3D printing was left out of the Undetectable Firearms Act, but the discussion about 3D printed guns raises broader concerns about how well lawmakers understand making things at home.

Yesterday the Senate passed an extension of theUndetectable Firearms Act. While this act is mostly about what its name suggests – undetectable firearms – discussion about the bill has managed to bring in 3D printing. As an organization, Public Knowledge takes no positions on gun policy. Therefore we would not normally have anything to say about a gun-related bill. But Public Knowledge is involved in 3D printing policy. With the passage of this extension in both the Senate and last week in the House, now is a good time to explain what has lead us to this point, what is happening now, and how it all impacts 3D printing.

What is this Undetectable Firearms Act?

The Undetectable Firearms Act is nothing new. It was first enacted in the late 1980s and has been reauthorized at fairly regular intervals ever since (the Act has a sunset clause built into it that schedules the Act to expire after a fixed amount of time if Congress does not reauthorize it). It was apparently originally motivated by concerns about all-plastic weapons that could pass through a metal detector (like at an airport) undetected by security.

The most recent version of the Act just so happened to be scheduled to expire yesterday.

Enter 3D Printing Guns

When stories about 3D printed guns first started popping up, many lawmakers felt compelled to respond. Those responses generally took two forms. One form was a concern that 3D printing could allow people to make guns at home. Once it became clear that people have been making guns at home for decades, and that existing gun regulation already accommodated this fact, this concern started to die down.

The other form was a concern about the undetectability of 3D printed firearms. While there aremetal 3D printed guns, many of the initial stories were about guns that were made with plastic. These 3D printed plastic guns, like any kind of plastic guns, were potentially undetectable by traditional metal detectors. Thus, they potentially raised the same security concerns that all plastic guns raise.

Representative Steve Israel was one of the first lawmakers to respond. His initial bill, which was designed to extend both the duration and scope of the Undetectable Firearms Act, focused heavily on 3D printing. Because of what we viewed as an unnecessary focus on 3D printing, Public Knowledge expressed concern about the bill.

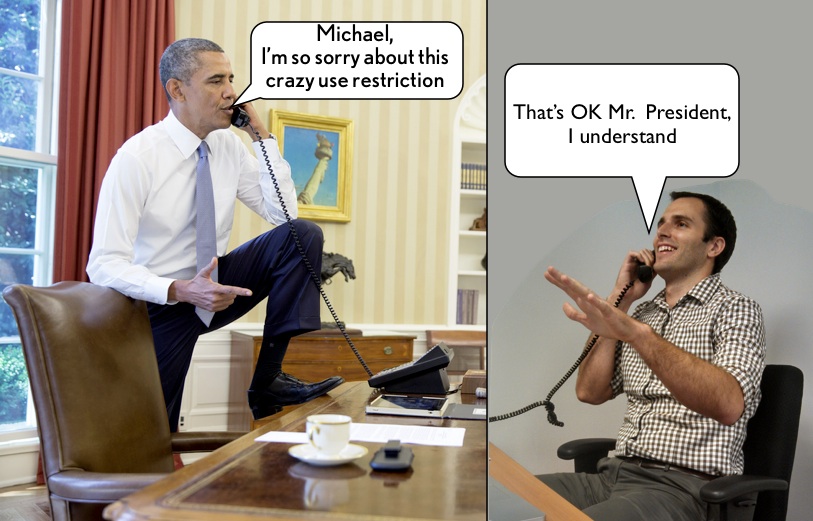

Fortunately, unlike other lawmakers who seem dedicated to a legislate first, think second approach, Rep. Israel was encouragingly receptive to our concerns.

Our primary request was that Rep. Israel focus the bill on the undetectability of firearms. Press coverage aside, the method of manufacture of an undetectable firearm should not particularly matter for undetectable firearm regulation. If a gun gets smuggled through airport security, it does not really matter how it was made. What matters is that it was undetectable, not that it was manufactured on a 3D printer, or a CNC machine, or with an injection molder. Public Knowledge takes no position on firearms regulation, so our only request is that any potential firearms regulation not unnecessarily undermine 3D printing.

Encouragingly, the revised version of Rep. Israel’s bill spends a lot less time talking about 3D printing and a lot more time talking about undetectable firearms. In addition to extending the prohibition on undetectable firearms, it focused primarily on including a requirement that any firearm feature at least one functional metal part (as opposed to simply include some detectable metal somewhere in the design). In the Senate, Senator Schumer has also been responsive to our concerns about the 3D printing element of this legislation.

The Most Recent Bills

With the expiration looming, last week the House moved to extend the term of the Undetectable Firearms Act. Instead of voting on Rep. Israel’s bill, it focused on a less contentious “clean” bill that simply extended the current law without substantively changing it. In good news for 3D printers, the current law does not include any references to 3D printing.

Yesterday, the Senate passed an identical “clean” extension. With passage in the House and Senate, President Obama signed the bill last night and extended the duration of the current, 3D printing free, version of the Undetectable Firearms Act.

Going Forward

With the extensions passed, the deadline pressure to pass a bill that expands the scope of the Act in addition to extending it has lightened somewhat. As such, it is unclear what will happen to the Israel bill in the House or the Schumer bill in the Senate. That being said, Public Knowledge does look forward to continuing to work with both Rep. Israel and Sen. Schumer to avoid unnecessarily drawing 3D printing into any gun legislation.

Perhaps more importantly, this entire episode highlights just how disconnected we as a society are from manufacturing and making things. 3D printing is an exciting technology that empowers people to make all sorts of things (not necessarily the “everything” that some lawmakers imagine, but plenty of things nonetheless). But it is not the only way that people can make things. Although it can often feel this way, not every object or device comes fully formed from a factory. People have had tools to make things on their own since the dawn of mankind, and many still have those tools at home today.

Many lawmakers responded to 3D printing as if it was the first time they had considered that it is possible for people to make anything on their own at home. Much of the discussion around 3D printed guns is a symptom of that shortsightedness. Unfortunately, it is unlikely to be the only one.

It is true that 3D printing will have new legal and policy implications that need to be addressed by lawmakers. But concern about simply “making things at home” cannot become a justification to cripple 3D printing – or any other maker technology – with regulation.

Read More...