NFTs are hot. OpenGLAM is hot. People have THOUGHTS and OPINIONS when NFTs and OpenGLAM get near each other.

Before spending any time discussing if NFTs and OpenGLAM should go together, it is worth considering if NFTs and OpenGLAM even can go together. Are they even conceptually compatible?

This question of compatibility between NFTs and OpenGLAM is a marginally interesting question on its face. It is an actually interesting question when used to illuminate an ongoing debate about the relationship between open collections and GLAM finances. This post is my attempt to do the second thing.

Here’s the short version: GLAM institutions should realize that NFT discussions are really discussions about leveraging the power of an institutional brand in an environment where the objects in the institution’s collection are ubiquitous. Regardless of how (or if) they decide to engage with NFTs themselves, those institutions can capitalize on NFT-spurred discussions to think more broadly about ways to move revenue generation models away from scarcity and towards ubiquity. That’s true even if the NFT discussions are only happening internally.

NFT Preamble I: Problems

This post begins, as any post about NFTs must at this point in the conversation, by recognizing the many problems that exist with NFTs today. These problems start with their truly horrifying environmental impact involved with the creation and transacting of NFTs (documented early, and I still think best, by Everest Pipkin here. One can debate as to whether or not this is strictly speaking an NFT problem or a blockchain (or a proof of work blockchain) problem, but NFTs are on a blockchain so for the purposes of this post that distinction doesn’t really matter).

The problems continue with the fact that it seems likely that the overwhelming majority of people involved in NFTs do not appear to fully realize what rights NFTs actually convey. That includes people who think that buying NFTs gives them some sort of ownership over the thing represented by the NFT, people who think selling an NFT for something you don’t own infringes on the owner of the thing’s rights, and people who think that buying an NFT in a thing gives you control over that thing beyond what you would have if you actually purchased the physical thing.

An additional set of problems emerge because the NFT market is frothy and unregulated. That makes it home to pretty much every flavor of financial scam yet conceived by humanity (we are in the ‘fraud is so widespread that content farms write articles about NFT scams’ phase of NFT evolution). Among other things, that means that pretty much any headline valuation of an NFT should be read with a degree of skepticism, and any new NFT scheme should be evaluated for potential scamminess.

Finally, the NFT space provides a place for people to waive away or just imagine their own set of legal and cultural rules. That happens with varying degrees of effectiveness and can actually end up being kind of useful in some cases, while being terrifying in others.

These problems emerge from the current incarnation of NFTs. NFTs may someday become more environmentally responsible, better understood by people involved in them, less scammy, and more tethered to reality. But that’s true of a lot of things. There is no law of gravity that demands that be so. And, as of now, the “claim to legitimacy” to “evidence of legitimacy” ratio for NFTs is still way out of whack.

To be clear, none of this means that the NFT space is completely devoid of interesting projects. It just means that they are fairly hard to find, and ones that I have found don’t really justify a multi-billion-dollar phenomenon.

NFT Preamble II: What They Are

There are a million explainers about NFTs on the internet. If you are reading this you already know the gist, so I’ll focus on the part that is important for this discussion. To the extent that you need more background, this article by Kal Raustiala and Chris Sprigman is great. This article by Foteini Valeonti et al is also helpful, and provides additional context for the GLAM space specifically.

For the purposes of this post, the most important thing about NFTs is that they do not claim any sort of ownership in the underlying thing represented in NFT, or assert a transfer of ownership of the underlying thing between the seller of the NFT and the buyer. That’s how Brian Frye, someone with a very nuanced understanding of the legal and conceptual aspects of NFTs, felt very comfortable selling an NFT of the Brooklyn Bridge, a piece of infrastructure that he certainly does not own. That’s also why it is not copyright infringement to sell an NFT of someone else’s art.

Instead, all an NFT claim is that someone wrote down that the original buyer was associated with a thing in a blockchain ledger. While NFTs can work conceptually even with a random person and a random ledger, in practice the economics of NFTs require that someone care enough about the combination of the original recorder and the ledger to pay for it.

