Disclaim and Request: A Way Forward For Creative Commons and 3D Printing?

This post originally appeared on the Shapeways blog.

Unofficial rendering of a request logo.

My earlier post about the 2017 Creative Commons Summit took stock of the complicated relationship between Creative Commons and the 3D printing community, and the fundamental challenge created by Creative Commons (CC) licenses, which are sometimes meant to be legally binding and sometimes used as non-binding social signals.

Perhaps the most intriguing way to address this challenge was an idea put forward by CC USA’s Meredith Jacob for an approach called Disclaim and Request. The idea is to remove ambiguity around the copyright status of objects by using two symbols: the Creative Commons public domain dedication tool CC0 (that’s the disclaim part) and either a new CC tool or other standard notation to request conditions such as attribution or no derivatives.

A CC REQ logo would clarify that the designer is making a request rather than a legally enforceable demand. In other words, they are only using CC as a social signal.

Disclaim

Because 3D printed works can have both artistic (protected by copyright) and functional (not protected by copyright) elements, they have a complicated relationship with copyright. Between works fully protected by copyright and works that are in no way protected lies a spectrum of works with all kinds of partial copyright protection.

Oftentimes that partial protection would not be enough to prevent a bad actor from copying the core of the object in a way that ignores the conditions of the copyright license. That means a traditional CC license would not end up imposing any enforceable obligations on someone who wanted to avoid the conditions of the license.

However, there could be enough copyright protection to make it hard for a good actor to easily make use of the design without a license. The absence of a clear license would then prevent others from building on the work in a way the creator might support. But there is a constant threat that a conditional license could end up overstating its legal control over the object itself.

In these cases, there is no CC license that can prevent what creators view as bad uses while at the same time avoiding erecting unintentional barriers (in the form of conditions that may baselessly scare away a user) to what creators view as good uses. This is not an ideal outcome.

Additionally, the scope of copyright protection can evolve over time. An object that is beyond the scope of copyright when it is created may be pulled into copyright by subsequent judicial decisions or changes to the law.

A perfect tool to resolve this ambiguity would make it clear that the work is available in the commons without imposing conditions that might either be unenforceable or barriers to good actors.

CC0 is that tool. In this context, using a CC0 license effectively says: I do not think there is anything here that is protected by copyright. However, to the extent that copyright does protect part of this design, I waive those rights.

Affirmatively placing an object in the public domain is the most effective way to clarify the copyright status of the object. While you could use a more traditional CC license (such as a CC BY), the conditions of that license (the BY) assume copyright protection that may not exist. In contrast, CC0 waives all copyright interests without attempting to impose unenforceable conditions if those interests never existed in the first place.

Request

Even when a designer has formally disclaimed any copyright interest with CC0, they may still want to take advantage of the social signals that CC licenses can provide. They might want to ask for attribution, for example, even if they know that request is not legally enforceable.

While a traditional CC license might send those signals, using it only to signal creates all sorts of problems, as I explained in the previous post.

That is where a new CC REQ icon comes in.

Unofficial rendering of a request logo.

CC REQ is meant to communicate two concepts to downstream users:

- that the creator does not believe that they have a legally enforceable copyright interest in the work, but to the extent they exist residually they are disclaimed

- that future users nevertheless should comply with the social norms that have grown up around various CC licenses

While these messages could theoretically be folded into a single icon, combining CC0 with CC REQ makes it clear that creators may be actively waiving any existing copyright protection — an idea that should not be hidden in legal fine print.

Why Would This Work?

Disclaim and request achieves two important goals. First, it clarifies the copyright status of the covered work. In a world of copyright ambiguity, this clarity can be incredibly valuable. In the long term, it is better to have people occasionally give away niggling bits of copyright protection than to occasionally claim copyright control that does not exist. This is because those niggling bits are unlikely to serve as barriers against bad users, but overclaiming rights can freeze out legitimate uses.

