What does competition in the world of music look like without copyright? We may be on the cusp of finding out.

Read More...Which CERN Open Hardware License Should I Use?

Trying to decide which open hardware license to use? Not super interested in actually reading the text of licenses? You have come to the right place. There are a bunch of caveats at the bottom of this post, but let’s get to the heart of things.

Read More...Are AI Bots Knocking Cultural Heritage Offline?

Last week the GLAM-E Lab released a new report Are AI Bots Knocking Cultural Heritage Offline?. The short answer seems to be “yes”. The longer answer fills a report.

Read More...Does an AI Dataset of Openly Licensed Works Matter?

A team just announced the release of the Common Pile, a large dataset for training large language models (LLMs). Unlike other datasets, Common Pile is built exclusively on “openly licensed text.” On one hand, this is an interesting effort to build a new type of training dataset that illustrates how even the “easy” parts of this process are actually hard. On the other hand, I worry that some people read “openly licensed training dataset” as the equivalent of (or very close to) “LLM free of copyright issues.”

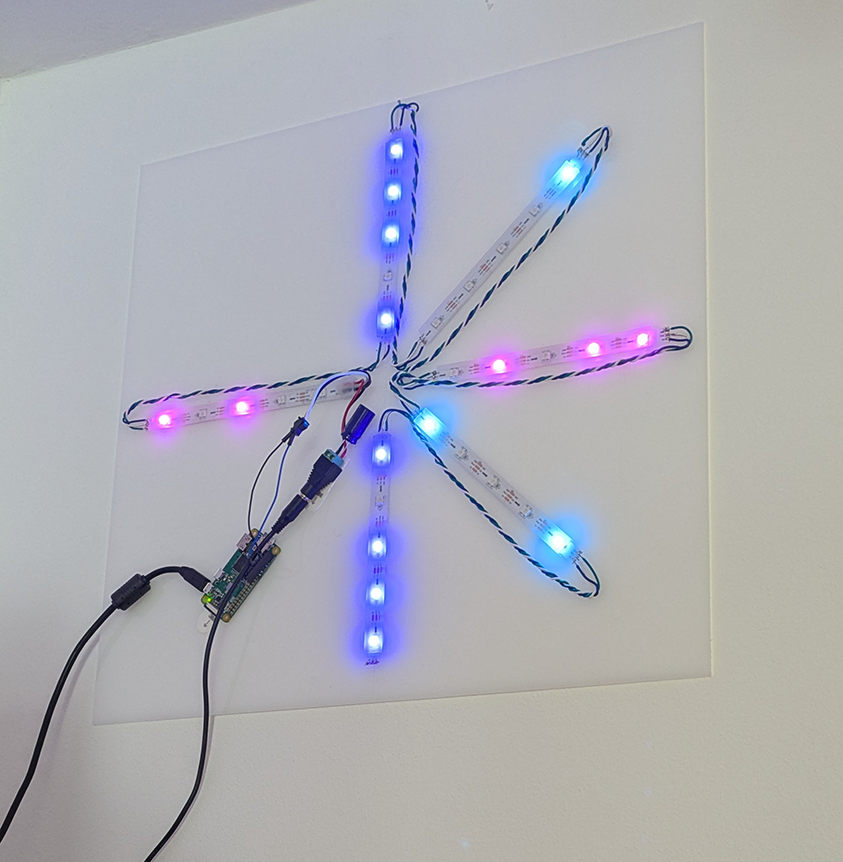

Read More...Pi-Powered Berlin BVG Alerts

Moving from NYC to Berlin gave me an excuse to update my old Pi-Powered MTA Subway Alerts project for the BVG. Now, as then, the goal of the project is to answer the question “if I leave my house now, how long will I have to wait for my subway train?”. Although, in this case, instead of just answering that question about the subway train, it also answers it for trams.

Read More...