who just want to access the shared stuff have to play by the openness rules too.

The upshot of this situation is that OSS/CC trained a lot of people to share, but to share conditionally. This conditionality was (and is) important to creating a commons: it gives people confidence in sharing and makes them feel like they are entering a community with reciprocity. Conditional sharing has created an unbelievable rich commons of code, art, and expression.

When they are used for works protected by copyright, OSS/CC licenses are more than polite requests - they are legally enforceable.

This entire system works because it just so happened that the types of things that were relatively easy to create and share with a computer and an internet connection – code, photographs, songs, movies, blog posts – also happened to be the types of things that are automatically protected by copyright. That made the entire framework more than just a cultural norm relevant to a community of people – it was legally enforceable.

As they built the commons, people internalized the “share with conditions” model as normal. They did not necessarily appreciate that the conditions were all linked to copyright, or that copyright has limits as to what it can protect. In part, they did not realize this because the limitations were not relevant – everything at the core of the commons was protected by copyright so copyright’s boundary did not matter.

Shift and Expansion into “Born Open”

That is no longer the case. A number of technical and cultural changes have begun to bring works outside of the scope of copyright into the commons discussion. This is a testament to the success of OSS/CC – the commons are so rich and the norms so appealing that new communities naturally align themselves with it.

The OSS/CC party is getting bigger. image: flickr user Mikey Wally CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

Instead of being organized around “born closed” works protected by copyright, some of these communities are organized around “born open” works that are categorically outside of the scope of copyright. The two highest profile (or at least the two I’m most familiar with) are the open source hardware community and the 3D printing design community.

Neither of these communities are fully outside of the scope of copyright. Some parts of any given open source hardware project may be protectable by copyright, and many 3D printed objects are protected by copyright. However, the functional parts of an open source hardware project and more utilitarian 3D printed objects are beyond the scope of copyright protection (you can just accept that distinction for the purposes of this article, but there is more information on it here and here). That means that blanket assumptions about copyright protection, and licenses that are built on a foundation of copyright protection, do not apply as cleanly to born open objects (more about that here).

As a result, on some level and in a non-trivial number of cases, using copyright-based licenses for works in these communities is inappropriate. While they may look the same as the licenses on software or photographs, in a significant number of cases they will not be legally enforceable. At the same time, they are there for both creators and users to see, and to take into account. They also may carry cultural weight. That being said, the space between the licenses’ visibility and enforceability creates costs (and benefits).

The Costs and Benefits of the Current Path

To be clear, this evolution is happening right now and is actively altering the status quo around copyright and licensing. That means that ignoring this evolution and pretending it isn’t happening is a vote for this shift to keep happening. Doing something may be a vote for a different kind of shift. But, as far as I can tell, there is no vote you can cast to maintain the status quo. The only decision is between which different future you prefer to work towards.

A number of things that I would classify as negative happen if people continue to apply copyright-based licenses to works that are not protected by copyright:

- Creators’ expectations are not met. If a creator releases a work under an OSS/CC license, on some level they expect to be able to enforce the terms of that license against someone who violates it. However, if the work is not protected by copyright the terms of the license are not enforceable. As a result, there is likely to be a high profile instance of an OSS/CC license “failing” to protect a work from being used in a way that violates the original creator’s hopes. The story will appear to have a “good” creator with a sympathetic story and a “bad” violator who acts in a villainous, obnoxious way. However, the good creator will be trying to enforce rights they do not have and the bad violator will not have broken any legal rules. Everyone will be sad that the bad violator can’t be punished and people will start to worry about using OSS/CC licenses.

- Legitimate usage is curtailed. The conditions in any OSS/CC license are

restrictions on use, and those restrictions disqualify some people from making

use of the work. If the license used is

not valid, the restrictions it attempts to impose on unwilling users are not legally

enforceable. Regardless, there will be

some number of end users who 1) want to use the work in a way that violates the

terms of the license, and 2) do not realize that the license does not legally

prevent them from using the work anyway. That means that some legally allowed uses never happen.

- Copyright creeps outward. There is a deep irony in this one. Regardless of their real enforceability, if

people continue to use and see OSS/CC licenses

on works that are not eligible for copyright protection they will begin

to assume that copyright actually protects those works. They might even advocate for copyright to protect the works in order to make the licenses enforceable. The outcome of this is that OSS/CC licenses –

licenses designed to increase the pool of commonly available works – could

act to reduce the pool of commonly available works by dragging currently open works into the world of

copyright. This process could take the

form of resetting social expectations or, perhaps even more problematically from

the viewpoint of the OSS/CC community, actually be used to change the statutory

scope of copyright itself in an effort to make the licenses apply to more works.