Second, disclaim and request maintains the signal communicated by a CC license without undermining its enforceability, allowing good actors to understand and comply with the wishes of creators without overstating the authority that those creators have to enforce those wishes. It further clarifies the rules for everyone, which is something that CC has traditionally excelled at.

What’s Next?

For now, disclaim and request is just a proposal. Creative Commons does amazing work every day with limited resources, which means that it needs to prioritize which projects to focus on. Even in a world of unlimited resources, there is also an argument to be made that CC REQ complicates instead of clarifies the status of the CC licenses by adding yet another icon to the set.

All of which is to say that it is up to Creative Commons what to do with this idea.

In light of that, we very much appreciate CCs engagement with these challenges thus far. We hope to continue the discussion, which includes discussions with all the communities involved. As those discussions evolve we will do our best to document them here on the blog.

Read More...The Complicated Relationship Between Creative Commons, Copyright, and 3D Printing

This post originally appeared on the Shapeways blog.

Jane Park at the Creative Commons Global Summit 2017 by Sebastiaan ter Burg CC BY 2.0

The relationship between Creative Commons and the 3D design community is deep and complicated. Last month’s Creative Commons Summit in Toronto provided an opportunity to celebrate the depth and … work on the complications.

Creative Commons was originally conceived with traditional copyright-eligible works like photographs, music, and books in mind, assuming that the works licensed by a Creative Commons (CC) license would clearly be eligible for copyright. The 3D printing design community has integrated CC licenses from its early days, even though copyright does not always apply as cleanly to 3D designs. This organic and somewhat unexpected pairing has lead to a vibrant culture of sharing and collaboration in the 3D design community. It has also raised a number of surprisingly thorny copyright questions.

Fortunately, at least one proposal presented at the Summit would address some of those questions. We’ll outline the proposal in part two of this post, which can be found here.

How We Got Here

Creative Commons has been part of the 3D printing community for years. Thingiverse’s decision to build Creative Commons licenses into the bones of the site helped bring — and sometimes push — countless designers into a sharing community. It also established sharing as an important norm in the 3D design community.

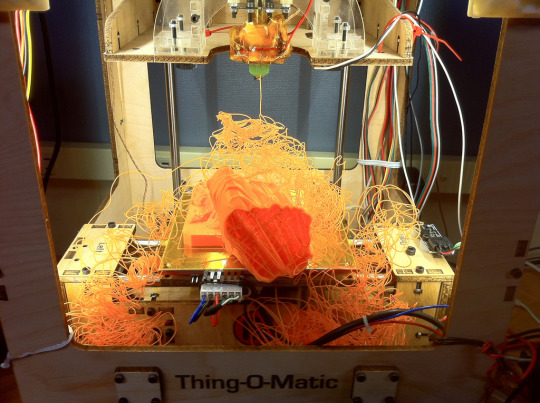

Like 3D printing itself, copyright and 3D printing don’t always align perfectly. Image: Tony Buser CC BY-SA 2.0.

While the ethos of Creative Commons is in close alignment with the beliefs of many 3D designers, the legal realities do not always fit together as cleanly. Creative Commons is a copyright license, but not all 3D printed objects are eligible for copyright protection. That means that a Creative Commons license might not work as expected when it is attached to some 3D printable designs because it might not actually be legally enforceable. Furthermore, conditions that are easy to apply in a digital world (like attribution) can be somewhat harder in the physical realm.

In 2015, Creative Commons held the first formal explorations of the relationship between 3D printing and CC at its Summit in Seoul. That exploration established the foundation for a more detailed discussion last year. With Jane Park and Sarah Pearson guiding the analysis, last year’s discussion helped frame some of the questions that we attempted to answer at this year’s Summit.

3D Printing and Copyright Have a Complicated Relationship

This blog post would be a simple story of two great communities working together except for one challenge: copyright does not apply cleanly in the world of 3D printing. As a result, in the context of 3D printing, licenses based on copyright (such as CC licenses) are not always what they appear. (Pages 4-12 of this white paper explore when copyright does and does not attach to 3D printed files and objects.)

