This post originally appeared on opensource.com

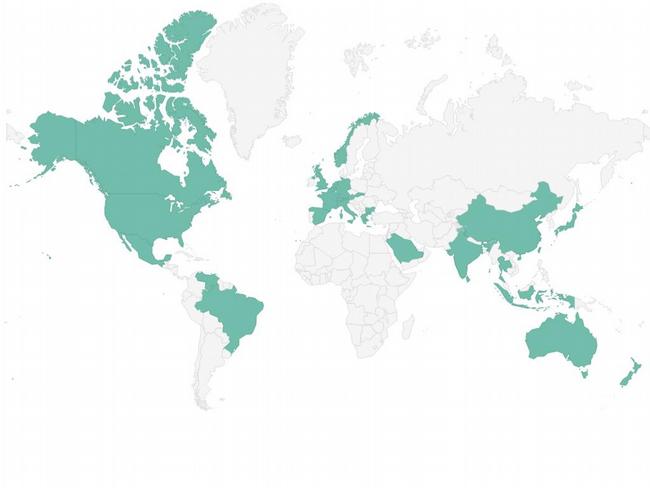

The Open Source Hardware Association’s Hardware Registry lists hardware from 29 different countries on five continents, demonstrating the broad, international footprint of certified open source hardware.

In some ways, this international reach shouldn’t be a surprise. Like many other open source communities, the open source hardware community is built on top of the internet, not grounded in any specific geographical location. The focus on documentation, sharing, and openness makes it easy for people in different places with different backgrounds to connect and work together to develop new hardware. Even the community-developed open source hardware definition has been translated into 11 languages from the original English.

Even if you’re familiar with the international nature of open source hardware, it can still be refreshing to step back and remember what it means in practice. While it may not surprise you that there are many certifications from the United States, Germany, and India, some of the other countries boasting certifications might be a bit less expected. Let’s look at six such projects from five of those countries.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria may have the highest per-capita open source hardware certification rate of any country on earth. That distinction is mostly due to the work of two companies: ANAVI Technology and Olimex.

ANAVI focuses mostly on IoT projects built on top of the Raspberry Pi and ESP8266. The concept of “creator contribution” means that these projects can be certified open source even though they are built upon non-open bases. That is because all of ANAVI’s work to develop the hardware on top of these platforms (ANAVI’s “creator contribution”) has been open sourced in compliance with the certification requirements.

The ANAVI Light pHAT was the first piece of Bulgarian hardware to be certified by OSHWA. Olimex’s first OSHWA certification was for the ESP32-PRO, a highly connectable IoT board built around an ESP32 microcontroller.

China

While most people know China is a hotbed for hardware development, fewer realize that it is also the home to a thriving open source hardware culture. One of the reasons is the tireless advocacy of Naomi Wu (also known as SexyCyborg). It is fitting that the first piece of certified hardware from China is one she helped develop: the sino:bit. The sino:bit is designed to help introduce students to programming and includes China-specific features like a LED matrix big enough to represent Chinese characters.

Mexico

Mexico has also produced a range of certified open source hardware. A recent certification is the Meow Meow, a capacitive touch interface from Electronic Cats. Meow Meow makes it easy to use a wide range of objects—bananas are always a favorite—as controllers for your computer.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia jumped into open source hardware earlier this year with the M1 Rover. The robot is an unmanned vehicle that you can build (and build upon). It is compatible with a number of different packages designed for specific purposes, so you can customize it for a wide range of applications.

Sri Lanka

This project from Sri Lanka is part of a larger effort to improve traffic flow in urban areas. The team behind the Traffic Wave Disruptor read research about how many traffic jams are caused by drivers slamming on their brakes when they drive too close to the car in front of them, producing a ripple of rapid breaking on the road behind them. This stop/start effect can be avoided if cars maintain a consistent, optimal distance from one another. If you reduce the stop/start pattern, you also reduce the number of traffic jams.

But how can drivers know if they are keeping an optimal distance? The prototype Traffic Wave Disruptor aims to give drivers feedback when they fail to keep optimal spacing. Wider adoption could help increase traffic flow without building new highways nor reducing the number of cars using them.

You may have noticed that all the hardware featured here is based on electronics. In next month’s open source hardware column, we will take a look at open source hardware for the outdoors, away from batteries and plugs. Until then, certify your open source hardware project (especially if your country is not yet on the registry). It might be featured in a future column.