Late last week the United States Copyright Office and the Librarian of Congress handed a significant victory to 3D printer users who want to use 3D printing materials of their choice. The Copyright Office and Librarian published a rule that made it clear that using materials from a someone besides the company that manufactures the 3D printer does not violate copyright law. This is a win for anyone who wants to experiment with 3D printers, and for the concept of limitations to the scope of copyright law more generally.

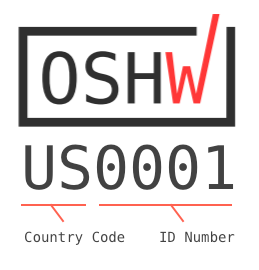

Read More...OSHWA Certification 2.0 is Here

This post originally appeared on the OSHWA blog.

Read More...Revoking Certification for ES000001 MOTEDIS XYZ

This post originally appeared on the OSHWA blog.

Read More...OSHWA Certification Logo is Official

This post originally appeared on the OSHWA blog.

Read More...Unlocking 3D Printer Hearing at the US Copyright Office

I originally wrote this post on April 14, immediately after the hearing it describes. At the time I assumed that the video of the proceeding would be released soon, so I held it in drafts until I could add the relevant videos. As it is now early July, I decided to post what I have as is. I’ll add the videos if/when the Copyright Office ever posts them.

Read More...