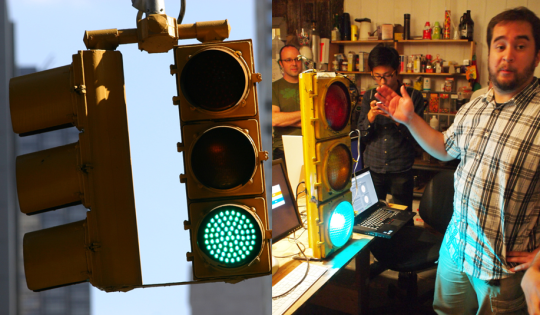

The traffic light on the left creates a legally enforceable obligation to stop at the intersection. The traffic light on the right can only send a social signal to stop doing whatever it is you are doing. Credits: Left image grendelkhan CC BY-SA 2.0. Right image Becky Stern CC BY-SA 2.0. Combined image offered under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Sometimes they exist as legally enforceable licenses. Other times they are merely social signals, requesting that users follow rules that cannot be enforced in court. Oftentimes designers and users are not clear which of those roles apply to any specific model being licensed.

This complicated relationship can create at least two categories of problems if a creator adds a CC license (for example, a CC BY-SA license that requires users to give attribution to the creator and to relicense any adaptations under a similarly open terms) to a model that is not protected by copyright.

Category 1: Damned if you do

First, applying a CC license to a work not protected by copyright shrinks the commons.

By default, a work that is not protected by copyright is in the public domain, available for anyone to do whatever they want with it. No license is required – that’s what the public domain means.

Even if they are not legally enforceable, CC conditions can create barriers to use. Credit: Teresa Alexander-Arab CC BY-ND 2.0.

But some users who want to make use of the public domain model may be prevented from doing so because they do not want to have to comply with the share-alike requirements of the license incorrectly applied to it. Fortunately, since the model is not protected by copyright, that share-alike requirement is not legally enforceable. It is a request masquerading as a demand. Unfortunately, that masquerade may be convincing enough to scare some users away from making completely legitimate uses of the work.

Second, incorrectly using a license can disillusion creators.

This happens when the creator incorrectly believes that the licenses are enforceable for works that are not protected by copyright. A creator could use a CC license to release models online for years. Only after trying to enforce the license would they discover that the condition of attribution baked into that license is unenforceable.

Category 2: Damned if you don’t

Unfortunately, there is also danger in omitting a license when a designer believes that the work is not protected by copyright at all.

If the designer is wrong and the design (or part of the design) is actually protected by copyright, the lack of a CC license will prevent future users from building upon it. This mistake is easier to make than it might appear. Sometimes only small, easily overlooked, parts of models are protected by copyright. Other times copyright law evolves, extending protection to works that were in the public domain when they were created. That means that a creator could be correct about the copyright status of the work when it is created, but wrong by the time a user comes along looking to use it.

Like I said, complicated.

Summit Goals

While Creative Commons ultimately decides how (if at all) it wants to engage with these complicated questions as an organization, the purpose of the sessions at the Summit was to define factors to consider and possibly propose options. Presentations by re:3D, MakerBot (as home to Thingiverse), Aleph Objects, the NIH 3D Print Exchange, and Creative Commons US helped describe current community expectations and propose possible paths forward.

These presentations, especially the one by CC USA’s Meredith Jacob, helped to flag a number of considerations that the community and CC need to keep in mind when trying to address the concerns that prompted the session.

Licenses First, Social Signals Second

Judges need to be able to enforce CC licenses as legally binding documents. Credit: Dark Dwarf CC BY-ND 2.0

CC licenses serve a legal purpose (as a binding legal agreement) and a social purpose (as a social signal to users about how a creator intends for a work to be used). Both of these purposes are important, although they can sometimes work to undermine each other. The key to the long term viability of Creative Commons is to make sure that the social use does not undermine the enforceability of the legal one.

If CC licenses become mere social signals, the legal foundation of Creative Commons begins to erode. That is because courts could decide that creators did not really mean to make their social signal legally enforceable, or that users cannot reasonably be expected to understand that they entered into a real, legally binding agreement when they used a work that was CC-licensed.

