This post originally appeared on the Shapeways blog. Although I didn’t explicitly frame it as such there, this is probably the closest thing to a distillation of a bunch of thinking about 3D printing and policy that I did in my first six months on the job. The content policy section was the result of a lot of reflection about how to draw lines on a service like ours, and the product liability section is a small public example of some long conversations I had with our product liability counsel Patrick Comerford. It also kicked off a reorganization of all of our policies to guarantee that it would be easy to find all of the previous versions of policies after they were changed, a process that my colleague Allessandra McGinnis was way, way too accommodating of me during. Anyway…

Today we’re excited to roll out a batch of updates to our policies. These updates should make Shapeways work better for you, and bring your experience at Shapeways more into line with your expectations of Shapeways. This post has detailed information about the changes. As a reminder, you can always find links to archived versions of policies on that policy’s page.

For those of you looking for a quick summary of the changes, here it is:

- We’ve revised our content policy. The result is increased transparency around what we will and will not print, opening up a number of new possibilities for models.

- We’ve updated our privacy policy. It now has an even stronger commitment to protecting your privacy, especially in the face of requests for your information by third parties and governments.

- We’ve clarified our terms and conditions. It should now be easier for you to understand who is responsible for what if a model causes harm to others.

- We’ve created special terms and conditions for our public API. They are designed to establish a common set of expectations about how the public APIs work.

Want more details? Keep reading. As a reminder, this post is designed to explain the changes that we are making today. It is the policies themselves, not these summaries and explanations in this post, that form the basis of our agreement with you.

Content Policy Update

The focus of our updated content policy is to bring additional clarity to our content rules. To that end, we have broken the policy into two sections – one for weapons and one for obscenity – and given each section a list of do’s and don’ts. These do’s and don’ts are intended to allow designers to get a more clear understanding of what types of models will result in heightened scrutiny or rejection.

Weapons

The updated weapons policy should give designers added flexibility for their creations. We continue to prohibit guns, parts that modify the functionality of guns, realistic replicas that could be easily confused with guns, and switchblades, throwing stars, and brass knuckles. These restrictions are largely grounded in laws that restrict the manufacture, sale, and possession of these items.

At the same time, we will be much more accommodating of cosplay accessories, most knives and swords, and gun accessories that are not tied to core functionality – things like mounts and grips. This should make it much easier for stores such as BrainExploder to offer camera mounts and Ammnra to offer cosplay accessories without worrying about being flagged for content policy violation.

Obscenity

In addition to weapons rules, we’re clarifying how we handle models we consider obscene. We will continue to prohibit models that embrace sexual violence, hate speech, or that are designed to denigrate living beings.

However, we do recognize that obscenity can be a tricky line to patrol. Therefore, we are committing ourselves to be responsive to designers who believe that we are missing critical context for a design that we reject for obscenity reasons. That is not a guarantee that we will change our decision with additional context, but it does mean that we will seriously consider context that we may have missed.

Implementation

In addition to more consistent rules, we’re also rolling out a more consistent internal process to enforce those rules. All models will be checked for content at the same time they are checked for printability. Models flagged for potential content violations at this stage will be sent to the Trust and Safety team for review. In most cases, the Trust and Safety team will make a decision about the model. If the model is rejected, the designer will be notified of that decision. If the Trust and Safety team is not sure, they have the option to elevate the question to the legal department, which has final say. This structure is designed to review models as quickly and consistently as possible so that models that comply with our rules can get printed and designers of models that do not comply with our rules can find out in a timely manner.

You can compare the new policy to the previous policy, which has been archived here.

Privacy Policy Update

The biggest change to our privacy policy is the addition of clear language about how we handle request for your information from government representatives and other third parties.

We take our obligations to secure the information you entrust to us seriously. We also take our legal obligations to comply with governments and courts seriously. In light of these obligations, we are adopting a policy that formally requires sufficient legal process before we disclose records about our users to governments and third parties. Generally speaking, that means that governments and third parties will need to have a subpoena, warrant, or court order in order to access your information without your permission. Those documents must have enough information to minimize the likelihood of accidental disclosure of information from unrelated accounts.

In the case of law enforcement and other governmental requests, our policy in most cases is to provide notice to a user if she is the target of a governmental request for information. If such notice is temporarily prohibited by law, it is our policy to alert the users once that prohibition has been lifted.

This general policy does not apply to emergency situations, or to a handful of other third parties who we may share your information with as a normal course of business (our shipping partners or vendors, for example) described in our privacy policy.

In addition to this significant change, the update includes a handful of smaller edits and clarifications. These include clarifying what types of emails related to our service you may receive from us, a reminder that your data may cross international borders, and how our data retention policy works.

You can compare the new policy to the previous one, which has been archived here.

Terms and Conditions Update

This is an incremental update to our Terms and Conditions, focusing specifically on the language regarding product liability. This relatively small update is designed to clarify how liability works with 3D printed models here on Shapeways. In addition to the liability portion of the update, we clarify that except in cases of fraud or policy violation we will give you a full cash refund if we cancel your order.

