A team just announced the release of the Common Pile, a large dataset for training large language models (LLMs). Unlike other datasets, Common Pile is built exclusively on “openly licensed text.” On one hand, this is an interesting effort to build a new type of training dataset that illustrates how even the “easy” parts of this process are actually hard. On the other hand, I worry that some people read “openly licensed training dataset” as the equivalent of (or very close to) “LLM free of copyright issues.”

There is an active fight over whether or not training an LLM on data infringes on the copyright in that data. If the activity is protected by fair use (in the US) the license on the work does not matter because the trainer does not need permission from the rightsholder. If the activity is not protected by fair use, the license on the work matters a lot. The only way to train without infringing would be to do so within the scope of a license (open, closed, or otherwise).

In response to this, there are a number of efforts to build openly licensed datasets. The theory is that, if it turns out that training models requires permission from the data rightsholders, open data comes with that permission built in.

There are a few problems, or at least complications, with this approach. I am not suggesting that the Common Pile team in particular has failed to wrestle with these. Instead, this is a generalized list of problems that have come up across conversions around open training datasets.

- Openly licensed does not mean free from restrictions. Very few open licenses are public domain dedications. At a minimum, most of them require some sort of attribution to the original creator.

- It is not clear what attribution means in the case of LLMs or their outputs. At least conceptually, including attribution information in a dataset is fairly straightforward - it’s just metadata. That is less straightforward when it comes to the models themselves. What does it mean to give attribution to the 2 trillion tokens used to train a model? Attribution is even harder when it comes to outputs. What’s the best way for an output to provide attribution for the 2 trillion tokens involved in training the model that produced it? And these are just the easy cases. These questions get harder the more you think about them.

- Do we even want to import attribution practices into training datasets? The core concept of attribution has proven to be incredibly useful across a range of open communities. However, it may not be the right solution to every problem. I keep coming back to a post by Kate Downing that points out that attribution requirements for open source software does not necessarily scale very well. If we know attribution does not scale well at the scale of open source software, do we want to bring it into the exponentially larger LLM context? Maybe? But also maybe not? It strikes me as a question that deserves more thought before we just assume it makes sense.

If there is not a way to comply with requirements of an open license, is spending time building an openly licensed training dataset worthwhile?

The answer may very well be “yes”. However, I worry that there is a tendency to jump directly from “this is an openly licensed dataset” to “we can use it without worrying about copyright”. At a minimum, there is value in articulating how an openly licensed dataset would interact with a goal of creating a model free from copyright-based constraints. Of course, I’m always going to say that people need to spend more time thinking about the copyright aspects of their work…

Coming back to the Common Pile paper specifically, as I mentioned at the top, it does a great job of showing how even easy things are hard. Faced with the challenge of building an openly licensed dataset, it is intuitive to start with platforms that host a lot of openly licensed content. Section 2 of the paper is all about the traps waiting for you on those platforms. What about people who post things under an open license when they are not the rightsholders? Which licenses count as open? What about collection-level licenses that do not reflect the licensing of the included works?

This stuff is hard enough to do by hand that I wrote a whole blog post about clearing a single image from a training dataset. What should it mean when someone makes the inevitable mistakes at scale? If the dataset has 2 billion tokens, how many not-actually-openly-licensed tokens should spoil the set? 10? 10 million? What if the 10 are owned by Disney?

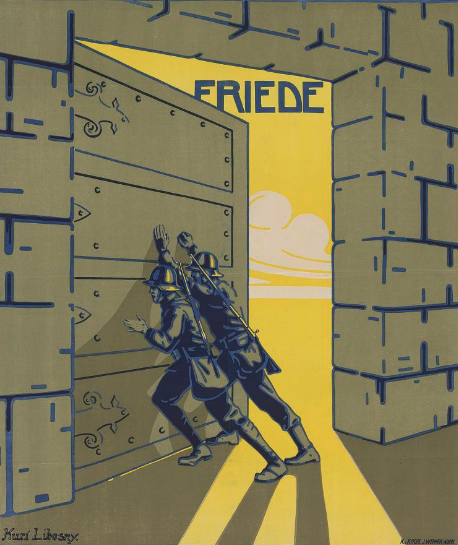

Hero Image: A portion of “Kriegsanleihe” from the Smithsonian Open Access Collection