That makes it important to ensure that in most cases CC licenses are used in ways that are legally enforceable — as licenses for copyrights that actually exist. Encouraging people to put CC licenses on every 3D printable thing would result in many CC licenses being used in works that are not eligible for copyright protection. In other words, it would result in many CC licenses being used only as social signals. Use primarily as a social signal undermines the enforceability of CC licenses because it undermines the argument that CC licenses are intended to be legally enforceable promises.

Growing the Commons vs. Empowering Sharers

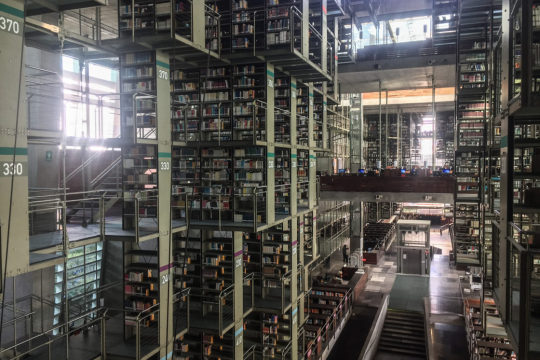

You need to be able to find things in the commons in order to use them. Credit: Paul Keller CC BY 2.0

There is a distinction between a legal commons and a findable commons. The legal commons is made up of works in the public domain (i.e. works not protected by copyright) and works that are permissively licensed with Creative Commons licenses. These are all works that are legally available for people to remix, build upon, and improve without risk.

The findable commons is a smaller subset of the legal commons. It includes works that can legally be shared and found by people who want to remix, build upon, and improve them. The mechanical door opener in your basement or the Renaissance painting in your attic may be part of the legal commons because they are not protected by copyright. But they are not part of the findable commons because other people do not know that they exist.

Convincing people to contribute works already in the legal commons to the findable commons is not a legal challenge. It is a social challenge. It involves making potential contributors comfortable with the idea of contributing to a collective pool of works available to everyone.

The Creative Commons licenses manage to grow the legal commons through the terms of the licenses and to grow the findable commons by allowing people to retain some control over their works. This partial control allows someone to ease into the idea of sharing without having to choose between being fully open or fully closed. Someone who is uncomfortable with the idea of unconditionally contributing their work to the commons might feel more comfortable contributing under the condition that any future users give them credit or that their work is not modified.

This can be true even for people creating works that are in the public domain (and therefore the legal commons) from the start. If they do not realize that the CC license cannot be enforced, the CC license terms may still encourage them to contribute their work that is in the legal commons into the findable commons by creating an illusion of control.

This creates a tension. Educating and empowering users so they understand when a CC license is not enforceable (and therefore drawing attention to the illusion) could also make them less reluctant to contribute to the findable commons. The win for user education could create at least a short-term loss for the commons. While user education is likely the higher good, it is important to recognize the potential short-term cost of its expansion.

Education Helps

At the core of all of these questions is the issue of education. There are 3D printable works that are protected by copyright. There are 3D printable works that are not protected by copyright. If designers and users could learn how to easily distinguish between the two and apply licenses in a legally accurate manner everything would be easy and this blog post would be a lot shorter.

Unfortunately, drawing this distinction can be complicated for specialists (and the U.S. Supreme Court keeps changing the rules). That makes it unreasonable to expect nonspecialists to fully understand the scope of copyright protection and unrealistic to think that we can educate our way out of this problem.

That being said, a better understanding of these issues could go a long way. Creative Commons may be well positioned to help create tools, disclaimers, and other mechanisms to help designers, platforms, and users understand what happens to the Creative Commons licenses as they drift further away from their traditional areas of coverage.

Part 2

So many questions and challenges! Fortunately, part 2 of this blog post discusses a concrete proposal that helps address some of them.

Read More...Regulating DIY Medical Devices

This post originally appeared in Volume 56 of Make Magazine under the headline How to Know if the FDA Wants to Regulate Your Prototype. My contract required me to give them 3 months of exclusivity. With that up, I’m posting it here.