OpenGLAM Preamble I: The Issue

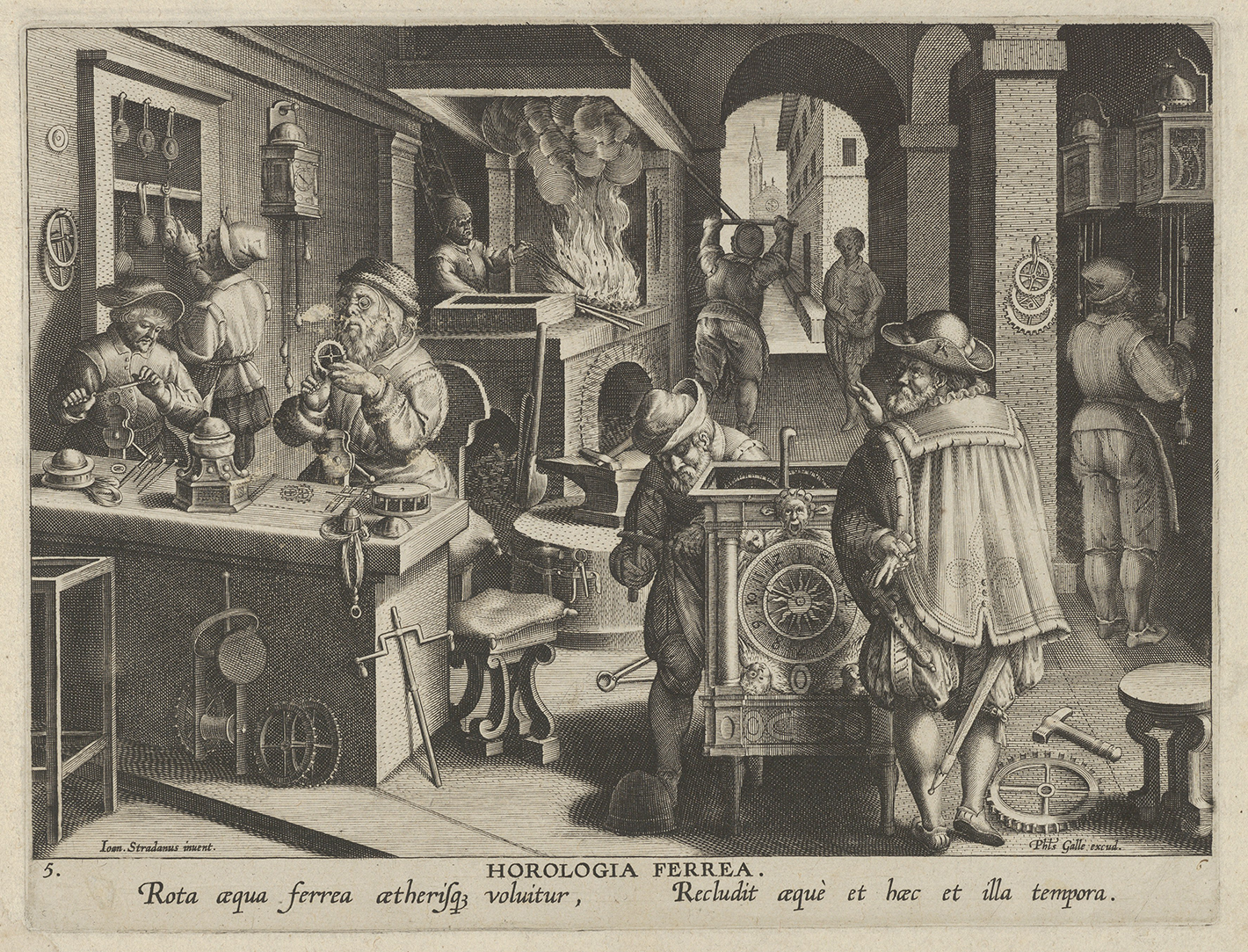

OpenGLAM (that’s Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) is a community of people, institutions, and practice working to make our common culture available to anyone, so they can use it anywhere, in a manner of their choosing. In practice this means focusing on digitizing public domain works and releasing those files under a CC0 public domain dedication.

Many of the institutions involved with, or considering getting involved in, the OpenGLAM movement had or have legacy rights and licensing departments. In a pre-OpenGLAM context, these departments sold licenses for various types of reproductions of works in their collections. That includes licenses for works that were themselves in the public domain. If you want or wanted a picture of a specific painting in your fancy art book or academic article, these are the people you pay to use the picture.

