This post originally appeared on the Engelberg Center blog.

This is a story of how Spotify’s sophisticated copyright filter prevented us from explaining copyright law.

It is strikingly similar to the story of how a different sophisticated copyright filter (YouTube’s) prevented us from explaining copyright law just a few years ago.

In fact, both incidents relate to recordings of the exact same event - a discussion between expert musicologists about how to analyze songs involved in copyright infringement litigation. Together, these incidents illustrate how automated copyright filters can limit the distribution of non-infringing expression. They also highlight how little effort platforms devote to helping people unjustly caught in these filters.

The Original Event

This story starts with a panel discussion at the Engelberg Center’s Proving IP Symposium in 2019. That panel featured presentations and discussions by Judith Finell and Sandy Wilbur. Ms. Finell and Ms. Wilbur were the musicologist experts for the opposing parties in the high profile Blurred Lines copyright infringement case. In that case the estate of Marvin Gaye accused Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams of infringing on Gaye’s song “Got to Give it Up” when they wrote the hit song “Blurred Lines.”

The primary purpose of the panel was to have these two musical experts explain to the largely legal audience how they analyze and explain songs in copyright litigation. The panel opened with each expert giving a presentation about how they approach song analysis. These presentations included short clips of songs, both in their popular recorded version and versions stripped down to focus on specific musical elements.

The YouTube Takedown

After the event, we posted a video of the panel on YouTube and the audio of the panel in our Engelberg Center Live! podcast feed. The podcast is distributed on a number of platforms, including Spotify. Shortly after we posted the video, Universal Music Group (UMG) used YouTube’s ContentID system to take it down. This kicked off a review process that ultimately required personal intervention from YouTube’s legal team to resolve. You can read about what happened here.

The Spotify Takedown

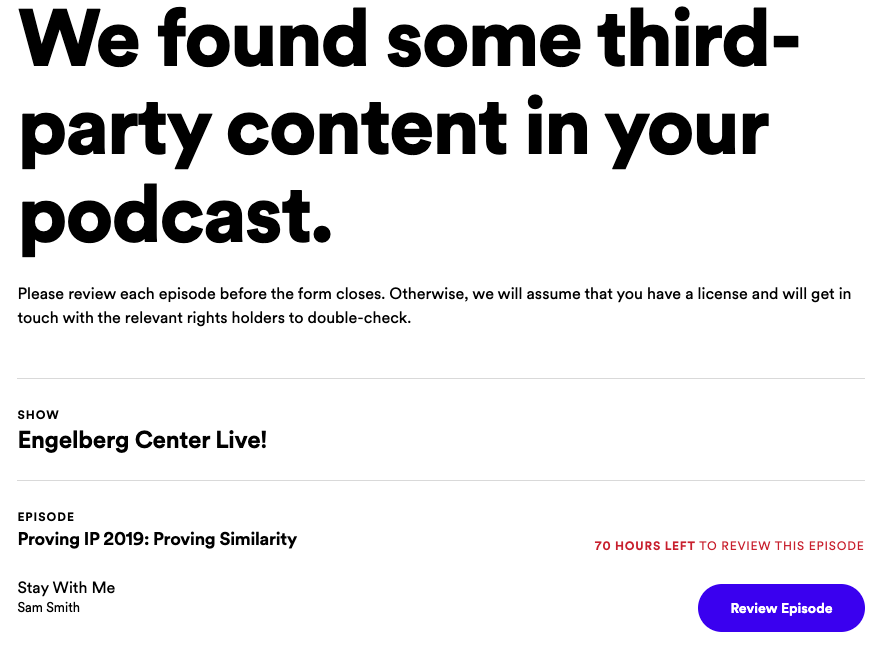

A few months ago, years after we posted the audio to our podcast feed, UMG appears to have used a similar system to remove our episode from Spotify. On September 15, we received an email alerting us that our podcast had been flagged because it included third party content (recall that this content is clips of the songs the experts were discussing analyzing for infringement)

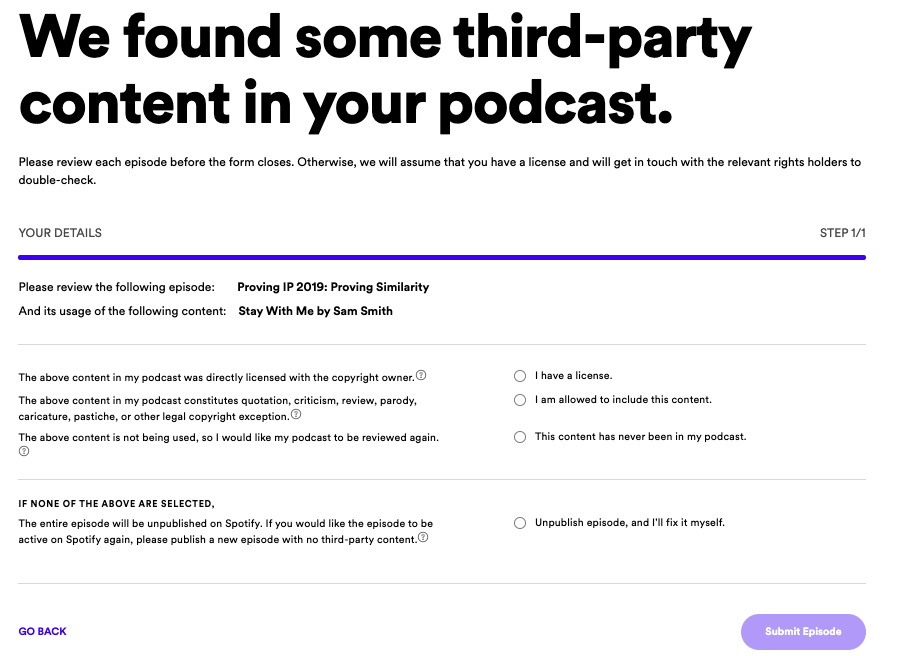

Using the Spotify review tool, we indicated that our use of the song was protected by fair use and did not need permission from the rightsholder.

We received a confirmation that our review had been submitted and hoped that would be the end of it.

The Escalation

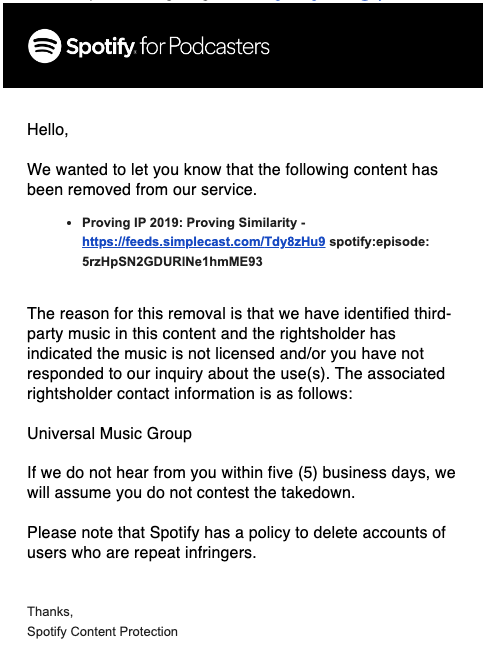

That was not the end of it. On October 12th, we received an email from Spotify that they were removing our episode because it was using unlicensed music and we had not responded to their inquiry.

The first part was true - we had not obtained a license to use the music. This is because our use is protected by fair use and we are not legally required to do so. The second part was not true - we had immediately responded to Spotify’s original inquiry. We immediately responded to this new message, noting that we had responded to their initial message, and asking if they needed anything additional from us.

Spotify Tries to Step Away

Four days later, Spotify responded by indicating that this was now our problem:

The content will remain taken down from the service until the provider reaches a resolution with the claimant. Both parties should inform us once they reach a resolution. We will make the content live upon the receipt of instructions from both parties and any necessary updates. If they cannot reach a resolution, we reserve the right to act at our discretion. The email address we have for the claimant is [redacted].

This is probably where most users would have given up (if they had not dropped off well before). However, since we are the center at NYU Law that focuses on things like online copyright disputes, we decided to push forward. In order to do that, we needed more information. Specifically, we needed the original notice submitted by UMG.

Why the Nature of the Notice is Relevant

We needed the original notice from UMG because our next step turned on the actual form it took.

Many people are familiar with the broad outlines of the notice and takedown regime that governs online platforms. Takedown actions initiated by rightsholders are sometimes called “DMCA notices” because a law called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (or DMCA for short) created the process. While most of the rules are oriented towards helping rightsholders take things off the internet, there is a small provision - Section 512(f) - that can impose damages on a rightsholder who misrepresents that the targeted material is infringing (this provision was famously litigated in the “Dancing Baby” case).

