The brewing dispute over a (purportedly - more on that below) AI-generated George Carlin standup special is starting to feel like another step in the long tradition of rightsholders claiming that normal activity needs their permission when done with computers.

Computers operate by making copies, and copies are controlled by copyright law. As a result, more or less since the dawn of popular computing, rightsholders have attempted to use those copies to extend their control by eliminating the rights of others.

While you can read a physical book without caring what the publisher thinks, publishers insist that reading an ebook with computer needs a license because ereader software loads the file by making copies. Similarly, although record labels can’t control the sale of used records or CDs, they managed to sue the concept of selling used music with computer out of existence.

In this case, although impressions have probably existed since there was more than one human, the Carlin estate appears to be claiming that “impression with computer” needs special permission from them.

The Carlin Video

The subject of this dispute is a video of a computer generated George Carlin avatar doing an hour of new comedy in the style of Carlin. As framed by Dudsey (the comedy team behind the video), in order to create the new content Carlin was “resurrected by an AI to create more material.” (this “resurrection” is necessary because Carlin died in 2008).

While that framing may turn out to be inaccurate (although arguably artistically important to the purpose of the new work), the release of the video kicked off a week of “AI is coming for us” coverage of various flavors, followed by a lawsuit from the Carlin estate.

Is This New?

While the AI packaging clearly drove discussion around the video, if you step back for a minute it really is just an impression of Carlin. This impression uses computers, but I’m not convinced that changes (or should change) the fundamental reality of the activity. Generally speaking, people don’t get veto rights over their impersonators.

Furthermore, if an intriguing article by Kyle Orland in Ars Technica is correct, it may be more than “basically just an impression.” It might just be “an impression.”

Orland’s take has subsequently been confirmed by the Dudsey team to the New York Times (“‘It’s a fictional podcast character created by two human beings, Will Sasso and Chad Kultgen,’ Del wrote in an email. ‘The YouTube video ‘I’m Glad I’m Dead’ was completely written by Chad Kultgen.’”), although the same article reports that the Carlin estate continues to be skeptical of the video’s origin (which makes sense because, somewhat ridiculously, the viability of their entire claim may turn on the distinction).

Orland digs into the Dudsey team and their podcast to provide facially compelling evidence that the content of the special is just a regular old impersonation of Carlin. He even pulls what he describes as an “if I did it” quote from Dudsey podcast that accompanied the video describing how the jokes “could” have been created without sophisticated AI:

Clearly, Dudesy made this, but anyone could have made it with technology that is readily available to every person on planet Earth right now.

If you wanted to make something like this, this is what you would do: You would start by going and watching all of George Carlin’s specials, listening to all of his albums, watching all of his interviews, any piece of material that George Carlin has ever made. You would ingest that. You would take meticulous notes, probably putting them in a Google spreadsheet so that you can keep track of all the subjects he liked to talk about, what his attitudes about those subjects were, the relevance of them in all of his stand-up specials.

You would then take all of his stand-up specials and do an average word count to see just how long they are. You would then take all that information and write a brand new special hitting that average word count. You would then take that script and upload it into any number of AI voice generators.

You would then get yourself a subscription to Midjourney or ChatGPT to make all the images in that video, and then you would string them together into a long timeline, output that video, put it on YouTube. I’m telling you, anyone could have made this. I could have made this.

When framed this way, the whole thing starts to feel like a fairly vanilla impression. Which is how the video presents itself, opening with a disclaimer that ““what you’re about to hear is not George Carlin,” going on to compare itself to an impersonation “like Will Ferrell impersonating George W. Bush”.

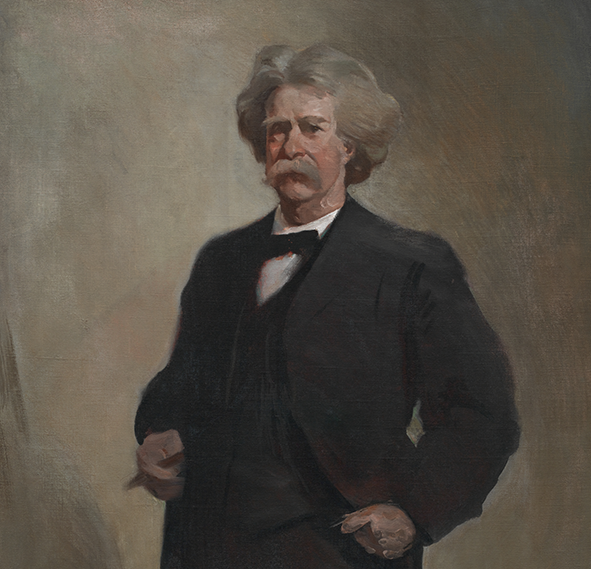

Does the fact that the video includes a representation that is visually similar to Carlin change that analysis? It doesn’t in the physical world. As Brandon Butler quipped on Mastodon “Nobody tell the folks freaking out over the George Carlin special about the Hal Holbrooke Twain show.”

But the Carlin avatar in the video isn’t just someone dressed up like George Carlin! It is an animated version of him!

There’s nothing new about animated impressions either. This random wiki lists 317 celebrity caricatures from Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons. The 1941 short Hollywood Steps Out alone contains dozens.

All of which is to say, doing an impression of someone is not new and does not require that person’s permission. Should doing the impression with a computer upend that?

The Carlin Estate Lawsuit

The Carlin estate lawsuit includes a lot of rhetoric against the video (“Defendants must be held accountable for adding new, fake content to the canon of work associated with Carlin without his permission (or that of his estate).”) and claims of harm from Carlin’s daughter Kelly (“My dad spent a lifetime perfecting his craft from his very human life, brain, and imagination. No machine will ever replicate his genius.”) that could be applied just as easily to any Carlin impression.

The suit also includes claims of violations of California’s Right of Publicity statutes, as well as copyright infringement.

While I think this discussion around copyright, AI training, and AI output is super interesting, I’m not going to be into them in this post. For the purposes of this post, the important thing is that the lawsuit contains the copyright claim at all.

Impression with Computer

The copyright angle only exists because a computer (might be?) involved in creating the new routines. If the new routine was created using Dudesy’s “if I did it” method: “watching all of George Carlin’s specials, listening to all of his albums, watching all of his interviews, any piece of material that George Carlin has ever made,” the Carlin estate would not have any copyright claim to bring, because thinking about things you have read and watched are not activities that rightsholders traditionally get to control

But because this impression does (may?) use computers, it becomes another example of a rightsholder trying to turn “they used a computer” into “I get to control this activity.” If you are someone (like me) who has traditionally been wary of these arguments, this seems like an important time to maintain that skepticism. Even in discussions related to AI.

Header image: Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain) from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery