In response to a number of copyright lawsuits about AI training datasets, we are starting to see efforts to build ‘non-infringing’ collections of media for training AI. While I continue to believe that most AI training is covered by fair use in the US and therefore inherently ‘non-infringing’, I think these efforts to build ‘safe’ or ‘clean’ or whatever other word one might use data sets are quite interesting. One reason they are interesting is that they can help illustrate why trying to build such a data set at scale is such a challenge.

Read More...Carlin AI Lawsuit Against 'Impression with Computer'

The brewing dispute over a (purportedly - more on that below) AI-generated George Carlin standup special is starting to feel like another step in the long tradition of rightsholders claiming that normal activity needs their permission when done with computers.

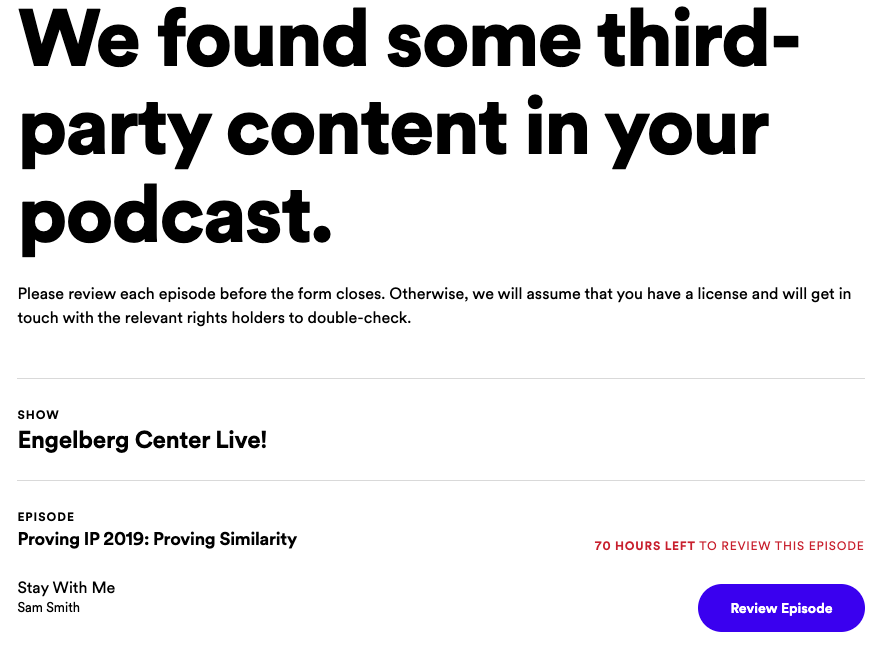

Read More...How Explaining Copyright Broke the Spotify Copyright System

OSHWA Files Brief in Support of Using, Repairing, and Hacking Things You Own

This post originally appeared on the OSHWA blog .

Read More...Powerful ToS Hurt Companies and Lawyers, Not Just Users

I recently found myself reading Mark Lemley’s paper The Benefit of the Bargain while also helping a friend put together the Terms of Service (ToS) for their new startup. Lemley’s paper essentially argues that modern ToS - documents that are written by services to be one sided and essentially imposed on users as a take-it-or-leave-it offer - should no longer be enforced as contracts because they have lost important fairness elements of what make contracts contracts.

Read More...