In other words, the DMCA includes a provision that can be used to punish rightsholders who send baseless takedown requests.

We feel that the use of the song clips in our podcast are exceptionally clear examples of the type of use protected under fair use. As a result, if UMG ignored the likelihood that our use was protected by fair use when it filed an official DMCA notice against our podcast, we could be in a position to bring a 512(f) claim against them.

However, not all takedown notices are official DMCA notices. Many large platforms have established parallel, private systems that allow rightsholders to remove content without going through the formal DMCA process. These systems rarely punish rightsholders for overclaiming their rights. If UMG did not use an official DMCA notice to take down our content, we could not bring a 512(f) claim against them.

As a result, our options for pushing back on UMG’s claims were very different depending on the specific form of the takedown request. If UMG used an official DMCA notice, we might be able to use a different part of the DMCA to bring a claim against them. If UMG used an informal process created by Spotify, we might not have any options at all. That is why we asked Spotify to send us the original notice.

Spotify Ignores Our Request for Information

On October 12th, Spotify told us that in order to have our podcast episode reinstated we would need to work things out with UMG directly. That same day, we asked for UMG’s actual takedown notice so we could do just that.

We did not hear anything back. So we asked again on October 23rd.

And on October 26th.

And on October 31st.

On November 7th — 26 days after our episode was removed from the service — we asked again. This time, we sent our email to the same infringement-claim-response@ email address we had been attempting to correspond with the entire time, and added legal@. On November 9th, we finally received a response.

Spotify Asks Questions

Spotify’s email stated that our episode was “not yet subject to a legal claim,” and that if we wanted to reinstate our episode we needed to reply with:

- An explanation of why we had the right to post the content, and

- A written statement that we had a good faith belief that the episode was removed or disabled as a result of mistake or misidentification

This second element is noteworthy because it matches the language in Section 512(f) mentioned above.

We responded with a detailed explanation of the nature of the episode and the use of the clips, asserting that the material in question is protected by fair use and was removed or disabled as a result of a mistake (describing the removal as a “mistake” is fairly generous to UMG, but we decided to use the options Spotify presented to us).

Our response ended with another request for more information about the nature of the takedown notice itself. That request specifically asked if the notice was a formal notice under the DMCA, and explained that we were asking because we were considering our options under 512(f).

Clarity from Spotify

Spotify quickly replied that the episode would be eligible for reinstatement. In response to our question about the notice, they repeated that “no legal claim has been made by any third-party against your podcast.” “No legal claim” felt a bit vague, so we responded once again with a request for clarification about the nature of the complaint. The next day we finally received a straightforward answer to our question: “The rightsholder did not file a formal DMCA complaint.”

Takeaway

What did we learn from this process?

First, that Spotify has set up an extra-legal system that allows rightsholders to remove podcast episodes. This system does a very bad job of evaluating possible fair uses of songs, which probably means it removes episodes that make legitimate use of third party content. We are not aware of any penalties for rightsholders who target fair uses for removal, and the system does not provide us with a way to pursue penalties ourselves.

Second, like our experience with YouTube, it highlights how challenging it can be for regular users to dispute allegations of infringement by large rightsholders. Spotify lost our original response to the takedown request, and then ignored multiple emails over multiple weeks attempting to resolve the situation. During this time, our episode was not available on their platform. The Engelberg Center had an extraordinarily high level of interest in pursuing this issue, and legal confidence in our position that would have cost an average podcaster tens of thousands of dollars to develop. That cannot be what is required to challenge the removal of a podcast episode.

Third, it highlights the weakness of what may be an automated content matching system. These systems can only determine if an episode includes a clip from a song in their database. They cannot determine if the use requires permission from a rightsholder. If a platform is going to deploy these types of systems at scale, they should have an obligation to support a non-automated process of challenging their assessment when they incorrectly identify a use as infringing.

We do appreciate that the episode has finally been restored. You can listen to it yourself here, along with audio from all of the Engelberg Center’s events on our Engelberg Center Live! feed, wherever you get your podcasts (including, at least as of this writing, on Spotify). That feed also includes a special season on the unionization of Kickstarter, and on the Knowing Machines project’s exploration of the datasets used to train AI models.