It feels like any time I have a conversation about attributing data used to train AI models, the completely understandable impulse to want attribution starts to break when confronted with some practical implementation questions.

This is especially true in the context of training data that comes from open communities. These communities rely on some sort of open license that requires attribution (say, CC BY or MIT), and have been built on a set of norms that place a high value on attribution. Regardless of whether or not complying with the license is legally required in these scenarios, many members of the community view attribution as a key element of its social contract.

Since is already solving a number of problems in these communities, it is not hard to imagine a situation where attribution could solve some additional social and political problems related to the growth of these models. These problems tend to be most acute around LLMs and generative AI, but are also relevant to a broader set of AI/ML models.

This post is my attempt to describe some of the practical implementation issues that come to mind when talking about attribution and AI training datasets. It is not intended to be a list of things that advocates for attribution “must fix” before attribution makes sense, or a list of reasons why attribution is impossible. It also is not intended to advocate for or against the value or legal necessity of attribution for AI training data.

Instead, it is a list of things that I would like to figure out before being convinced that attribution is something worth pursuing. At the end, it also flags one lesson from existing open source software licensing that makes me somewhat more skeptical of this approach.

The Simple Model

Let’s start with the simple model of how large, foundational models are trained.

If you wanted to train one of these models, you might start with something like Common Crawl, a repository of 2.7 billion web pages, or LAION-400-Million, a collection of 400 million images paired with their captions. You could throw these datasets into the pot with millions of dollars of computational power, plus some time, and get your very own AI model (again, this is the simple model of how all of this works).

You know all of the data and datasets you used to train the model, so when you release the model you include a readme.txt file that has 3 billion or so entries listing all of the sources you used. Problem solved?

What Works About This Approach

You have given attribution! Each bit of information you used to train the model is right there in the list, alongside the 3 billion other things that went into the pot.

What Doesn’t Work About This Approach

Maybe this solves the problem? Or maybe not?

Everything maps to everything

One problem with this approach is that an undifferentiated list of all of the training data might not be the kind of attribution people are looking for. On some level, if you are training a model from scratch, every data point contributes equal to the creation of that model and every given output of the model.

However, it is also easy to come to an intuitive belief that some data might be more important than others when it comes to a specific output (there are also more quantitative ways one might come to this conclusion). Also, what if it is possible to have a model unlearn a specific bit of data and then continue to perform the same way it performed before unlearning that bit of data? If your model starts generating poetry, the training data that is just a list of calculus problems and solutions might feel less important than pages of poems.

Does that mean that your attribution should prioritize some data points over others when it comes to specific outputs? How could you begin to rank this? Is there a threshold below which something shouldn’t be listed at all? Is there a point where some training data should get so much credit that it gets some sort of special recognition? Would you make this evaluation on a per-model basis, or on a per-output basis?

Is this meaningful attribution?

Being listed as one of 3 billion data points used to train a model is attribution in a literal sense, but is it attribution in a meaningful sense? Should that distinct matter?

The Creative Commons license requires that a licensor give “appropriate credit,” which is defined mostly in the information it contains, not the form that attribution takes. The CC Wiki contains further best practices for attribution, while being upfront that “Because each use case is different, you can decide what form of attribution is most suitable for your specific situation.”

Regardless of whether or not the 3 billion line readme.txt file is legally compliant with a CC license, there may be a significant number of creators who feel that it does not meaningfully address their wishes. Of course, it will also always be impossible to address the wishes of all 3 billion creators anyway. To the extent that attribution is a social/political solution instead of a legal solution, not addressing the wishes of some critical mass of those creators will significantly reduce its utility. Open Future’s Alignment Assembly on AI and the Commons is interesting to consider in this context. Regardless, if listing people in a 3 billion line file does not meet the expectations of a critical mass of people, is it worth imposing as an expectation?

There is a similar, yet also somewhat distinct, version of this question when it comes to open source software. Under most open source software licenses, attribution is including specific text in a file bundled with the code. However, as discussed more at the end of this post, even that can be of questionable utility at scale.

Is this just a roadmap for lawsuits?

Is disclosing everything you used to train your model just a roadmap for lawsuits? This question is a bit harder to answer. IF training models require the permission of the rightsholder AND the 3 billion entry readme.txt does not meet a permissive license’s attribution requirements, then training on data that requires attribution without providing that attribution is infringement. But that’s a big IF.

If it is fair use to train AI models on unlicensed data, listing the training data won’t be a roadmap for lawsuits because creators don’t have a copyright claim to bring against trainers.

Also, current experience suggests that lawsuits aren’t waiting for this particular roadmap anyway.