This kind of licensing model is built on exclusive control. The institution could charge for a license to use a picture of a 13th century painting because they were the only ones who had full access to it and were the only ones with control over a high-quality image of it. If everyone had access to the painting, or if the high-quality image of the painting was freely available for anyone to use, there would not be a reason to pay the museum to use it. (There actually are still reasons that you might want to pay the museum to use it, but that’s an issue for another post (or a bit later on in this post)).

This raises a question for institutions who are considering transitioning to an open model: what will going open mean for the revenue they traditionally drew from licensing?

Before connecting that question with NFTs - we’re getting there, I promise - I want to add three caveats to it:

Caveat 1: Most institutions draw relatively modest revenue from their licensing programs. When you factor in the costs of actually running these licensing departments, many of them may actually lose money.

Caveat 2: There is plenty of evidence that open strategies can be used to increase revenues.

Caveat 3: It is always reasonable to ask how institutions should think about balancing their need to pay for things with their mission (and social compact) to make their collections available to the public, and if licensing revenue should even be considered legitimate in the first place. Suffice it to say that this is a question upon which reasonable minds may disagree. More importantly for the purposes of this article, regardless of its conceptual legitimacy, it is a concern that institutions regularly express.

Enter NFTs

NFTs do have at least one interesting feature: they combine exclusivity with ubiquity. As discussed earlier, the NFT isn’t the thing it represents. The NFT is just someone writing down your name next to the name of the thing in a ledger. That means that what you are buying (being written down in the ledger) is not in inherent conflict with the thing your name is being written down next to being ubiquitous and freely available to everyone. The thing being available to everyone does not change the fact that your name was the one written down in the ledger.

The result is that, unlike selling licenses to use images, there is not an inherent conflict between selling an NFT and making the underlying work connected to the NFT freely available to anyone. OpenGLAM and NFTs are compatible, at least conceptually. Widespread, open access to the underlying thing does not directly impact the economic viability of the NFT.

Instead, in many ways, most of the value of the NFT comes from leveraging the reputation of the institution that is writing the buyer’s name down in the ledger next to the name of the work. An NFT of the Mona Lisa offered by the Louvre (that’s the Louvre writing your name down next to the Mona Lisa in the ledger) would probably be worth more than an NFT of the exact same Mona Lisa offered by me (that’s me writing your name down next to the Mona Lisa in the ledger).

Why the distinction? The NFT represents officially sanctioned affiliation with the work. That is different from ownership of the work or control over the work. Nonetheless, that officially sanctioned affiliation might be worth something to someone.

NFTs as Official Merch

Viewed this way, the NFT model is strikingly similar to an ‘official licensing’ strategy for open works. Under both models, everyone has full access and use of the open access work. Also under both models, some people can pay a fee to the institution for a more official affiliation.

For the NFT, that affiliation takes the form of a record in a ledger that documents that it was the institution that wrote your name down next to the name of the work. For the official licensing model, that might take the form of the right to use the institution’s trademarks with your product that incorporates works from the open collection, some sort of certification that the use or reproduction of the work is in line with curatorial standards, or something else.

Both of these models sell an institutional endorsement of the user’s affiliation with the work without limiting anyone else’s access to the work (although only the NFT comes with a frothy market and the ability to easily transfer that affiliation).

Is This a Good Idea?

Just because the idea of NFTs is compatible with the idea of OpenGLAM does not mean that OpenGLAM should embrace NFTs. It only means that OpenGLAM could embrace NFTs if it was so moved.

The start of the answer to the “is this a good idea?” question lies in NFT Preamble I above. There are major risks and costs that come with getting involved with NFTs as they currently exist. These include environmental costs, reputational costs, and other costs in between.

These costs are real and high. Even if the sale of some NFTs could finance the opening of an entire collection, the cost of doing so under current conditions could be very hard to defend.

Another part of this answer lies in the fact that institutions need to do real thinking about how and why they use their brand to validate affiliations. That is true in the NFT context, and in its activities more broadly.

At a minimum, without doing anything else, NFTs may act as a mechanism to allow institutions to think more creatively about what it means to capture value from their open collections. It makes it easier for people within those institutions to think more broadly about their brand association value, especially in connection with their open collections. If that happens it will be useful. Although maybe not useful enough to justify everything else.

Header image: Scene at a Fair: A Magician from the Met Open Access collection