Today the Engelberg Center released a report from the Open Hardware Distribution & Documentation Working Group that explores what is really needed to create a distributed manufacturing network for open hardware. You can find the official launch post here and the report itself here. I recommend checking it out.

This post focuses on one part of the report: the idea of “Commercialization-as-a-Service.” For me, this was the most intriguing thing to come out of the year’s worth of discussion within the Working Group (and it was a discussion full of intriguing things!).

Open source hardware is constantly working by analogy to open source software, so let’s start there. With open source software, the manufacturing and distribution layer is fairly straightforward and so lightweight that it is easy to miss. Publishing code online effectively manufactures and distributes it worldwide.

Admittedly, in reality the “it just happens” nature of open source software distribution breaks down pretty quickly. Nonetheless, “pretty quickly” is not immediately. The ease of code distribution online means that a piece of open source software can get at least moderate use and build a decent sized community without being supported by significant commitments to building out infrastructure.

That is not really the case with open source hardware. While it is true that you can easily post design files for hardware online, design files for hardware are not hardware. In order to get beyond a relatively small core of people who will assemble and build their own version of the hardware based on instructions, developers of open source hardware are likely to confront a need to begin packaging physical objects and distributing them to others. These objects might take the form of a kit that others assemble, fully constructed hardware, or something else entirely.

Regardless of what form it takes, this manufacturing and distribution layer becomes an independent obligation for the team much earlier in the hardware lifecycle than it would in the software lifecycle. Furthermore, this layer is probably further from the work of designing the hardware than the equivalent responsibility is from writing software. That means that there is no guarantee that the team that originally came together to design and build the hardware has someone (or a group of someones) who are also excited about spinning up a manufacturing and distribution network. That is especially likely to be true in the context of research lab-developed hardware (which is the focus of the paper).

Where does that leave things? Manufacturing and distribution of open hardware becomes an important stand-alone task early in its development cycle. At the same time, the team working to create that hardware may not be excited about engaging in that task.

Enter Commercialization-as-a-Service

One way to try and solve this problem is to get more people excited about building out manufacturing and distribution networks. An alternative approach would be to make open hardware projects less reliant on building their own manufacturing and distribution networks in order to succeed.

This second option may be most realistic in situations where open hardware has been developed in scientific research lab contexts supported by grant funding. In those situations, a grantor has already paid for the development of the open source hardware in the context of the specific project. Currently, in most situations that hardware either remains within the developing lab or is effectively abandoned.

Creating commercialization-as-a-service could make it much more likely that open hardware developed in one lab becomes available to the research community more broadly. That service layer could develop a standing network of international manufacturing and distribution partners, as well as expertise in productization and marketing of hardware. It would work as a pump, pulling proven hardware out of labs and pushing it to other researchers worldwide. In doing so, it would reduce the current ‘unicorn’ condition of academic open hardware success, whereby a successful open source hardware project needs a team that happens to combine the engineering skills to develop the hardware and the logistics skills to manufacture and distribute it.

Building this layer feels like the accelerant role that foundation and other grantors are well positioned to play. Assembling the expertise required to productize, manufacture, and distribute hardware can be done once and applied to a range of hardware. Doing so could greatly increase the impact and adoption of the hardware that funders are already funding. Conversely, without building this layer, these funders are making it much more likely that effective hardware remains tucked into individual labs, hidden from the rest of the research community.

Of course, this is just one of the things that’s in the new report. You can read the entire thing here.

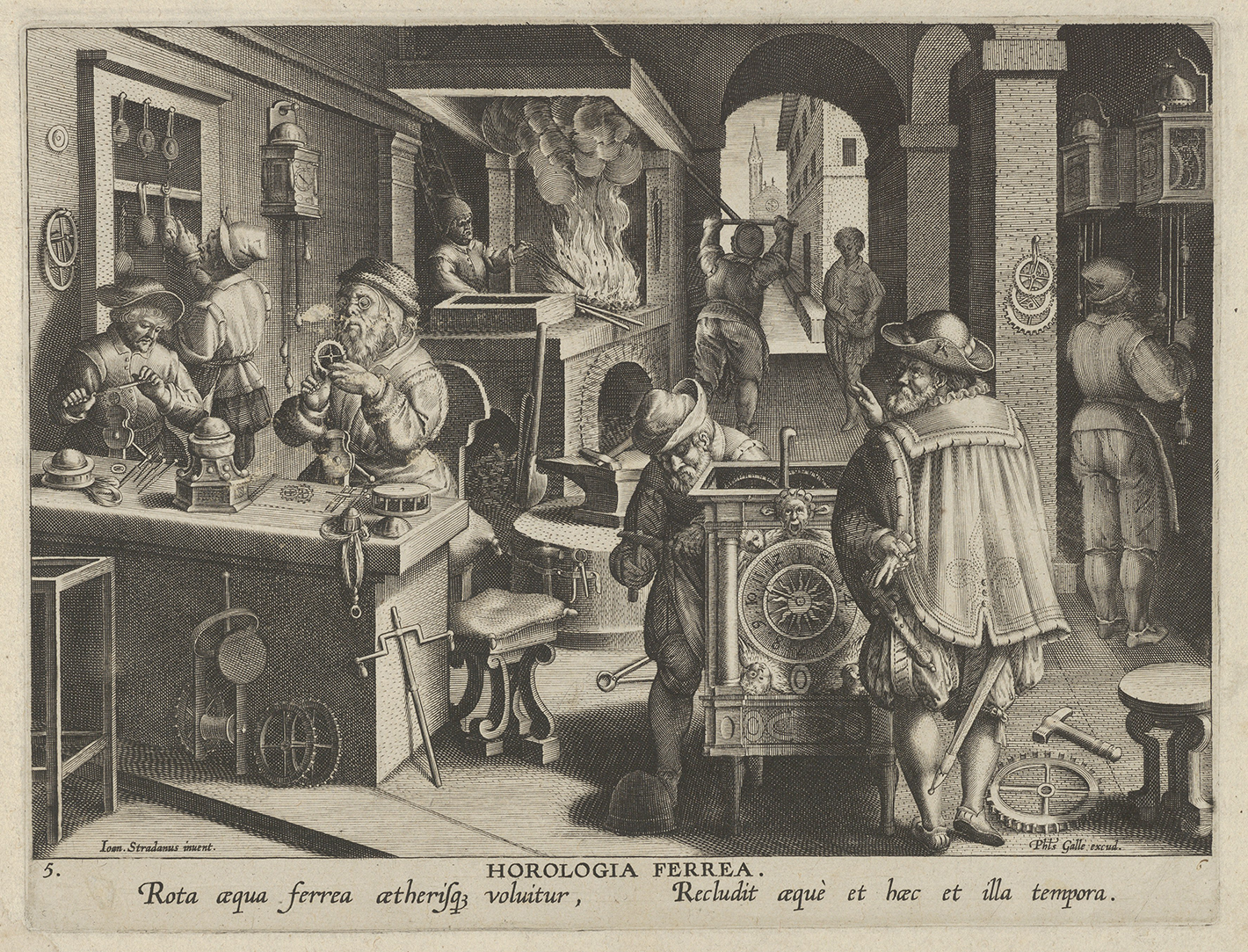

Header image: New Inventions of Modern Times, The Invention of the Clockwork, plate 5, from the Met’s Open Access collection.