This rest of this part of the post is designed to help give some background information about how we are thinking about product liability and explain the changes themselves. As a reminder, you can find all of the old versions of our Terms and Conditions here, along with links to the blog posts that announced and explained the changes.

Liability and Responsibility

This update focuses on events that we wish never happen – models failing and hurting someone. While it is tempting to cross our fingers and hope that everything that is uploaded and printed will always work perfectly, the responsible thing to do is to face the possibility of error head on. That’s a big part of the role of our Terms and Conditions generally, and for the sections having to do with warranties, disclaimers, and indemnification specifically.

The nature of what we do here at Shapeways upends some of the assumptions built into the traditional thinking about product liability. Instead of large companies relying on deep, longstanding relationships to design, manufacture, ship, and sell products, Shapeways allows people working on their own to design objects and connect with buyers directly all over the world.

While this comparatively distributed and informal structure creates a lot of advantages, it also uncovers some challenges. One of those challenges is that in most cases we here at Shapeways do not really know what we are printing. That means that we don’t evaluate designs before printing them to make sure they are fit for purpose – in many cases we don’t know what “fit for purpose” would even mean. Similarly, after the objects are printed we don’t test them to make sure they will function as expected because we don’t necessarily know how you expect them to function. This does not mean that we ignore red flags or do not respond to concerns. It does mean that we cannot guarantee that a model will be well designed for any specific application. That’s why we rely on the designer’s word that the designs make sense for their intended purpose.

Nonetheless, there are things that we can guarantee. We can promise that the models will be 3D printed correctly on properly calibrated printers operated by responsible operators. We can also promise that the models will be packaged and shipped correctly. That promise means that it is our responsibility if something fails because it was printed incorrectly. However, it does not mean that it is our responsibility if a properly printed – but incorrectly designed – model fails.

Revised Language

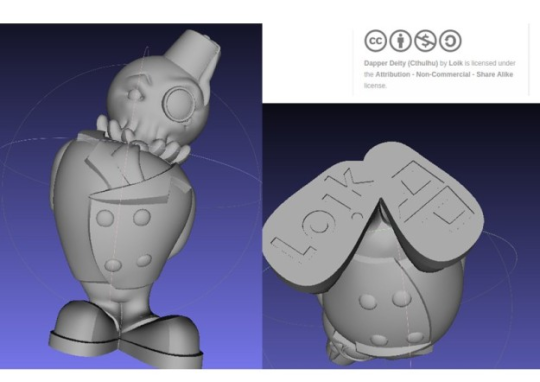

That’s the distinction that the revisions to the Terms and Conditions are designed to highlight. We have always required designers to certify that their models do not violate anyone else’s intellectual property or applicable laws because the designer is best positioned to know that information. To that list of designer responsibilities, our update adds things like relevant design and safety standards.

Similarly, we ask designers to stand behind the design specifications of their model because they are best positioned to know if the design is adequate for its intended purpose. That is also why designers are responsible for the selection of materials. Designers know which materials are and are not appropriate for a given model, so it is their responsibility to only print (or offer to print) the model in appropriate materials.

Finally, we make explicit what was already implicit in our indemnification section – namely that designers have an obligation to indemnify us in the face of a personal injury or product liability lawsuit flowing from their design. Again, this is because the designer is in the best position to anticipate – and address – problems related to design defects.

Exploring Together

As I noted earlier, Shapeways raises some novel legal questions about how product liability can work in the context of 3D printing. In updating our Terms and Conditions language, we are hoping to make it as clear as possible where we understand different responsibilities to lie. That being said, “novel legal questions” often also mean that the answer evolves over time. We’re all exploring the implications of 3D printing together, and it is entirely possible that this section of our Terms and Conditions evolves over time. If and when that happens, we’ll do our best to explain our thinking to you as we go.

New API Terms and Conditions

Still with me? The final update is not an update at all, but rather an addition. As many of you know, we have a fantastic public API. The new API Terms and Conditions are designed to make sure that everyone making use of the API knows how it works and what to expect. The API Terms and Conditions build on top of our existing site-wide Terms and Conditions. One of the advantages of that is that the API Terms and Conditions can be brief and a bit more approachably written. They clarify that we are granting API users a license, that we strive for but don’t guarantee 100% uptime, and how to handle applications that might push an especially large volume of traffic through the API.

Questions, Concerns, Comments?

And that’s the end of the update on the updates. As I stated at the top of this post, our goal with these updates is to make sure that our rules make it as easy as possible for you to understand how Shapeways works, and to make sure that Shapeways works the way that you expect it to. If you have questions, concerns, or comments about these changes, let us know. You can raise them in the comments below, in our forums, or to me directly via twitter @MWeinberg2D or email at mweinberg@shapeways.com.