There have been a fantastically large number of maker and open source hardware responses to the Covid-19 virus. These responses are largely focused on developing stopgap solutions to shortages of medical supplies critical to fighting the outbreak. While there will be a number of lessons to be learned from studying this movement, I want to flag one in this post: the (unexpectedly?) important role that authorities should play in channeling maker energy in important directions. Unfortunately, that role’s importance is becoming clear because authorities have been slow to play it.

Read More...New CERN Open Source Hardware Licenses Mark A Major Step Forward

Earlier this month CERN (yes, that CERN) announced version 2.0 of their open hardware licenses (announcement and additional context from them). Version 2.0 of the license comes in three flavors of permissiveness and marks a major step forward in open source hardware (OSHW) licensing. It is the result of seven (!) years of work by a team lead by Myriam Ayass, Andrew Katz, and Javier Serrano. Before getting to what these licenses are doing, this post will provide some background on why open source hardware licensing is so complicated in the first place.

Read More...How We Made the Open Hardware Summit All Virtual in Less Than a Week

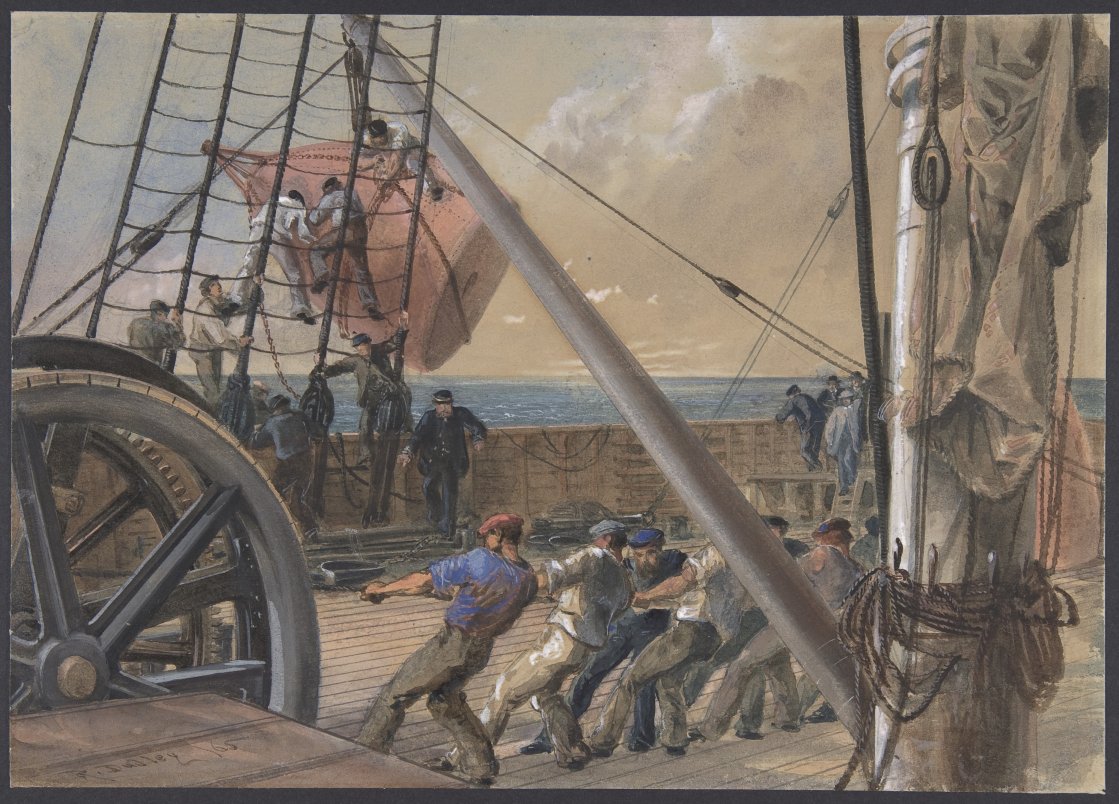

The Smithsonian Goes Open Access

It doesn’t get a lot bigger than this. On February 25th the Smithsonian went in big on open access. With the push of a button, 2.8 million 2D images and 3D files (3D files!) became available without copyright restriction under a CC0 public domain dedication. Perhaps just as importantly, those images came with 173 years of metadata created by the Smithsonian staff. How big a deal is this? The site saw 4 million image requests within the first six hours of going live. People want access to their cultural heritage.

Read More...