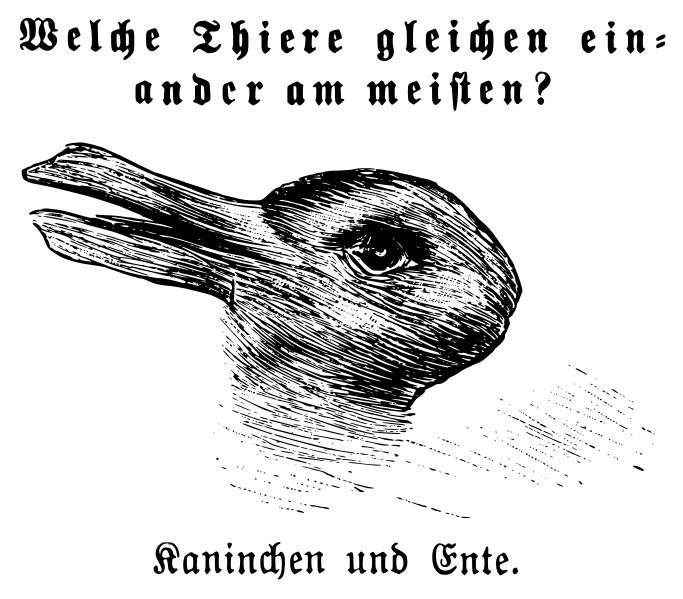

A recent kerfuffle around an open source software creator asking for their package not to be included in a larger project has turned into a kind of rabbit-duck illusion for the open source community. What does it mean when the creator of a software package uses their social power - but not their legal power - to try and influence user behavior? Are they violating the spirit of open source? Or simply making requests that acknowledge open source realities?

What Happened

The actual back-and-forth is in the pull request discussion. The citadel of internet debate that is Hacker News will give you a sense of the larger community response. Briefly, what happened was:

- The creator of an open source software package asked that the package not be incorporated into a larger project. The creator acknowledged that it was technically legal to incorporate the package, but asked that it not be included anyway.

As the author of the package that is being re-packaged here. I’m against it being repacked into here. While licensing wise I cannot stop you, I do hope you can honor my request. Thank you for considering respecting the author’s wishes.

- When pushed by the project’s maintainers, the package creator explained that they were worried that including the package in the larger project would result in many support requests from the community.

If users experiencing issues with [the package], they will knock on my door. And I’m not willing to support that or accept that burden.

- Downstream maintainers pushed for more information or explanation. The creator continued to express disinterest in having the package included and in a conversation about the decision

- Eventually the creator threatened to relicense the package in a way that would make it legally incompatible with the project

Online opinion is split on this situation. However, some substantial part of the community has responded with a version of:

Seems like an author that doesn’t understand the spirit of FOSS.

What can be learned from this? Is this kind of request really against the spirit of FOSS?

Distinctions Between What the Law Allows and What Social Norms Allow are Real and Relevant (I)

It is notable that the creator did not kick off this discussion with the threat of legal action. Instead, the creator simply requested that the package not be included. They then explicitly acknowledged that they did not have the legal power to prevent it.

This was a request that no one had a legal obligation to respect. And yet, the creator made it because (presumably) they believed that the package maintainers lived in a world that was governed by more than black letter legal rules.

This strikes me as a totally healthy response on behalf of the creator. They clearly understood the consequences of releasing software under an open source license and the potential consequences of being included in a popular software package. The creator expressed these concerns by way of a social request instead of a legal threat because part of living in society is being able to resolve disputes without going to court.

We will never know, but it strikes me as entirely plausible that the creator may have been willing to leave it at that - as a request that may or may not be complied with - until the maintainers decided to follow up.

To be clear, the maintainers’ initial response also strikes me as a reasonable one. They probably wanted to understand the concerns that would motivate someone to make the request. They may have also hoped to be able to address those concerns and/or talk the creator out of the objection.

Unfortunately, this very human response by the maintainers also happened to push the creator to do exactly what the creator was hoping to avoid by raising the concern - spend time talking to people that they do not know about their package. Eventually, after the discussion continued, the creator decided to threaten to relicense the package in a way that would legally prevent inclusion.

It is important to recognize that this discussion ran on parallel tracks. One track was based on legal requests (or the lack of legal requests). The other was based on social/cultural requests.

That social/cultural track has the potential to be just as powerful as the legal one (in fact, it is the basis for this idea). Its existence illustrates that the reasonable resolution of the dispute did not have to rely on a strict interpretation of legal rights. Society is more than the law! The maintainers could have ignored the request and faced meaningful social/cultural consequences without any sort of legal enforcement. Social norms are real and create real change in the world. Even in open source.

Distinctions Between What the Law Allows and What Social Norms Allow are Real and Relevant (II)

On the flip side, the package in question is licensed under an MIT license. That license includes a pretty clear “anything that breaks is not my problem” disclaimer (in all caps):

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

If the legal rules were all that mattered here, the text of the license makes this entire dispute a non-issue. The creator offers the software as-is and disclaims any responsibility for it. Why would anyone come back to them if the software had a bug?

Of course, the text of the license does not match social expectations. Licensing terms aside, the creator recognizes that there is a social expectation in the open source software community that creators maintain packages - or, at a minimum, that it is acceptable for users to reach out to creators to ask for support and/or flag bugs.

While the creator seems to have understood that they have no legal obligation to deal with these requests, they also understood that they might have a social/cultural obligation to deal with them. Or, at a minimum, that the tools available to open source software creators make it hard to ignore a flood of requests. No amount of pedantic textual analysis of the license terms changes that.

Another Example of the Dark Side of the Power of Open Source?

This fits in with a long list of stories about how small pieces of code are used by millions without any sort of support for maintainers of the code. In some ways, this is a success story - a random person can create something that is used by millions! In other ways, it is a tragedy - a random person can create something that will make millions of people angry if it breaks!

Regardless of how you see this dynamic, it is pretty clear that it can create disincentives for individuals (and small groups) to strive for success in open source software. While companies like Tidelift are working to help solve this problem, being aware of the problem - and wary of how the problem might impact you - is far from failing to understand the spirit of open source software. In fact, it may be an incredibly clear-eyed understanding of how the spirit of open source software interacts with the reality of open source software. Furthermore, framing concerns about that dynamic as a social objection instead of a legal objection seems deeply within the spirit of open source software.

As a related community, this type of creator burden is something that the open source hardware community should be aware of and work to address. At the same time, I am not convinced that it is exactly the same type of problem in hardware as it is in software. To the extent that open source hardware includes open source software the problems are essentially identical. However, it is different when applied to the hardware itself.

That difference rests in the fact that design and distribution of software is collapsed into a single step - just post it to the repo. In hardware those steps are quite distinct. Designing open source hardware is quite separate from distributing actual pieces of hardware. That may make it harder for a single person to be responsible for maintaining a piece that is incorporated into millions of projects without any sort of support. But that’s another blog post for another day. Even if the dynamic is not identical, it is certainly similar enough to think about and try to avoid in open hardware.