Late last year we highlighted the fantastic work that the Cooper Hewitt Museum is doing to set an example for how museums and other cultural institutions can make high

quality 3D scans available to the public. Unfortunately, just as long

summer days must turn to cold winter nights, we now have an example of a

different cultural institution doing a fantastic job of setting an

example of how not to handle the same types of issues.

Scene: Sioux Falls, South Dakota

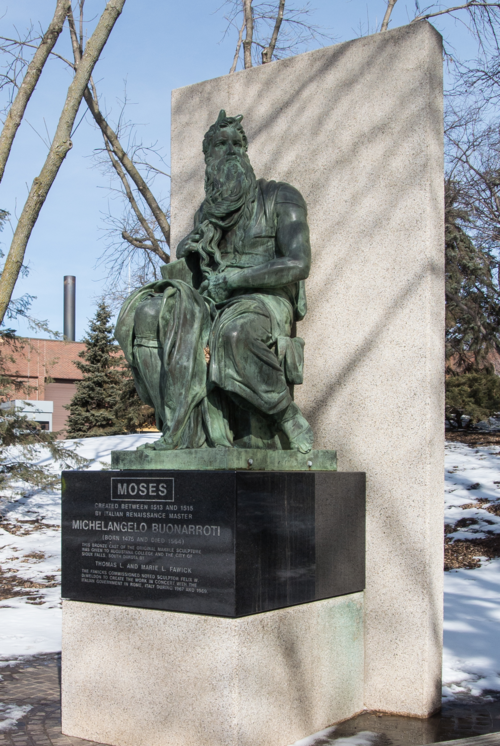

Sioux Falls is home to a high quality cast of Michelangelo’s Moses, one of his best-known sculptures.* The cast itself co-owned by the City of Sioux Falls and Augustana College and is on public display on the campus of Augustana College.

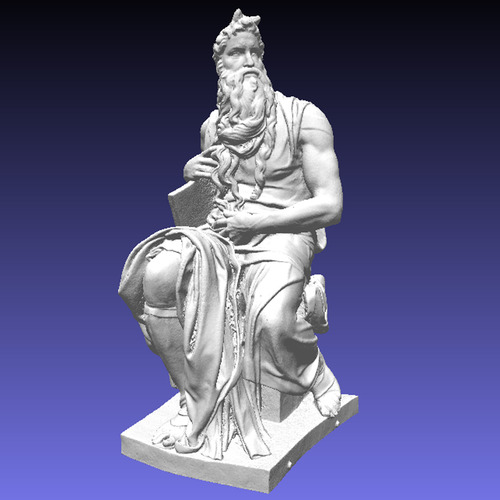

Local photographer Jerry Fisher decided to use the sculpture as his subject while he honed his 3D capture skills, documenting his progress on Twitter and Google +. Unfortunately, this completely reasonable and legal act caught the attention of representatives of Augustana College. Citing an unspecified (and ultimately nonexistent) mixture of copyright and other intellectual property rights concerns, the College asked Fisher to remove his 3D files from the internet. Fearing some sort of liability, Fisher complied with this groundless request, thus depriving himself and everyone else of the opportunity to use the files.

Augustana College’s Request Was Out of Line - The Public Domain is Real

Let’s get one thing out of the way right now: Augustana College had no legal right or basis to threaten Fisher with the specter of infringement. There is no copyright protection for a sculpture that was created at the dawn of the 16th century by a sculptor who died 450 years ago. All of Michelangelo’s work is firmly in the public domain. If fact, copyright didn’t even exist during Michelangelo’s lifetime. From the moment he sculpted his Moses anyone could copy, remix, and build upon it for any reason, without having to ask permission.

Of course, the sculpture in Sioux Falls is not Michelangelo’s original sculpture. The original Moses is still in Italy. The Sioux Falls sculptures are exact replicas made in the early 1970s - exact replicas, it seems appropriate to mention, that were made without permission of Michelangelo’s estate because the originals are not protected by copyright. There was no copyright on the original sculpture, and there is no copyright in the exact copies of the original sculpture.

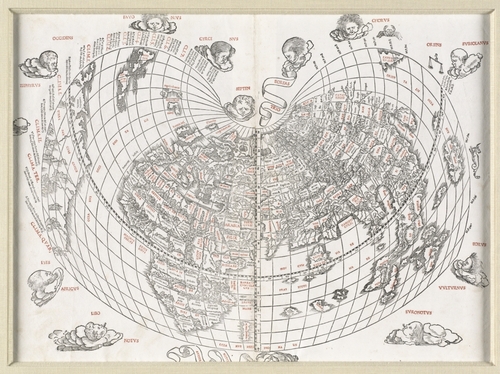

If Fisher were practicing his 3D scanning on original sculptures made in the early 1970s, the sculptures would likely still be protected by copyright. Fortunately for Fisher and everyone else, the sculpture in question is not an original sculpture – it is a copy. Just as scanning a 16th century map doesn’t give me a new copyright in the scan file, casting a copy of a 16th century sculpture doesn’t give me a new copyright in the cast.

The Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at Boston Public Library scanned this 16th century map, but doing so did not give the library a new copyright in their scan

Without a copyright in the original sculpture or the reproduction, there is simply no copyright reason that Fisher shouldn’t be able to make as many scans as he likes. It is irresponsible, and undermines Augustana’s mission to “enrich[] lives by exposure to enduring forms of aesthetic and creative expressions,” for Augustana to suggest otherwise.

3D Scanning is Not Magic

On some level, the college recognizes that they do not have the right to restrict copies of their Moses cast. People take photographs of the sculptures all the time, but the college does not assert an imaginary copyright interest and request that those pictures be destroyed. But somehow, a 3D scan – just as much a copy from a copyright standpoint as a photo - raised novel and inarticulable concerns with College officials. Fortunately for everyone who is not Augustana College, 3D scanning is not magic and does not give Augustana College or anyone else the right to steal works out of the public domain.

How Did This Happen?

In all likelihood, Augustana College was not acting maliciously when they told Fisher to take down the files, and did not realize that they were doing anything wrong. This case has all of the hallmarks of a type of lawyer-itus (or quasi-lawyer-itus), that tends to manifest itself around copyright. Representatives for the College had a vague concern that the scanning might possibly infringe on someone’s copyright or trademark or something, and that somehow the College could be implicated.

When faced with that vague concern, the College essentially had two choices. One was to do some research in order to find out if their concern was actually warranted. The second, and this is the path it appears they took, was to just say no, throw out scary words like “copyright,” shut the project down, and hope that the problem went away.

The second choice is the lazy choice and is almost always easier. It takes almost no time and effort. But it also takes away the public’s right to access public domain works (the same right, it should be noted, that allowed the casts to be made in the first place).

This type of choice between reacting and thinking is one that leaders at cultural institutions all over the country will be facing in the coming years when they start getting questions about 3D scanning. There is always the temptation to say “no” and get on with your day. But the better response is to take the time to really understand the issue and work to keep the sculptures, buildings, and objects that are in the public domain out of a fake copyright fog. Copyright protection lasts long enough – a combination of fear and laziness should not be allowed to pull works out of the public domain.

Bonus: Today’s Copyright Laws Are Designed To Make Lawyers Overly Cautious

Many lawyers are cautious by nature, but there are elements of copyright law that give them an extra incentive to be even more cautious than usual. Specifically, a quirk of copyright law can make monetary damages balloon unusually quickly in infringement cases.

In order to get money in most civil cases you need to show your damages. Get hit by a car? Show the court your medical bills and lost wages. Painter paint your wall hot pink instead of staid beige? Show the court how much it cost you to get the work redone.

Copyright law is different when it comes to damages. A copyright holder can sue for actual damages, just like the person hit by a car or with a bad paint job. But they also have the option to sue for what are called “statutory damages.” Instead of pointing to the actual cost of infringement (that illegal download of a song deprived the artist of $0.99), a copyright holder can just point to an amount that is written into the text of the law to serve as the value of the damages. That amount can be in the six figures for a single infringement (that’s how infringing 24 songs can result in a $1.5 million damages award).

Among other things, the threat of these statutory damages makes lawyers super cautious around potential copyright infringement claims. Even if he was infringing, the actual cost of Fisher making unauthorized copies of the sculpture would likely be no more than a few hundred dollars (if that). Faced with that kind of liability, a lawyer may decide to take a bit of a risk and err on the side of public access. But in the face of hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of liability, a lawyer has to be pretty sure before saying “yes,” even if they start from the assumption that the work is in the public domain. And getting that sure can take a lot of time.

Fortunately, there may be an opportunity to change this. Congress is taking a serious look at updating copyright laws during 2015, and we will be working hard to get statutory damages reduced or eliminated. That will make it easier for people to access works that are in the public domain by significantly reducing the cost of errors. Keep your eyes open for more discussion of this in the coming months.

* It is actually home to casts of two sculptures: Moses and David. While this post focuses on Moses, you can rest assured that the analysis also applies to David.

Statue image credit: Jerry Fisher