(This post originally appeared on the Shapeways blog)

Shapeways designers create a mindboggling array of objects every day. This diversity fosters a vibrant Shapeways community and makes Shapeways shops exciting places to explore. It also means that models on Shapeways can potentially involve a number of different types of intellectual property and other rights.

Sometimes this rich diversity of rights can be a bit confusing and overwhelming. In an attempt to bring a bit of order to the rights chaos, today we’re kicking off a series of blog posts that try to briefly describe a handful of types of rights that might touch upon models on Shapeways. Today’s post will cover the high level basics. Future posts – they’ll be coming up every fortnight or so – will dive a bit deeper into issues raised by these rights. We’ll try to link to all of them from this post in the future so you can find them all in one place.

(If you want a slightly more in depth – but still written for designers who are not lawyers – explanation for how all of these things fit together, you might want to check out these three whitepapers).

((This series is for educational purposes only and is not legal advice. This area of law tends to be maddeningly fact-specific, so if you have a specific question it is always wise to talk to a lawyer who understands your circumstances.))

Copyright

A drawing of a pig dancing with children is protectable by copyright.

If you are familiar with one kind of intellectual property right, it is probably copyright. Copyright is designed to be an incentive to produce artistic, creative things. Here on Shapeways that can mean things like sculptures, figurines, and jewelry. Importantly, copyright generally does not protect functional items like mechanical parts or brackets and connectors (those are the domain of patents, described below).

You do not need to apply for a copyright in order to have copyright protection (although there are advantages to registering – something that you can do here.). As long as the thing you have created is of a type that is eligible for copyright protection, it is protected by copyright from the moment it exists. Copyright protection will generally last for the life of the author plus 70 years after her death. Copyright also allows for independent creation – if two people come up with identical models without copying each other, each one gets their own copyright protection for their model.

Copyright mostly governs the making of copies of a protected item (that’s where the “copy” in copyright comes from). Traditionally this focused mostly on ‘literal’ copying, like making an exact copy of an entire book or origami crane skeleton. However, copyright also governs the creation of ‘derivative’ works. These aren’t necessarily exactly copies, but rather are copies that are derived from some protected work. A classic example of this is creating a “copy” of a book by turning it into a movie. There are important exceptions to these general rules (fair use probably being the best known) that we will cover in future blog posts.

Patent

A dynamo is the kind of invention that is protectable by patent.

Patent is designed to be an incentive to produce “functional” innovations. Contrast this with copyright – those mechanical parts, brackets, and connectors that I said were not eligible for copyright protection are the types of things eligible for patent protection.

Also in contrast with copyright, you do not get a patent automatically just for creating something that is functional and original. You need to apply for a patent in order to get patent protection. If you get it, that patent protection generally lasts for 20 years. Unlike copyright, patent law does not allow for independent creation. That means that once you have a patent, anyone who practices that patent will infringe upon your patent even if they didn’t know about it beforehand.

Generally speaking, someone infringes on your patent by “practicing it” – that is, doing what the patent describes – without your permission.

Trademark

You can trust Aspinall to sell a product that is “absolutely non-poisonous” so look for their trademark on the bottle.

Copyright and patent are both awarded as incentives to create and share innovation. While trademark is often lumped in with copyright and patent as “intellectual property,” its purpose is quite different. Trademark is all about consumer protection. When you see a trademark on a product, that trademark means that the trademark owner stands behind the product.

As a result of this different purpose, trademark rules can feel very different from copyright and patent rules. In copyright and patent, infringement usually comes in the form of copying or using the protected creation. In trademark, infringement is usually judged by a “likelihood of confusion” standard: is it likely that a given use of a trademark would confuse a consumer into thinking that the trademark owner is standing behind the use? Does the use make it seem like the object is from or endorsed by the trademark holder? If so, the use may be infringing on the trademark.

Right of Publicity

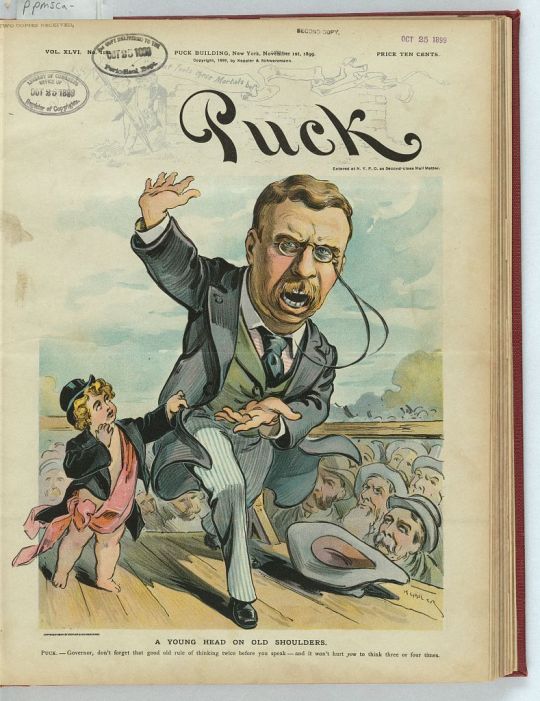

TR might not like it, but as a public, newsworthy figure Puck is not violating his right of publicity even when they use his image to sell magazines.

Right of publicity is also a bit out of the intellectual property mainstream, but it is worth mentioning here. Right of publicity is all about being able to control how your image is used commercially. In the US it is based in the right of privacy. Generally speaking, if you are leveraging someone’s identity for commercial gain you may be infringing on their rights of publicity.

There is at least one noteworthy exception to this general rule. In the United States we don’t want the right of publicity to smother the type of free expression protected by the First Amendment. As a result, the more you are using someone’s likeness to comment on or criticize them – and this is especially true if that someone is a public figure – the less likely you are to be infringing on their right of publicity.

Just an Introduction

This post is designed to be an introduction to some of these concepts and, as a result, just scratches their surface. It leaves a lot of things out that may or may not be relevant to a specific case. Some of those things will be addressed in posts further into this series.

If there are issues that you would like addressed in future posts let me know in the comments or on twitter@MWeinberg2D. We can’t address specific legal disputes, but we can explain how some of these pieces fit together.