This post originally appeared on the Shapeways blog.

Earlier this month I was lucky enough to present at the 2015 Creative Commons Global Summit on a question that I’ve been chewing on for the past few months: what is the proper way to give attribution to a designer of a 3D printed object?

First, some quick background. Creative Commons is the organization behind the Creative Commons (CC) licenses and logos. CC licenses give creators a way to contribute their copyright protected creations to the public, while at the same time conditioning that contribution on some straightforward terms. For example, CC BY-NCmeans that anyone can use the work in a noncommercial manner without additional permission from the creator as long as they give the original creator attribution (“CC” is Creative Commons, “BY” is attribution required, and “NC” is non-commercial use). CC BY-SA means that anyone can use the work as long as they give the original creator attribution (“BY”) and license any content the builds upon the work under the same license (“SA” or share alike). Credit is important to the CC ecosystem, which means understanding how to give credit is an important part of using CC licensed objects correctly.

The question of how to comply with these terms is important because not complying with a CC term means that you are infringing on the original creator’s copyright (for the purposes of this blog post, I’m ignoring the wealth of 3D printable models that are not protectable by copyright. If you are interested in exploring that line, this whitepaper may be a helpful place to start.)

For the original works that CC was primarily designed for, this attribution requirement was fairly straightforward (here’s the CC-maintained best practices for doing just that). If you use a CC-licensed image in a blog post, put a credit below the image or at the end of the post. If you use a CC-licensed song as the soundtrack to your video, add the credit at the end. In most of the digital world, there is often plenty of space for attribution metadata.

As is often the case, this relatively straightforward system gets a bit more complicated when it comes into the world of 3D printing. As long as we stay digital, adding attribution to a 3D file can be simple. Once that digital file becomes physical, attribution can get a lot harder.

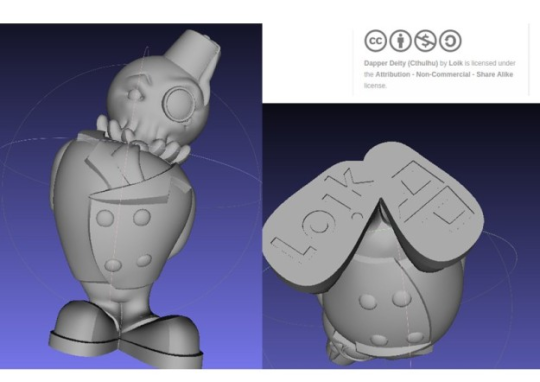

In some cases, that attribution takes care of itself because it is built into the model itself.

In the case of this model, the designer’s name is embedded in the bottom of the shoe.

Although even this is an imperfect solution. If someone decides to remix the model – something that is allowed under the license – and not take the feet in the process, that attribution disappears.

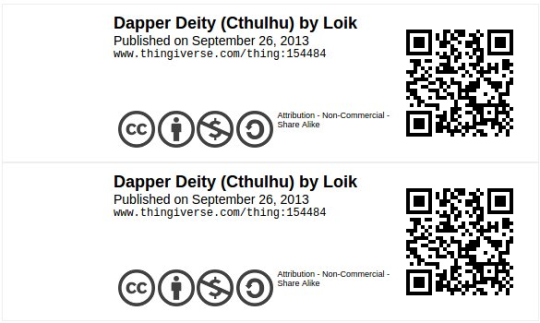

Most models don’t even start with attribution embedded in them. Thingiverse provides a solution in the form of a credit tag:

The credit tag can work in some situations, especially when you are displaying models in more formal settings like a gallery or trade show. However, there are still plenty of times when a tag just doesn’t make sense.

Take, for example, jewelry. When this designer CC licensed these earrings:

Or this designer CC licensed this bracelet:

Did they intend for the person who downloaded and printed the model to hang an extra tag off of them for attribution? Probably not. But what’s the alternative? Is it enough to tell people who ask where the pieces came from? I don’t know that anyone is sure.

The existence of this question is actually a testament to the success of Creative Commons, and to the way that the 3D design community has embraced CC licenses. CC has become so second nature to so many people that they don’t even feel the need to walk through each of the elements and spend time considering what they will mean in practice for a specific model. I’m guilty of the same thing myself.

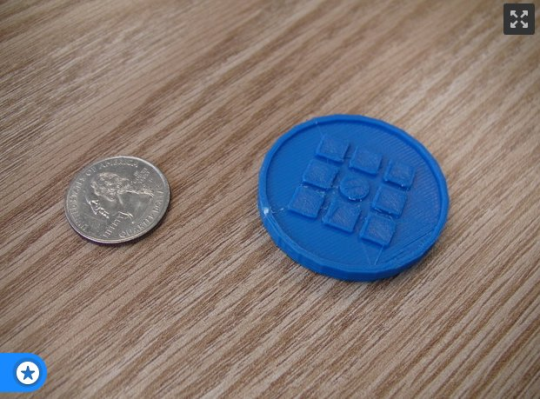

I released this coin with the logo of Public Knowledge under a CC BY license. What kind of attribution was I imagining? I have no idea.

So what is the best way to do attribution for 3D printed models? I do not have an answer to this question. It is fantastic that so many people have embraced CC licenses for 3D printable objects. Now it is time to start building a common set of expectations and best practices. There is no right or wrong answer. It would just be helpful to have an answer so people who want to comply with the wishes of a designer know what is expected of them.

That doesn’t start with me. That starts with you. If you create 3D printable models and license them under CC-BY, what do you expect? What does that BY mean to you? Let me know in the comments or on twitter@MWeinberg2D.

Read More...