That means that the roadmap question may be best answered by examining the underlying fair use question, not by weighing the value of attribution. And the fair use fate of AI training is probably much more relevant to it than the attribution compliance question. So I’m going to call this concern both worth flagging and out of scope of this post.

The More Complicated Models

The simple model is just that - a simplified way of thinking about model training. Some of the things that happen in real-world training further complicate things (for a great illustration of many of these relationships, check out Christo Buschek & Jer Thorp’s Models All The Way Down).

Models Trained by Models

As these models are trained on large datasets, it probably should not come as a surprise that trainers are using other AI models to structure, parse, and prepare datasets before they are used to train the model. These structuring, parsing, and preparing models are contributing to the final output model, at least in some ways.

Should the attribution for the final model include all of the data used to train those models as well? Should it differentiate between data used to train the “helper” models and the primary models? How recursively should that obligation extend? What should it mean if the users of the trainer models do not have access to the data used to train those models?

Models Tuned by Models

Large, foundational models are now being tuned to do all sorts of specific tasks. This tuning can include building on an open model like Llama, or importing your own dataset to build a custom RAG.

In cases like this, should attribution include all of the data from the foundational model, plus all of the customized training data? If someone is doing their own tuning without access to a complete list of the training data, is releasing the list of the data they used enough? Should tuning a model built on attributed data create an obligation to release your own tuning data?

Models Optimized by People Who Built Other Models

To me, this is one of the most conceptually interesting situations, and one that highlights the various ways that “learn” is used in these conversations.

The first two scenarios in this section describe some sort of direct lineage between models. However, there are also less direct, more human-mediated linkages. If a team builds model A, they will bring whatever they learned in that process to building model B. That’s true even if model A isn’t “used” to build model B in some sort of literal sense. Should they still attribute the data they used to gain the human knowledge from building model A in the release notes for model B?

This is not a hypothetical scenario. For example, OpenAI describes a “research path” linking GPT, GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT4, explaining that they take what they learn in developing each model and apply it to the next one:

A year ago, we trained GPT-3.5 as a first “test run” of the system. We found and fixed some bugs and improved our theoretical foundations. As a result, our GPT-4 training run was (for us at least!) unprecedentedly stable, becoming our first large model whose training performance we were able to accurately predict ahead of time.

If your data was used to create GPT-3.5, which taught OpenAI something about training models that allow them not to have to use your data to train GPT-4, have you still made a creditable contribution to GPT-4? How far back should we follow this chain of logic?

Lessons Learned from Open Source Software

AI is not the first time that open communities have had to wrestle with the limits of attribution requirements, or with long, nested attribution documents. While there are examples of these across open communities, the most relevant examples probably come from open source software.

Software is made of other software. Most pieces of software contain a number of other pieces of open source software with licenses that require attribution. In practice, this takes the form of super long text files tucked into software releases.

As Kate Downing points out, the value of the attribution requirement in modern software seems to be pretty low. Software may come with pages and pages of attributions that comply with the license requirement (Downing links to a not-particularly-unique example where the attribution document is 15,385 pages long), but it is unclear if the existence of that document is much more than a compliance chore for a responsible maintainer.

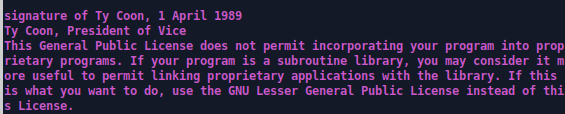

To give another illustration of how long and recursive these documents can be, while drafting this post I also had to update the bios on my printer. The tool I was using required me to agree to the license, and then listed what would have been many pages of attribution. This happened to be the last attribution listed (and therefore the only one I actually saw):

How important is the attribution requirement to Ty Coon, President of Vice and creator of some component of my printer driver update utility? Hard to say. update 7/15/24: as pointed out by Luis Villa on mastodon, Ty Coon is in the sample attribution statement at the bottom of earlier versions of the GPL. This occasionally creates confusion outside of this blog. The one snippet of the code I saw when using the utility was not even the (fake) name of one of its many contributors - it was just the end of the appendix to the license they used, pushing their actual name outside of my terminal window.

Given this history, would it be productive to import this practice into training AI models? I’m skeptical.

update 7/17/24: Back in 2016, Luis Villa also wrote a series of blog posts about a very similar attribution problem that argued against trying to use copyleft for databases. If you made it this far, they are very much worth checking out, because most of those problems reappear in the context of AI.

Hero Image: Pidgeon Hole. A Convent Garden Contrivance to Coop up the Gods