It’s all good fun to 3D print a DNA extraction centrifuge, make a homebrew heart rate monitor, or build an Arduino-powered bioreactor. But as you delve deeper into the world of biohacking, you may eventually wonder if (or when) the government will take an interest in what you’re doing.

There are lots of good reasons for government regulation here. When you take a drug, get a device implanted in you, or have a medical test done, it can be comforting to know that someone is ensuring that the drug isn’t poison, the device won’t explode inside you, and the medical test won’t insist that your ears are falling off (assuming that your ears aren’t actually falling off).

The Spirit of ‘76

For all of their benefits, regulations can also prevent good things from happening. Processes can be expensive to comply with and testing can take time. Small-scale participants can have trouble identifying rules relevant to them, let alone comply with them. That makes regulation, like so many things in life, a balance between safety and doing new things.

Unfortunately for DIY biohackers, the last time Congress passed a major medical device law was in 1976. Back then, only large companies had the ability to manufacture medical devices. Congress didn’t imagine that people would be making them at home. It certainly didn’t imagine that the at-home inventors would be able to distribute them to the world over the internet — and possibly do so without any commercial infrastructure.

Nonetheless, the regulatory structure of 1976 remains in force today. Devices are sorted into three tiers based on their intended use. Class I devices are regulated under “general controls,” which are generally light-touch rules designed to handle lower risk devices. Class II devices are subject to special controls because they are potentially more dangerous. Class III devices require premarket approval before being distributed. (We’re just setting the scene, but if you have specific questions about the three-tier system or about your specific device, you should speak with a lawyer.)

General Wellness vs. Medical

For our purposes, the question is not how medical devices are regulated, but rather when your project becomes a medical device that the FDA wants to regulate. The difference is between a “general wellness” device, which isn’t regulated, and a “medical” device, which is. Distinguishing between them involves two major factors.

The first is if the device is geared towards “general wellness.” The more the device is oriented towards general wellness, the less likely it is to be regulated by the FDA. General wellness is a focus on overall health instead of specific diseases. Think about jogging — it’s a healthy lifestyle choice that impacts a range of diseases, heart disease among them. But jogging isn’t a specific treatment for heart disease in the same way that prescription medication is. General wellness devices tend to measure things like fitness, sleep, concentration, heart rates, or physical impact in order to help you live a healthier lifestyle.

The second factor is whether the device poses a low risk to safety. Not surprisingly, if it doesn’t pose a safety risk, the FDA is more likely to classify it as a general wellness device. Conversely, if a device could pose a significant risk — even due to misuse — the FDA is likely to want to take a closer look. Helpfully, the FDA provides four characteristics to look for in a device, any one of which would suggest that the device poses a higher-than-low risk to safety:

- Is the product invasive (does it penetrate the skin)?

- Is the product implanted?

- Does the product use a technology that is itself risky if not regulated (think medical lasers or radioactive elements)?

- Are similar existing products regulated?

That last point is important. If you are working on a device and all of the established commercial devices in the space are regulated, the FDA will probably take a keen interest in your device as well.

What’s the takeaway here? Keep hacking and building new things. But as you start building devices that are geared toward treating specific diseases or that can do real harm if they malfunction, keep in mind that the FDA might be interested. At that point it is probably time to put down this magazine and find yourself a lawyer.

Learn More

The FDA recently published guidance to help distinguish between medical devices and wellness devices.

Anna Wexler takes a deep dive into the regulations surrounding brain stimulation devices currently on the market (there’s also a longer version that’s behind a paywall). Below is a presentation she gave on the topic:

The challenges posed by DIYers entering the modern medical space has not gone unnoticed by the medical establishment. Doctor Jeremy A. Greene outlines the various concerns with DIY medical devices in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The FDA itself walks through how it approaches some of these questions in section II. B. of this workshop paper on neurodiagnostic devices.

The FDA also provides information about how it regulates medical devices here, here, and here.

Read More...