There is also a potentially positive effect of this type of license use:

- Signals for use. The wishes of creators can be legitimate even

if they are not legally enforceable. To

that end, OSS/CC licenses can be signals to users about how creators of a work

want it to be used. There are plenty of

non-legal reasons for a user to want to respect these wishes, and using

standardized ways to communicate those wishes can make it easier to do so.

And one that could be argued either way:

- May encourage more sharing. For some creators who are not naturally

inclined towards sharing, using an OSS/CC license gives them enough of an

assurance of control to convince them to make their works available to others. You can see this on how some people evolve from more-restrictive to less-restrictive licenses over time as they become more comfortable with the idea of sharing. The positive version of the use of these

licenses on non-copyrightable work is that more formerly private works will be

released into the public for others to see.

The negative version is that the creators will be mistaken with regards

to the terms those works are released under.

I withhold judgment on how those two factors balance out.

There are some ways to address these effects. None of them are perfect, or even necessarily good ideas.

- Expand copyright or create a new

easy-to-obtain right. The problem

described here is rooted in the fact that many works are not automatically

protected by copyright or some other easy-to-obtain right which can be used as the legal basis for a license. One way to solve it is to expand the scope of

copyright or create a new easy-to-obtain right that serves a similar purpose.

While doing so would solve the immediate issue with license enforceability, it creates many more and is a

horrible idea. Converting the universe

of “born open” works into “born closed” just to make it easier to openly

license them strikes me as counterproductive.

Also, while some of the creators of these newly born closed works might

license them openly, others would likely use the new rights to restrict what

today would be a free and open creation.

- Public Education. I want to think that this alone can solve the

problem. If people really understand when to appropriately use copyright-based

licenses, this problem disappears. While

I believe strongly that public education is a key component of addressing this

problem, I’m also realistic enough to know that there will always be a massive

pool of people who have better things to fill their brains with than the

nuances of copyrightable subject matter.

Any solution has to work for those people too. That means we need more than public education.

- Create New Licenses. If copyright-based licenses don’t quite cut

it, why not draft new licenses that do? Because – like creating secure

encryption that also allows the government to freely access the protected files

– doing so is a lot easier said than done.

Copyright is a great basis for a license because eligible works are

protected automatically and without cost.

People do not have to do anything to get copyright protection. All of the other obvious hooks for other

licenses – like patent and trademark – require time, money, and affirmative

decisions to obtain. Even if some people

will take the time to obtain them just to make it easier to license their work under OSS/CC, those people will never reach a critical mass or majority.

- Stop Using Licenses. If current licenses do not protect all of

these new types of works, should people just stop using them? Unfortunately,

that’s not a great solution either.

While many works will not be completely protected by copyright, many

parts of many works are. The analysis of

which parts of which works are protected by copyright is somewhat work-specific

(because nothing here is easy), but it is safe to assume that many works will

be just protected enough by copyright that copyright could present a barrier to

some types of reuses. To the extent they

exist for a given work, OSS/CC licenses can clear those copyright-based barriers to sharing.

- Contracts. Contracts can serve as an alternative to

licenses. While OSS/CC licenses rely on

copyright to be enforceable, contracts can just rely on the agreement of two

people. The creator offers the work to a

user on the condition that the user agrees to the terms. If the user breaks the terms she has

agreed to, she is breaking the contract with the creator. The problem with contracts is that they can

only be enforced against someone who agreed to them. That is always going to be a comparatively small universe of people. Whether they like it or not, everyone is

required by law to respect a copyright. That means

that the person who receives the work directly from the creator may be limited

by the terms of a contract, but the people who stumble upon it on a random

website would not be. This global

enforceability is what makes copyright law so attractive for licenses. Its

absence severely limits the usefulness of contracts as a substitute at scale.

Decision Time

The status quo is changing. OSS/CC licenses are expanding beyond the universe of clearly copyright-protected works that they were originally designed for. That is a testament to 30+ years of community building in the open community. It also creates challenges. Ideally this is the point in the post where I would describe a clear path forward and advocate for following it. Unfortunately, I don’t have that path (yet). All I have is a phenomenon that I believe is occurring and a series of ways the world is accommodating it.

Fortunately, the open world is strong because it is collaborative. I’m already working with Creative Commons and other stakeholders to try and find some answers. Hopefully this post will pique the interest of others to join in. If it has (and let’s be honest - if you made it all the way down here it probably has) let me know.

Bonus: One thing that is connected enough to mention in a bonus but not so connected as to be worth integrating into the heart of the post is the history of the Open Game License. For all of its differences, it is another example of communities looking to licenses for openness where they probably didn’t quite fit and were not necessary. I won’t pretend to be an expert on the details of that community or the politics connected to all of it, but this article on it made a lot of sense.

top image: flickr user Nick Normal CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0.